As I got older, I became enamored of Japanese noise rock and street fashion, cinema and subcultures. I'd be lying, however, if I said in all of that I didn't find some inspiration from American comics and depictions of Japan found in them. These were and remain heavily reliant on Clavell-esque storylines of Westerners getting deeply involved with modern-day samurai, ninja or, in a more recent switch, yakuza gangsters seemingly born from both Michael Crichton's anti-Japanese paranoia-laced Rising Sun and Kitano Takeshi's ultra-violent films, among others-- the yakuza film is a longterm genre in Japan, just as gangster films have been in America for decades. Lots of arrogant, angry, high-strung characters like Silver Samurai, Katana, the female Dr. Light and occasional X-Men ally Sunfire, references to revered ancestors and "losing face" and "retaining honor" and life debts and all that junk...

Well, the chances of encountering genuine ninja in contemporary Japan are just about nil, and meeting up with yakuza thugs with ancestral castles only slightly more likely. But if the storylines are somewhat ridiculous, how do their visuals match up to the real thing? Let's take a look at some carefully selected examples. It's by no means a comprehensive overview because it consists only of comics I've actually read.

First up is the Chris Claremont-scripted, John Byrne-illustrated The Uncanny X-Men #118, "The Submergence of Japan." In this story, the X-people have escaped the Savage Land and traveled by the research ship Jinguichi Maru to Japan, where they find the ship's "home port of Agarashima," a fictional seaport ablaze in a fire so hot they can feel it from "ten kilometers from shore." Byrne treats us to an epic double-page splash with our heroes in the foreground, a backdrop of the devastated cityscape spewing massive, lurid red flames and billowing smoke, Air Self-Defense Force fighter jets streaking overhead and with a snow-covered Mt. Fuji off in the distance, as if gazing impassively at the destruction. The buildings are a little exotic-shaped, but it does give one a feeling of place; Agarashima, if it existed, would probably be somewhere on the southern coast of Honshu, somewhere between Shizuoka prefecture and Tokyo, an area where there are plenty of coastal cities hugged to the Pacific by mountains.

Coming ashore, the X-Men make their way through the ruins. Neither Claremont's narrative captions nor Byrne's art dwell much on travelogue, so we miss a chance to see if Byrne can match his ultra-detailed North American settings-- that counterfeiting of reality that adds so much verisimilitude to the X-Men's superheroic antics during this classic period-- with some postcard-perfect Japanese backgrounds, albeit ones crumbled by an earthquake. Byrne gives us just enough to make the setting at least seem real:

The story quickly replaces modern Japan with more James Clavell-style fantasies, and Byrne deftly draws all the shoji (paper sliding door) and wooden walkways you could desire in a comic book story before he and Claremont send their protagonists off to some secret island base to fight Moses Magnum, a nut who wants to sink Japan. Interestingly, this idea of Japan's submergence has been a theme in Japanese science fiction literature. Magnum's hideaway is right out of the 1967 James Bond adventure You Only Live Twice, also set in Japan and the poster for which carries Western sexual fetishization of subservient Japanese women to ludicrous extreme.

The story quickly replaces modern Japan with more James Clavell-style fantasies, and Byrne deftly draws all the shoji (paper sliding door) and wooden walkways you could desire in a comic book story before he and Claremont send their protagonists off to some secret island base to fight Moses Magnum, a nut who wants to sink Japan. Interestingly, this idea of Japan's submergence has been a theme in Japanese science fiction literature. Magnum's hideaway is right out of the 1967 James Bond adventure You Only Live Twice, also set in Japan and the poster for which carries Western sexual fetishization of subservient Japanese women to ludicrous extreme.Sorry... I digress...

Even in such a fast-paced story, Wolverine finds time to meet and begin wooing a character who would become intrinsically linked with him, at least throughout the 1980s, Lady Mariko Yashida. He even presents her with a chrysanthemum and displays a heretofore unknown ability to speak perfectly fluent Japanese!

