|

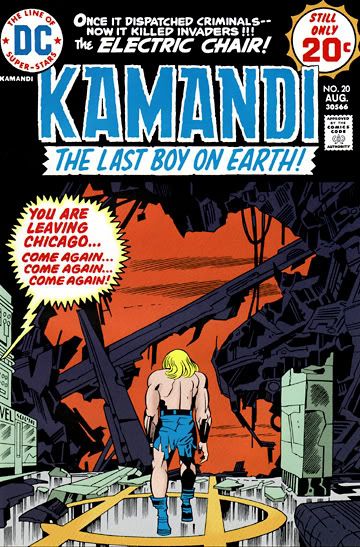

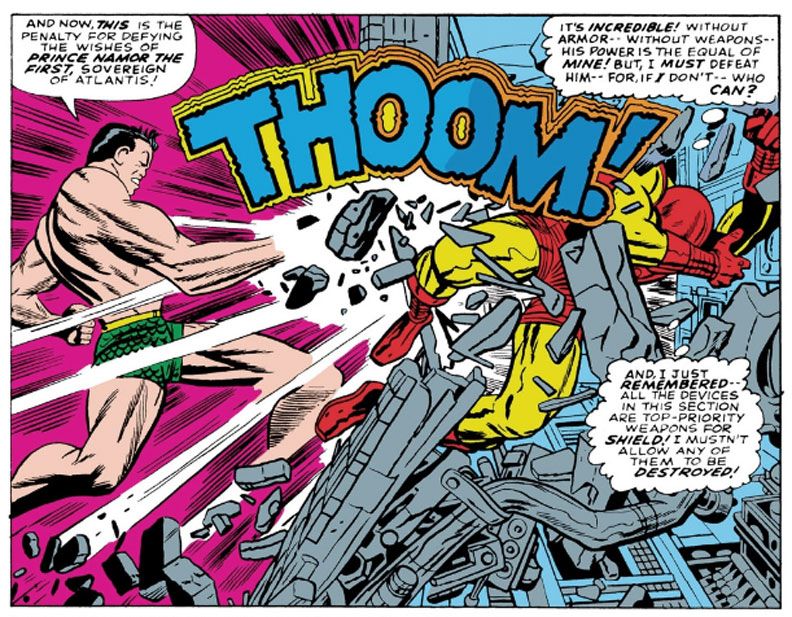

| Joe Kubert, August 1974 |

Memory. Unless you have eidetic memory, don't trust yours, especially when it comes to tracing formative events from your early childhood. This week I started thinking back to the first comic I could remember owning and once I started doing a little digging both in my brain and online, I came to a conclusion that's shaken my understanding of myself as a lifelong comic book fan.

For years, I've had this persistent memory I learned to read from DC's

Our Army at War #271, a book with art by the incomparable Russ Heath and a story by the inimitable Robert Kanigher. In the autobiographical film I constantly project in my mind, DC published it when I was three or four and there, on its pages, heretofore ignored ink marks inside the balloons coalesced into words, which formed into sentences and from there, the world of literacy opened to me. Then I looked

Our Army at War #271 up online and learned it has a cover date of August 1974, a mere month before I started first grade. I was already six years old, and, according to family lore, I had already been reading for quite a while at that point.

So maybe Robert Kanigher didn't teach me mah letters, but I thought there was still a decent chance his story "Brittle Harvest," the book's Sgt. Rock-starring lead, truly was the first bit of fiction I read that didn't star a persistent weirdo with a fixation on oddly-colored breakfast foods.

But maybe it wasn't...

