Last week, I found a fantastic post discussing Cassandra Cain, the martial artist formerly known as Batgirl. Apparently, someone, somewhere, brought up Cass as learning impaired, possibly autistic. Innerbrat makes a compelling counter-argument and refers to Cass as "a linguistic minority," a phrase I find particularly apt. Also worth reading is Parsimonia's response in the comments section.

In my Batgirl reading days, I never considered this possibility. For one thing, I saw-- and continue to see-- Cass as a unique case, one possibly unclassifiable by any standard behavioral science. I mean, that's comic books for you. What superhero books do is give you something impossible and then try to at least make it plausible. A guy can fly because he absorbs solar radiation in some unknown way. Another can turn his body into flexible steel because he's a mutant. This woman was created from clay and infused with power from one Greek god or another. That one received a blood transfusion from her cousin who had some kind of accident involving gamma radiation. Oh yeah, and then there's this girl who was raised in silence and tortured by her martial artist father so that she would grow up able to predict her opponents' moves and counter them. In Cass's case, there's so much potentially going on there, it's difficult to narrow her down.

But because teaching is one of my many professions, I have thought of Cassandra Cain in terms of ESL, as an English as a second language learner, with physicality being her first. Her native tongue is, quite literally, the ass-whipping or the beat-down. I spent two years teaching developmental English grammar at a community college. My students there were people in their late teens or mid-twenties, sometimes older, non-traditional students, who hadn't scored high enough on the placement tests to take English 101. Some of these people, unfortunately, were barely literate. More recently, I spent six years teaching children and adults conversational English in Japan.

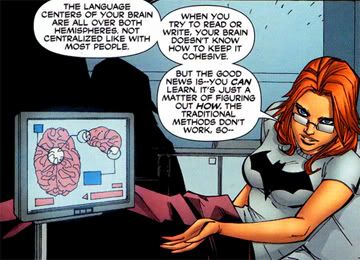

Why rely on my clumsy description when you can check out Barbara Gordon's neat-o visual aids? She's like a human USA Today! Apparently, by the time of the Redemption Road miniseries, "traditional methods" would work exceptionally well.

Why rely on my clumsy description when you can check out Barbara Gordon's neat-o visual aids? She's like a human USA Today! Apparently, by the time of the Redemption Road miniseries, "traditional methods" would work exceptionally well.

Even thought as we perceive it is made up of language. One of the major themes of George Orwell's 1984 is this importance of language to thought. When one is denied certain words, one is denied certain concepts. Imagine a person denied all words. How would such a person perceive the world? Orwell posits a Newspeak translation of Jefferson's Declaration of Independence as simply "crimethink." For Cass Cain, the same document might translate into jumping off a roof. Or the happy feeling she gets when one of her roundhouse kicks impacts some poor sucker's face in the most satisfying of ways.

All that aside, as Cass acquires spoken language and an ever-growing vocabulary over the course of the series, the writers depict this through the way they write her dialogue and narration. In Batgirl issue three, a strange psychic reconfigures her brain so she understands English without being able to speak it; this costs her almost all of her "action predictive" abilities and leads her to seek out Lady Shiva for help regaining them. At this point, Kelley Puckett presents non-verbal Cass, fascinated by a new world of meaning, where objects suddenly have names.

Now that Cass knows the word "razor," she can understand its metaphorical or idiomatic usage.

Now that Cass knows the word "razor," she can understand its metaphorical or idiomatic usage.

This is something we generally take for granted, but for Cass it proves to be a dazzling revelation and involves not only a new, invigorating way of perceiving the world around her, but also a shift in her sense of self. I wish Puckett had devoted a few more pages to this stuff, but his stories are so fast-paced and action oriented, catching character development is like tracing the movement of a hummingbird's wing muscles with your eyes; it exists, it does its job, but good luck seeing it in action.

Within a few issues, Cass begins communicating not just with gestures but with single words, or short phrases. By the end of the series, Andersen Gabrych goes with a first person narration, and Cass speaks directly to the reader in a halting way, frequently using "um" as a hesitation device. I was always fascinated by my students' use of Japanese language hesitation devices while speaking English, most frequently the expression, "Eh to..." Hesitation devices are reflexive, unconscious things and difficult to deal with-- think of someone who habitually drops "You know" into conversations. Cass might pick this up from Barbara Gordon or Stephanie "Spoiler" Brown-- I doubt Batman ever hesitates or stammers-- but she's just as likely to drop hesitation devices entirely.

This was also common with my Japanese students, especially when they were formulating replies. Instead of starting a sentence with "Um..." or "Lemme see" the way an English native speaker might, a Japanese ESL student sometimes says nothing at all for a long, awkward stretch, and can give you the impression he or she either didn't understand the question or simply didn't hear it. Sometimes students would pause this way because they were laboriously mentally translating from English to Japanese and vice versa, but whatever the reason, our conversations proceeded in fits and starts and required a lot of patience from all participants. In terms of storytelling, this would probably add a few too many dialogue-free panels and disrupt the pace, so giving Cass a similar tic probably wouldn't work in a comic book unless it's mentioned by another character.