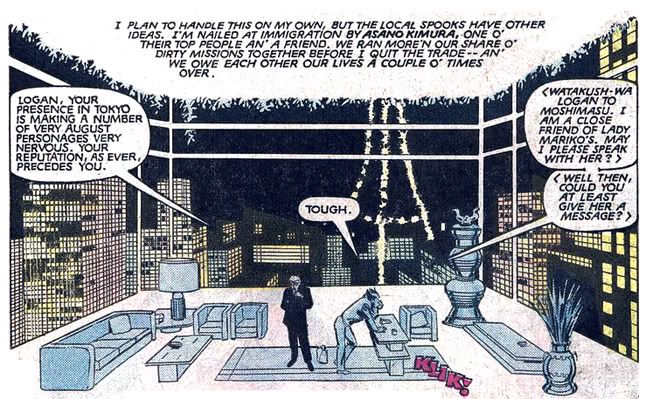

In the 1982 Wolverine miniseries, Claremont teams up with the artist most known in America for the influence of Japanese comics and cinema on his stories, Frank Miller. Together, they send Wolverine on a very Bond-like adventure in a modern day Japan practically overrun by crazed ninja assassins. This story is like a compendium of the American popular mythologizing of Japanese culture-- all samurai honor and Asian exoticism but set against the sleek electric cityscapes of the late 20th century. Clavell meets William Gibson, with Sonny Chiba as interlocutor.

In this image, Wolverine has checked into either an upscale apartment or the fanciest hotel on earth. It appears to be in Minato ward, because that's Tokyo Tower in the background. Minato is home to Roppongi and Roppongi Hills and in places is pretty much the skyscraper forest Miller illustrates here. Later, Wolverine finds himself drunk in an "alley off the Ginza." Ginza is a shopping district within the Chuo ward. I've never heard it referred to as "the Ginza," but who knows?

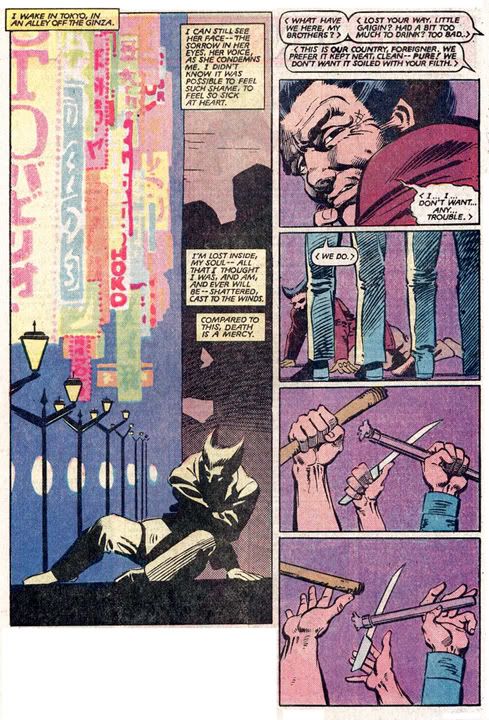

While I'm doubtful about the presence of anti-foreigner thugs in that particular area of Tokyo, again Miller's backgrounds prove surprisingly accurate:

While I'm doubtful about the presence of anti-foreigner thugs in that particular area of Tokyo, again Miller's backgrounds prove surprisingly accurate:

Not too shabby, eh? He even appears to have gotten the streetlamps correct. Still, I think if Wolverine were really looking to get his drunk on in a seedy part of Tokyo, he would have been better off hitting Kabuki-cho in Shinjuku. Ginza features its share of hostess bars, but is a bit more upscale and pricey. Kabuki-cho is often referred to by my students and friends here as the "most dangerous place in Japan." It's a down-and-dirty fun zone where at night you can see prostitutes, street-level yakuza, Nigerian gangsters and perhaps even members of Chinese tongs if you're lucky. They'll be mixed in with lots of businesspeople doing the after-work drinking thing and young couples in search of exciting nightlife so you may not even notice them. Sounds more like a Wolverine kind of place.