|

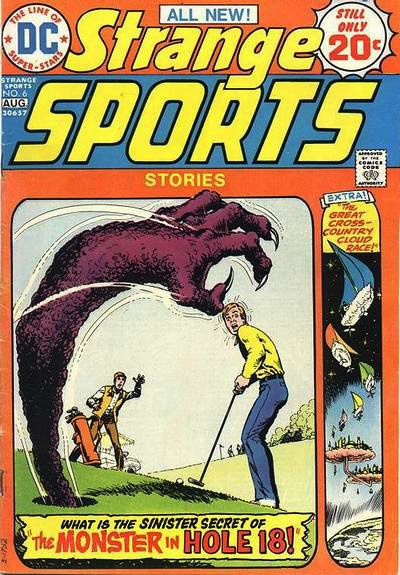

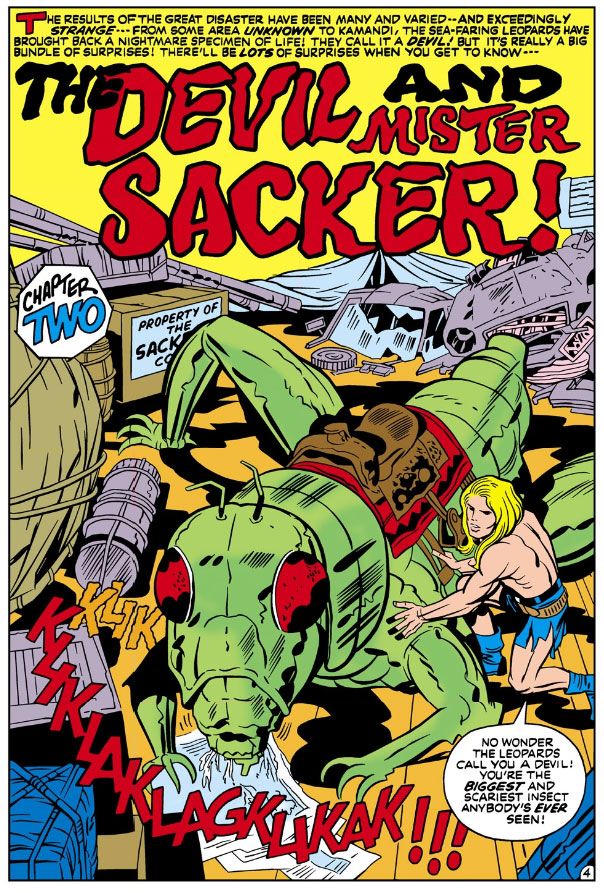

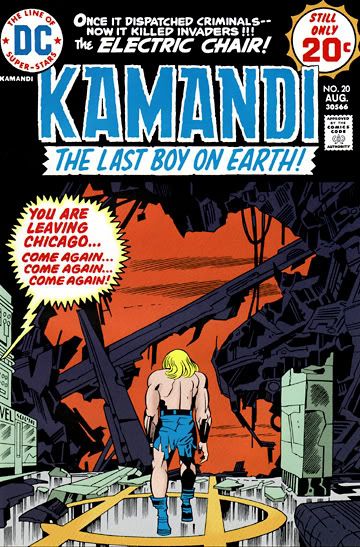

| Jack Kirby/D. Bruce Berry, August 1974 |

Because I also owned

Kamandi #20 and

Strange Sports Stories #6. I could have sworn both of those came out a year or two later. This week, I discovered DC published them that very same August. August 1974 was a good month for me as far as comics go.

How did I manage to obtain three comics when my income consisted entirely of spare change I found under the sofa cushions or dove for in the deep end of the local Elks' Club pool? Gifts, maybe. I can't imagine what fool would give me three comics at the same time. One, yeah. Two is stretching it. Three invites rumors of decadence, of profligate spending on a scale unheard of in our little clan during the Ford administration days of energy crisis and Whip Inflation Now.

Or else I somehow managed to collect enough pennies to buy them myself. Yet, I have trouble imagining any scenario involving either of my parents allowing me such an extravagance. Again, one comic, maybe two if I'd been especially well-behaved. Three would be, in my mom's words when I bought a second aluminum baseball bat during my "athletic" period years later when I actually had a job and income of my own, "Ostentatious." My parents, both products of hardscrabble Depression-era childhoods, instilled in me a financial caution I maintain even now that I'm as rich as the guy on the Monopoly game box. Even with their permission, buying three comics at the same time back then would have given me the same guilty feelings I get now whenever I pick up a new Rolls or sports franchise.

Whether from false memories of learning to read or from inspiring a lifelong love of Jack Kirby's work, each of these comics has stuck with me in ways I've learned are as foggy and treacherous as some jagged coast in an old sea story. I once again own both

Our Army at War and

Kamandi, so I've read them recently. In this way I've corrected a number of misconceptions I carried for years about their stories.

