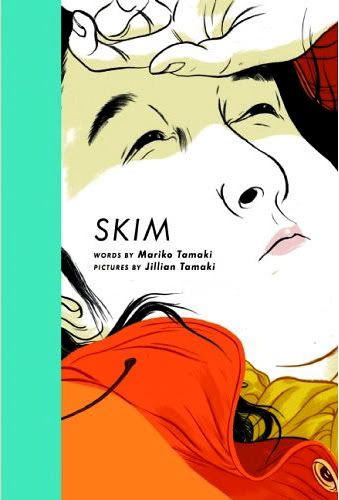

Skim

SkimWriter: Mariko Tamaki

Artist: Jillian Tamaki

Publisher: Groundwood Books

I wrote this last year, before Skim jumped onto all the "Best of 2008" lists. Well, at least one I know of. And it richly deserves its place there. I want to revisit it as I refocus this blog's direction.

Ahhh... the joys of being smart enough to see through the bullshit, but not so self-assured you can do anything about it or rise above.

It’s 1993, a Canadian suburb and Kimberly Keiko Cameron is 16 years old and depressed. Which- if I remember my own 16th year correctly- is almost a redundant statement. She's an alien among her peers and her friends and enemies at her all-girls school call her Skim because, as she explains, she’s not. Skim and her best friend Lisa are novice witches, and protect themselves (poorly) against the psychic bruising of high school life with pentacles, cynicism and sarcasm.

After a classmate’s boyfriend commits suicide, Skim finds herself under scrutiny as a “gothic” and an individualist. Almost everyone seems to think she’s next. Lisa expresses her contempt for the whole affair and everyone involved, while others opportunistically try to pad their school resumes and no one seems to care how the girl involved feels about this outpouring of well-intentioned but partially sham sympathy.

Skim herself has more on her mind than suicide and the sympathy fads of the herd-minded. She’s become interested in Ms. Archer, the exciting, free-flowing English teacher who tells her she has the eyes of a fortune-teller and fires her imagination.

Mariko Tamaki limns a first person narrative through Skim’s diary entries as the whole mixed-up drama unfolds. She presents Skim as a fully-realized protagonist, an introspective, occasionally self-doubting yet incredibly intelligent and perceptive young woman. Mariko handles this narration with skill, especially in scenes where Skim’s diary entries provide ironic counterpoint to the on-panel action. Early in the story, Lisa asks Skim how she broke her arm. “I fell off my bike,” Skim replies.

The truth? She tripped on her Wiccan altar and fell on her mom’s candelabra.

Throughout Skim, Mariko explores the myriad ways life's dumb realities confound our expectations, even if they're less than grandiose. It's not just that people say one thing and do another. It's also that it's tough to take photos of the cast on your right hand with your left when you're right-handed, just as difficult to illustrate broken-heartedness on the backs of your hands for similar reasons. Skim's first coven doubles as an AA group. Friends disappoint, parents fall out of love, the people we love prove to have their own agendas and leave us wanting our tarot cards back.

Skim may be down, she may be overly critical of herself and her classmates, but she's a thoughtful, intriguing human being, able to accurately question the motives of others even while her own judgment is somewhat clouded by her burgeoning teacher-crush, which plays out with an intensity that any of us who has ever loved someone too much will recognize (and perhaps feel thankful we've outgrown... hopefully). Despite granting her protagonist self-awareness, Mariko Tamaki never lets Skim become preternaturally wise beyond her years. Instead, Skim's narrative voice remains that of a believably bright teen, still unformed. Her dialogue and diary entries ring true. In fact, the dialogue throughout is fresh and naturalistic and Mariko shows a keen ear for the way teens and adults alike talk, think and express themselves.

At the same time, Skim’s something of an iconoclast as she demonstrates with a startlingly reductive view of Romeo and Juliet. This is in contrast with her pal Lisa, who talks independence and free thought but seems to constantly court acceptance.

In a hilarious scene, Lisa has talked Skim into accepting a double date with a couple of private school boys who appear dressed in their school uniforms and show nothing but contempt for Skim’s Shakespearean critique. Revealingly, their own view is informed solely by conventional wisdom and it's doubtful they’ve even read the play themselves.

Mariko’s cousin Jillian defines Skim’s world with loopy, swooping lines that give the illusion of movement, with furry drybrush and areas of deep black, plus lots of well-placed gray tones. Her storytelling is superb. This is a book of deeply felt emotions, of quiet moments, of conversations and silences. Jillian frequently looks away from the characters to focus on the minute, mundane yet keenly observed details of their surroundings in fragmentary still lifes, all those mood-building aspects. Jillian's figure work is gestural, active and energetic and she has an almost superhuman ability to find visual poetry in commonplace activities. Watch Skim’s mom crack pasta in half while making dinner, see the girls light cigarettes, argue in the bathroom or gleefully dance when cracking themselves up with the cruel humor of too-smart-for-their-own-good teenagers.

When was the last time you saw a comic book character twist open an Oreo to lick the cream filling? Jillian makes sure Skim moves and emotes in a distinctly different way than Lisa, than her mom. Each character is individualized and completely thought-through.

There are also single page images and double page spreads that freeze important moments- such as a momentous kiss- or else express narrative themes subjectively. Skim and Lisa attempt to invoke the spirit of the dead boy. They appear in silhouette on the spread’s lower right corner while trees created with bold brush strokes loom over them, a ghostly figure sitting on the left. Jillian uses more gray tones to give the illusion of depth, but also to give the scene a haunting, dreamlike quality. One of my favorite pages has Skim stomping out "I HATE EVERYTHING" in the snow after a false start. Another freezes a sequence of events involving a gaggle of ballerinas tossing a young Skim (dressed at the Cowardly Lion from The Wizard of Oz) and another girl (a soldier) out the door of a costume birthday party.

Skim's bitterly funny retrospective insight:

After a little while, Hien left. Hien's parents adopted her from Vietnam two years earlier and she never got invited to parties. Maybe she thought that's how people left parties in Canada. Asians first.

The cousins also deftly recreate 1993 with small details without allowing the book to become a nostalgia piece. Skim remembers giving a U2 tape as a birthday gift to the lead ballerina, her mother makes it a point to watch the TV show Sisters, and Skim dons a Nine Inch Nails t-shirt to attend the coven/AA meeting. There’s even a mocking reference to a guy with “80’s rocker hair and a turtleneck,” one of those style straggling holdovers from the previous decade. The concept of goth is so new, no one even knows what to call it. It's almost quaint to recall a time when we were more concerned about high schoolers harming themselves rather than massacring their peers.

Skim is an affecting, assured and impressive literary effort that doesn’t make me feel like an asshole for calling it a “graphic novel,” as well as a gorgeous hardcover full of lush art. It's my early pick for best of the year, but to be honest I don't know how many other graphic novels I'll actually read that aren't just collections of monthly books. I doubt any of those will sate the hunger for quality fiction about human beings and the amusing ways life disappoints and thrills the way Skim does.

No comments:

Post a Comment