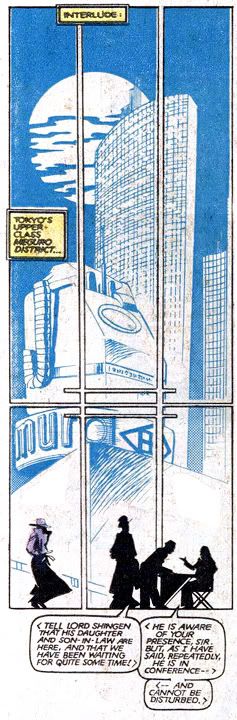

This is interesting:

As Claremont describes it in the caption, Meguro is indeed an "upper class" area. A number of celebrities make their homes there. What you need to remember, however, is the phone-shaped building. It will become important later.

As Claremont describes it in the caption, Meguro is indeed an "upper class" area. A number of celebrities make their homes there. What you need to remember, however, is the phone-shaped building. It will become important later.The story's climax and closing actions take place within the castle-like Yashida family "ancestral stronghold." Miller's architecture even more accurate here, but given the unfortunate destruction of most castles during the Meiji Period and flattening of Japan's major cities during WWII, it's pretty unlikely any private family would be living in something so... historical. In comic books as in life, sometimes coolness must trump accuracy. Would you want to read a story where a vengeful Wolverine scales the less-than-impressive walls of a fancy apartment building?

Perhaps, but Wolverine in a Edo-style castle is a bit more visually compelling.

The 1980s were prime time for Japanese influences in American pop culture. The decade began with the hugely successful TV miniseries adaptation of Clavell's Shogun and the major failure of Pink Lady and Jeff, a bizarre yet energetic attempt to make two talented J-Pop singers variety stars in the States. Later American television audiences would pretty much ignore The Master, an absolute bullshit adventure TV series starring Lee Van Cleef as a blue-eyed ninja; it would last a mere thirteen episodes and become Mystery Science Theatre 3000 fodder. This probably says as much about Western cultural misappropriation as having Canadian-born Wolverine described as "more truly Japanese than any Westerner I have ever known" by one of his allies. At least Claremont qualifies it somewhat. Wolverine can master the language and cultural mores, defeat the yakuza boss and win the hand of the nigh-unreachable Lady Mariko, but as a mutant as well as gaijin, he remains an outsider in Japan as well as in the West. Lee Van Cleef bests even the Japanese at their own martial arts, then walks away for personal reasons.

But I digress yet again...

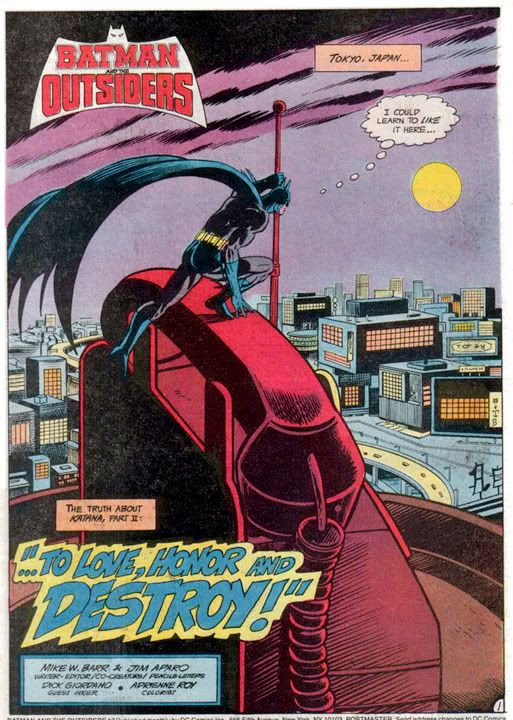

Perhaps inspired by Wolverine's Japan sojourn, Batman would take his Outsiders to Tokyo in 1984's Batman and the Outsiders #11. In this story writer Mike W. Barr and penciller Jim Aparo tackle the increasingly cliche story themes of the Japanese concept of honor and family loyalty as native-born Japanese Katana (described the following issue as the "She-Samurai") confronts her past and we learn all about her magical sword. The story is heavy on the ninja tropes but how do Aparo's Tokyo cityscapes fare as accurate depictions of that particular megalopolis?