A physical copy of

Strange Sports Stories, on the other hand

, remains elusive and, therefore, its contents a jumbled mishmash of mistaken impressions.

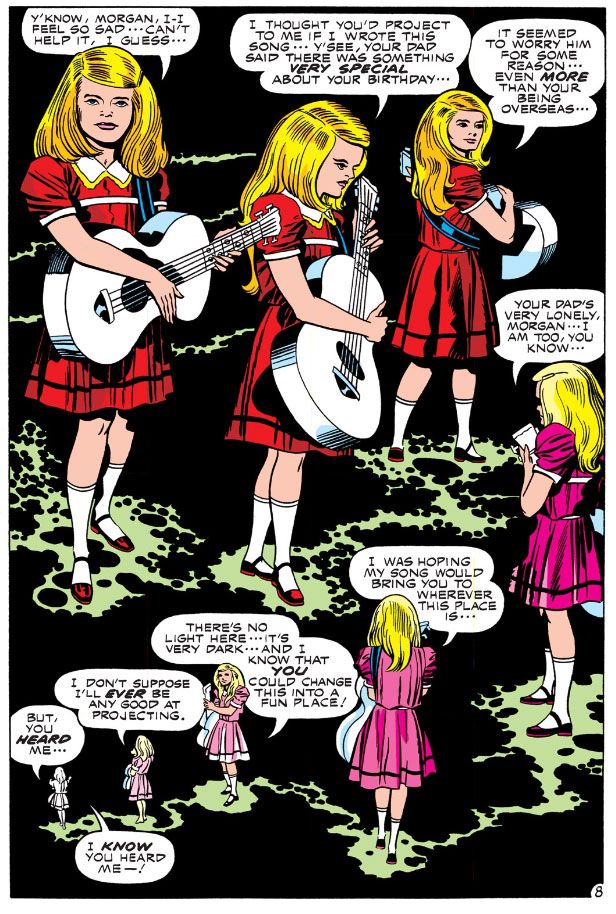

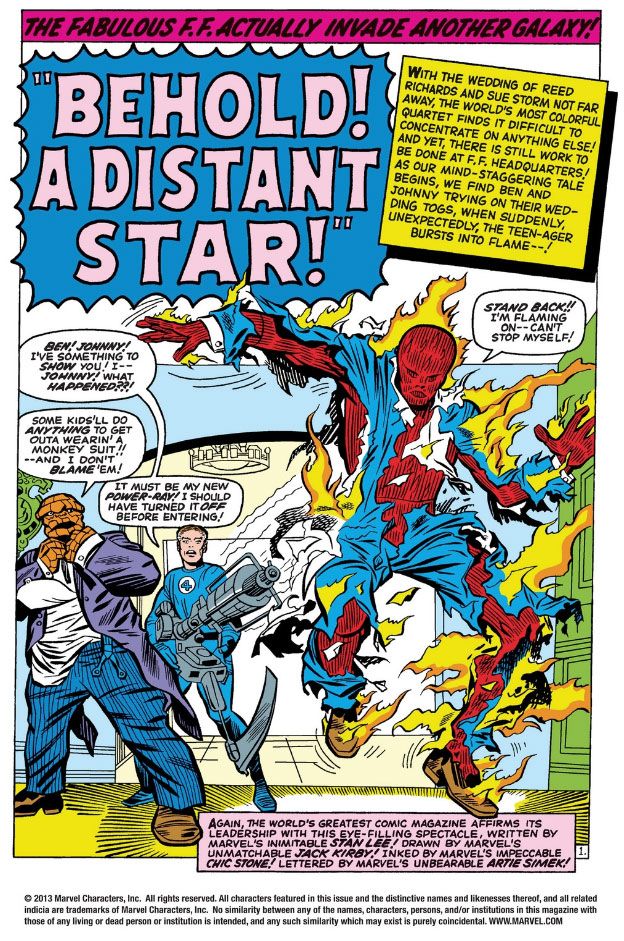

The cover is easy to find online, though. Let's take a look and see what recollections it inspires. Wow! It's by Nick Cardy! What a treat! I've really underestimated myself all these years. Kid me really had good taste in cover artists.

|

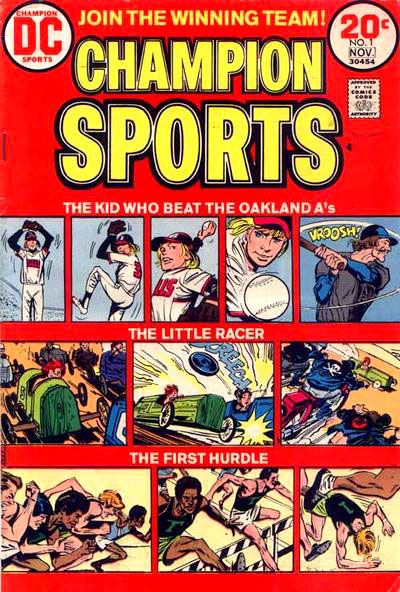

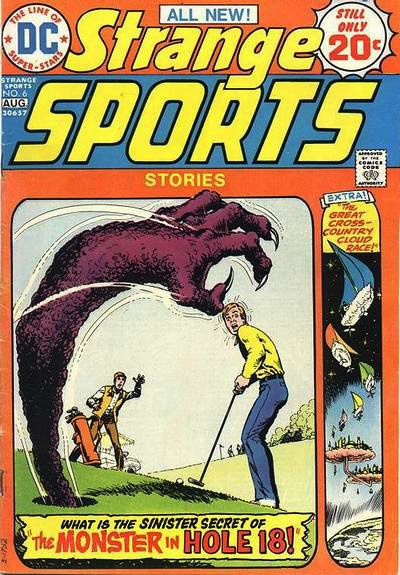

| Nick Cardy, August 1974 |

Let's look at the cover copy. Interesting story titles. I thought so at the time, but I may have been alone there, since this was actually the final book in the series. Another one of those failed DC experiments.

"The Monster in Hole 18!" inspires a vision of someone being pulled through the hole into an alternate dimension, his body grotesquely thinned and stretched in the process, leaving his midsection resembling a great noodle. At least during the transition. I'm pretty sure he came out the other side in whatever state for him passes as normal.

I may be conflating this with the events of "The Great Cross-Country Cloud Race," which I believe is about a couple of young guys seriously into boating who travel into another universe where people race through the skies in little sailboats made from solidified clouds. Perhaps these guys were the ones who went through a physically distorting transportation process of some kind.

The cover suggests the book contains just two stories. So why do I feel so strongly there was a third? One about a young guy who injures his arm in such a way he can throw baseballs at ridiculous velocity, gets signed by a major league team and pitches in a game against a New York Yankees-type powerhouse club before crashing his expensive sports car and losing his magical pitching ability when the doctor re-sets his arm. The same accident injures his hip, and there's a little matter of drop-kicking a football...