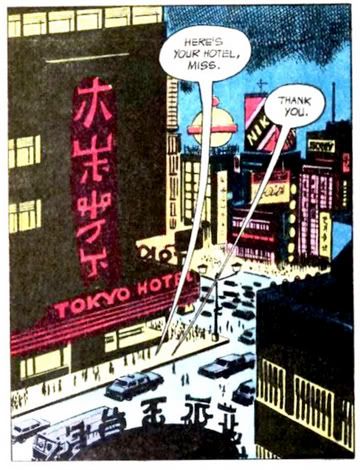

Not too badly, if this image is any clue:

He gets the omnipresent advertising signs correct. Many buildings here do feature giant signage on their rooftops and various kanji and katakana or hiragana running down their sides. This particular panel is somewhat reminiscent of the Kabuki-cho side of Shinjuku Station, although there's no "Tokyo Hotel" in the station, and there'd be a small plaza to the right instead of what appears to be a parking lot of some kind. Those types of lots are extremely rare here in land-starved Japan; more likely would be a high-rise parking deck looking like a big steel Rubik's Cube, but not nearly so colorful.

And again:

I have no idea if there is now or if there ever was a building with a gigantic telephone on top, but Frank Miller and Jim Aparo seem to insist upon its existence. Maybe it was a famous landmark of the 1970s and 1980s and both artists saw it on some kind of comic book publicity junket here. Or else Aparo is paying homage to the work Miller did with Chris Claremont. Since this story hits some of the same cultural notes, that's a distinct possibility. Aparo's buildings are a far cry from the Meguro seen in Wolverine, though. This looks more industrial (and generic) than "upper class," so perhaps the phone building is merely a fantasy.

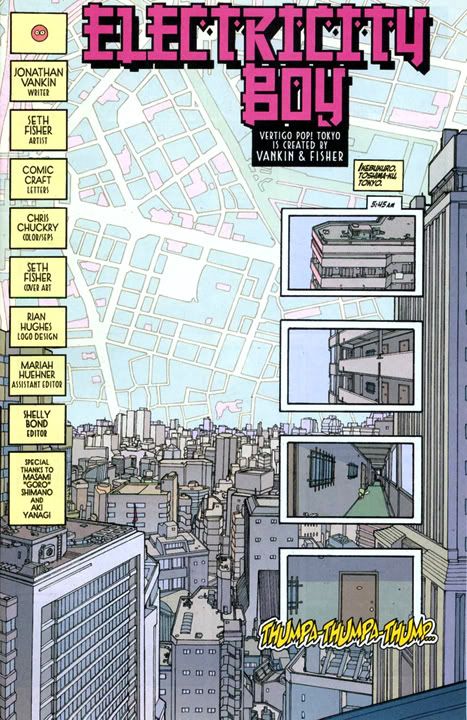

A more recent comic book look at Tokyo comes courtesy Vertigo Pop: Tokyo! by Jonathan Vankin and Seth Fisher. Vankin's story is another "Japan-as-other" fantasia, this time seen not through the eyes of superheroic adventurers but those of an ordinary American electronics geek. To that end, Vankin's protagonist is somewhat dull and colorless, his Japanese are laughable flakes and the story is a vibrant romp through newer paradigms of our outsider's view of contemporary Japan. As someone who actually lived in Japan, Vankin obviously has an encyclopedic knowledge of Japanese pop culture and presents it in a comically extreme form for our amusement. Gone are the samurai and ninja, replaced by ditzy fashion girls and would-be flight attendants, incompetent gangsters, sci-fi pop stars, perverted old men and fast food restaurants. Candy-colored Japan.

I don't know if it's exacly an improvement, but it is closer to what you might actually find if you came here.

Like Vankin, Fisher (who tragically passed away much too young) actually lived in Japan, so I imagine he was able to do a lot more first-hand location scouting than Byrne, Miller or Aparo. Consequently, despite the story's comedic exaggeration, Fisher's Tokyo is almost documentarian in its accuracy. Oh, like Vankin, Fisher takes some license here and there, but only in the service of the narrative. Here's his version of Ikebukuro, one of Tokyo's busiest but somewhat second-rate districts. Sorry, Ikebukuro! I love you but I mean "second-rate" compared to trendier wonderlands like Shinjuku, Shibuya and Harajuku:

To my eyes, the backstreets of Tokyo-- the places where people actually work and live as opposed to shop and play-- look like this. A bewildering jumble of high-rise buildings in dull concrete, stretching from horizon to horizon. No comic book story (and few movies) can prepare you for Tokyo's immense scale. Once inside, you are in an artificial world of steel and glass and after a while, it's hard to imagine there are any other environments on earth.