|

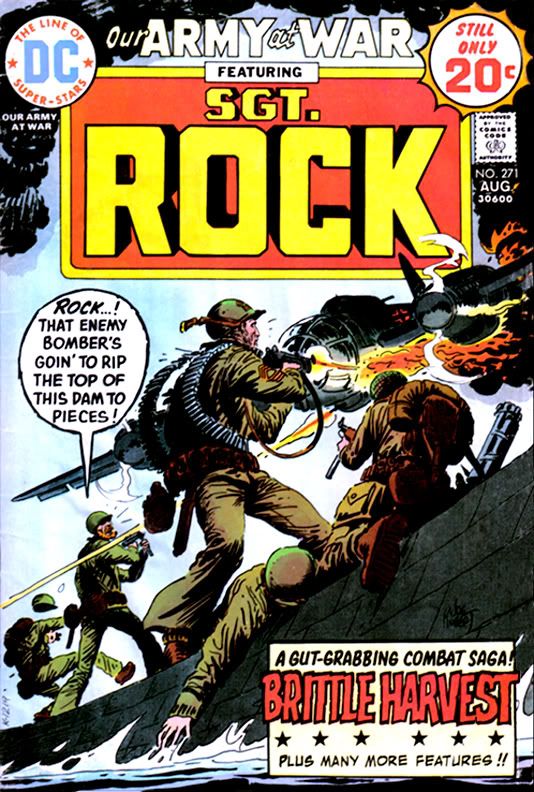

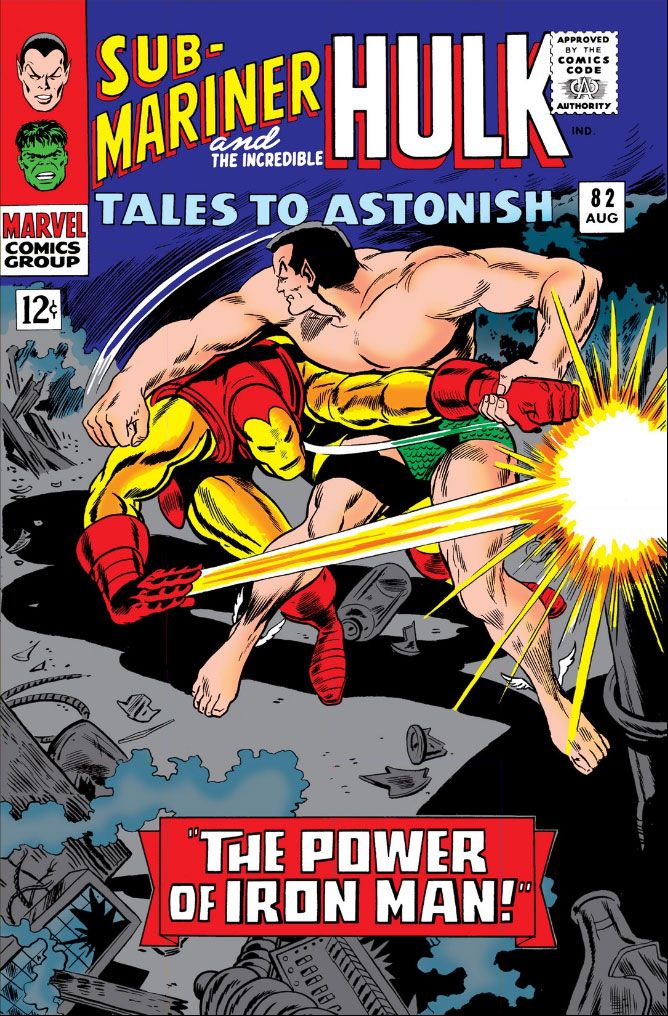

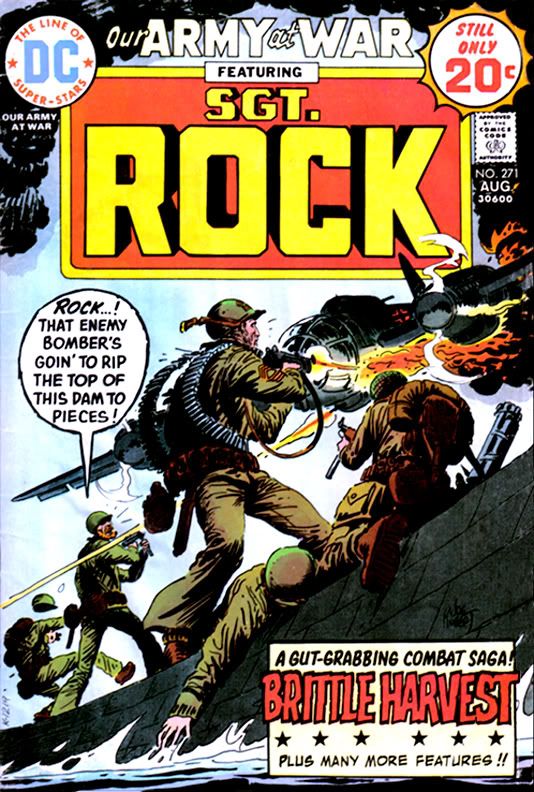

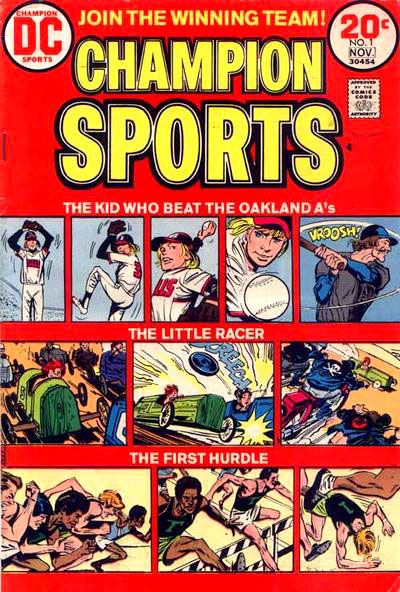

| Jerry Grandenetti/Creig Flessel, July 1973 |

Let me see what I can find out about this. Hey! It turns out there is such a story, but it isn't in

Strange Sports Stories #6. We find it instead in

Champion Sports #1.