Here's a photo I took in Ikebukuro:

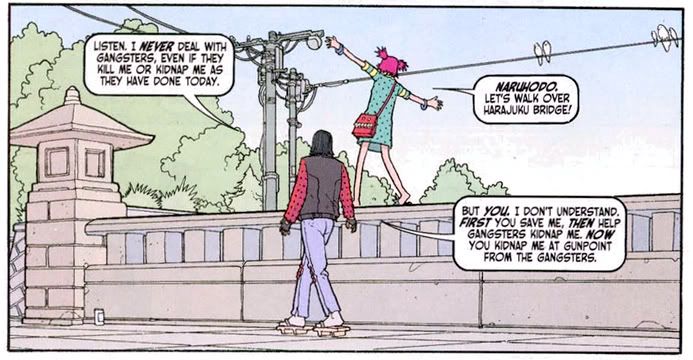

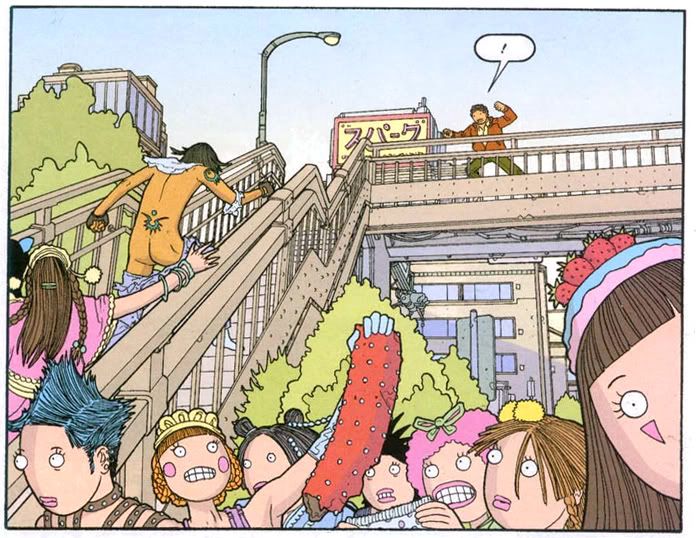

As Vankin's story unfurls, Fisher treats us to backdrops of some of the coolest places on earth. Here's a panel where crazed schoolgirl (another trendy stereotype) Maki has kidnapped her idol Hike to show him off to her Harajuku girl friends. This is more than likely Takeshita-dori, which during the 1990s was the epicenter of Japanese youth fashion culture:

That's one problem with Vertigo Pop: Tokyo!-- Japan's trends change so fast what was current as recently as 2002 is practically antediluvian now. And a lot of the elements in the story seem more contemporaneous with the mid- to late-1990s. Well, perhaps not a problem, per se, but more a transmuting it to a kind of literary time capsule or period piece. Jidai geki for the visual-kei set. And here's the real Takeshita-dori as it appears today:

As you can see, Fisher pretty much nails it and I was standing in almost the exact same spot the panel appears to depict. If an artist draws Takeshita-dori as crowded as it truly is, we wouldn't be able to see the main characters at all. Behold Takeshita-dori in all its glory:

It can take you thirty minutes to an hour to walk its length on the weekend. Unfortunately for this story (and Gwen Stefani), the classic Maki-style "Harajuku Girl" doesn't really exist in that form anymore. She's been name-branded out of existence in Harajuku, subsumed by gothic lolitas and cosplayers and driven by photo-happy tourists to quieter, trendier neighborhoods like Kichijoji (where my own personal version of Maki eventually settled). But FRUiTS magazine continues to document her colorful, creative stylistic heirs faithfully so there's still some hope. Here's an image set just outside Yoyogi Park proper, crossing the Yamanote Line rails in Harajuku:

Here's the park itself, in reality. Fisher almost perfectly matches the real-life location. The lower wall is bit taller in the real world and there are some slight differences in the end caps, but it's instantly recognizable:

Here's the park itself, in reality. Fisher almost perfectly matches the real-life location. The lower wall is bit taller in the real world and there are some slight differences in the end caps, but it's instantly recognizable:

You can even spot the exact location crazy-pops Maki daringly tightrope walks along the wall. It's roughly between the guy in the light shirt and khaki slacks and the person in the face mask in this photo:

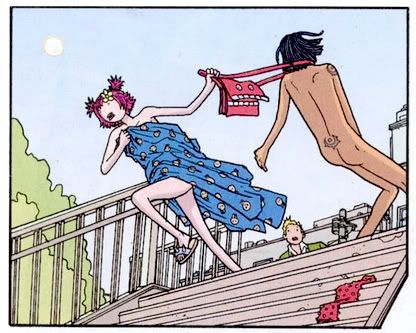

But I don't advise you to duplicate her stunt. If you fell and were injured or killed, I'd feel somewhat responsible and your friends and family would sorely miss you. Part of the action takes place on the pedestrian bridge overlooking the park:

I end up on this bridge every time I visit Tokyo so I can attest to Fisher's accuracy, even with a bit of artistic license. While the color is wrong (although it may have changed from 2002, the year the story is set, to today), Fisher gets the basic look of the bridge itself down, and even includes some of the surrounding greenery:

There's one moment where two characters fall off the bridge and land in the park plaza below, which is almost impossible. The bridge doesn't span the park; it crosses the street over a busy intersection. If they'd have fallen, they would've instantly been run over by cars, as you can see here:

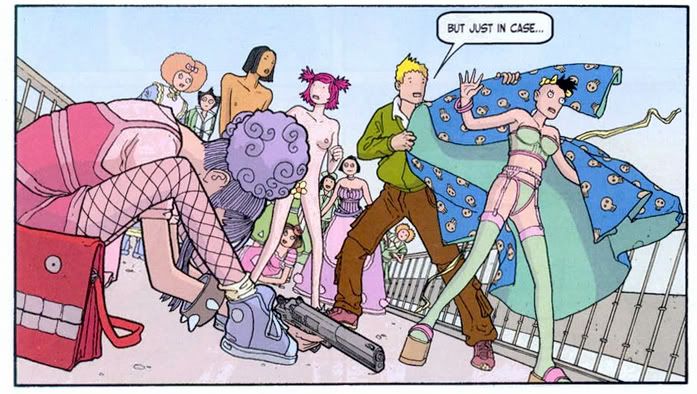

Also, notice that it's not a single span but several, in a rectangular shape. Here's in interesting scene where a nearly naked Maki attempts to escape the chaos she herself has caused, dragging a completely nude Hike behind:

And this is my best guess as to where this event occurs:

And this is my best guess as to where this event occurs: I stupidly shot this photo from the top rather than matching the comic book panel's lower angle from the bottom. Oh well, maybe next time.

I stupidly shot this photo from the top rather than matching the comic book panel's lower angle from the bottom. Oh well, maybe next time.So how do our comic book artists fare with their depictions of Tokyo? Not bad at all. Fisher obviously takes the prize, but the old school dudes pleasantly surprised me. In my memory, they were all much less accurate but I'm gratified to be wrong and actually able to praise these guys for how "right" they got Tokyo rather than rag on them for falling far short. Sure, each could've done a bit more research and gotten it exact, but I doubt either Marvel or DC were willing to spend that kind of money for location sketching. Plus deadlines and all.

Remember-- it's pretty easy for a writer to type "Wolverine hops a jet and lands in Tokyo, then takes a taxi to Shinjuku. On the way there, fighting jet lag, he marvels at his own face gazing down at him from various advertisements in the wild neon lights down the sides of buildings along the street," but the artist has to take those words and make them at least somewhat visually plausible. And Byrne, Miller, Aparo and Fisher accomplish that with their work in these books.

I still have this desire to find some of the actual locations from Yazawa Ai's glorious comic book creation Nana, including Jackson Hole where I plan to try a Jackson Burger (Hachi swears by 'em). Yazawa gets around the accuracy and time constraint issues by using actual photographs as her backgrounds.

Until then:

Bai-bai!

Bai-bai!

No comments:

Post a Comment