And it isn't the New York Yankees he pitches against and wins. It's the Oakland A's.

That brings back a whole lot of memories! The A's of the early 1970s featured a potent line-up centered around a hard-slugging clean-up hitter by the name of Reggie Jackson, and a pitching rotation starring Vida Blue, Ken Holtzman and Catfish Hunter (Rollie Fingers was on the team, too), each of whom won 20 or more games in 1973. They beat the New York Mets in the World Series that year.

My family hated those guys and their evil mustaches because we were National League fans and my oldest brother, a catcher himself, idolized Johnny Bench. This meant we were Cincinnati Reds boosters, and they lost in the Series to the A's the previous year. It didn't matter that my uncle had caught for the A's when they were the Kansas City Athletics and personally knew and greatly respected Hunter.

So, in fact, the story is called "The Kid Who Beat the Oakland A's," and I've just learned it's written by the great Joe Simon, drawn by the nifty Jerry Grandenetti, with inks by Creig Flessel.

And

you can read it in all its glory on Diversions of the Groovy Kind, a super-cool website that's one of my favorites. The Groovy Agent must be one of those people with eidetic memory. He knows it all, baby. He took the comic's tag line to heart and joined the winning team!

The "kid" is David Wexler, a would-be writer and sports nut. He ends up enjoying a brief career in the Major Leagues, not as stellar as Catfish Hunter's or Vida Blue's, but still something to be proud of, especially the climactic event, which is spoiled by the title. The most telling detail, though, is the caption towards the end, when the kid's swelled head leads to his comeuppance: "You may have read about that game... What you didn't hear about was the dumb, wild things I did off the diamond." It's a single sentence Simon uses to introduce the off-the-field aspect of big time sports, and gives the story a gritty background verisimilitude to help put across its rather improbable premise. Shades of Jim Bouton's

Ball Four (1970) and the stuff the newspapers didn't print about Mickey Mantle.

Which reminds me! I could tell you a rather funny story involving my dad, my uncles, Mantle and Joe Pepitone down at spring training in Florida. Maybe one day I will, but for now let me just tell you my dad swore me to secrecy and I've already told you too much.

What about the other stories? Well, "The Little Racer" is about a soapbox derby kid who gets run over by a one-percenter motorcycle gang who then help him rebuild his racer with stolen parts. He ends up with quite a hotrod, but his innate honesty causes him to revert back to his green wooden crate for the final race, which he loses but fairly and squarely. Then the cycle dudes stomp him good, the same way the Hell's Angels did Hunter S. Thompson when they learned they weren't getting any of the money from the book he wrote about them. Okay, I made that last one up. The story thing, not the Hunter S. Thompson thing, which really happened. The comic may or may not have a happier ending. But even though our theme today is how crappy my memory is, I feel confident about its other details.

On the other hand, "The Last Hurdle" brings absolutely nothing to mind. I'm guessing it has to do with at least one hurdle. Perhaps a final one of some kind. Literal? Symbolic? Shambolic?

No, that's this blog.

This has been a day for shocking revelations, hasn't it? Let's conclude this mess with two more.

First, in December of 1997, the FBI investigated the possible theft of the artwork from this very comic, along with hundreds or even thousands of other pages. The entire sequence of events found near the bottom of the document makes for some interesting (if difficult due to formatting and spelling errors) reading. My oh my! The things you uncover when you take a memory trip. I'm completely flabbergasted.

And second, the answer to that nagging question that provides this post's title.

Champion Sports #1. Look at this: it has cover date of November 1973, same year the A's won their second World Series. Diversions of the Groovy Kind puts its actual release date as July, which means, depending on their own street dates, it hit the stands more than a year earlier than

Our Army at War #271,

Kamandi #20 or

Strange Sports Stories #6.

Champion Sports #1. I was five years old when I read it. It's now the earliest comic I can remember owning!