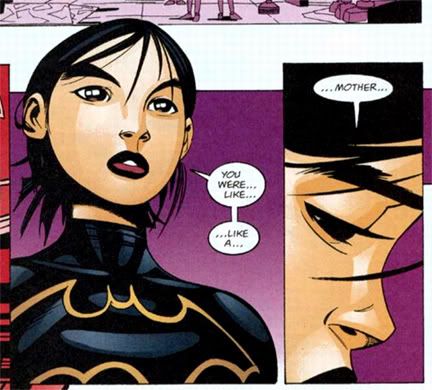

Cass's halting speech, Puckett-style. Writers would continue in this vein for most of her regular series. In the hands of less capable writers, she'd become a veritable Chatty Cathy.

Or if Kojima Goseki illustrates it from beyond the grave. That guy could do almost anything on the page!

I enjoy how Gabrych depicts Cass as fascinated with idioms and expressions, especially ones learned from action movies. It's not something he overuses, and he gives Cass a self-awareness in these scenes that I found quite believable, even if his hackneyed plots and story direction don't do much for me. Giant biker trolls? Yeah, no thanks.

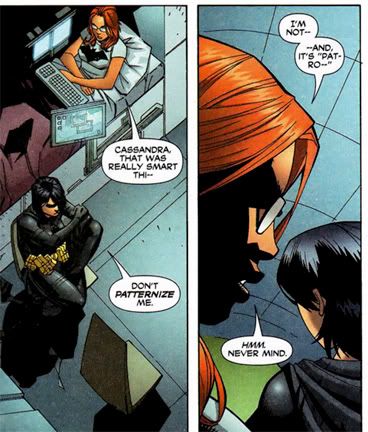

Malapropism or egg corn? You be the judge!

Malapropism or egg corn? You be the judge!

As an ESL teacher, I encountered many very bright people, many much more intelligent than myself-- including a trilingual (Japanese, English and Spanish) close friend-- who didn't quite know how to sugarcoat opinions and consequently came off as a bit blunt or brusque. In various issues, writers occasionally give this characteristic to Cass, usually to humorous effect in conversations with Spoiler or Oracle; I would have liked to have seen this effect used even more because it taps into some of Cass's underused comedic potential.

How might future writers otherwise depict Cass grappling with fluency in a believable way? From my experience with English students, I suggest subject-verb agreement problems, occasional gender pronoun confusion (using he and she interchangeably, or overusing one to the exclusion of the other), awkward circumlocutions, dropping articles or substituting incorrect ones, confusing singular and plural nouns (or simply using singular ones) and using the past progressive verb tense when simple past would do:

Batman: How was your weekend, Batgirl?

Batgirl: Last weekend, I was kicking Penguin's ass.

Of course, after the final Batgirl issue, Cassandra Cain disappears from DC Planet only to return as an extremely talkative Dragon Lady in a leather dominatrix get-up; suddenly not only was she fluent in English at a native speaker's level, but also in Navajo. Well, maybe in a universe where an alien who flies and can stop the earth in its orbit fights crime wearing a red, blue and yellow circus costume.

But even in such a world, it's still disappointing when professional writers go for retread storylines and tired-- or in this case, offensively stereotyped-- characterizations when rich story veins go untapped. After all, English is a pain in the ass to learn. Don't believe me? I can ask a number of people in all walks of life, from high school students to doctors of psychiatry who could convince you.

Some critics of the character apparently felt a non-verbal Cass was somehow a silenced Cass, but this is far from true. As Innerbrat intriguingly suggests:

I think the Cassandra Cain, the second Batgirl, represents someone who signs.

That, my friends, is just brilliant. One doesn't have to speak out loud to express volumes of meaning. Cass's natural form of signing would be different than American Sign Language and feature more jump hook spin kicks. Perhaps a writer could show she's developed her own, unique vocabulary based on what she knows best-- fighting and full body movements, with ways to express her thoughts through something akin to dance. To make things even more complex, it would affect how she interprets abstract concepts and artistic works. How might she comprehend Shakespeare and could she have translated one of his plays into something understandable? Would she enjoy the more violent ones like Macbeth and Hamlet? Would she receive more meaning from ballet or opera, or even a musical with dancing than from a dialogue-heavy drama? This would have added a wealth of character detail to Cass's narrative. Has anything like this ever been done in comics?

Another analog that occurred to me recently was Cass as feral child. Not necessarily one raised by animals, a la Mowgli and Tarzan (although we could make a convincing argument they, as well as Huckleberry Finn, should be included among her literary antecedents), but a child horribly abused and isolated from almost all nurturing human contact, certainly one poorly socialized to an extreme she'd more than likely become a seminal case study with a syndrome named after her. Cass's childhood is harrowing by any standard-- not so much because her father raises her without conventional language, but because for all intents and purposes, he physically and psychologically tortures her. After she breaks with him, she lives apart from society, existing on its fringes throughout her late adolescence and early teen years. This period of her life has never been fully depicted, but we can imagine it as beyond Dickensian in its impoverishment both physically and socially. This is similar to orphan children running wild in war zones, or in urban wildernesses.

Researching this for a more in-depth treatment of the "Cass as feral child" concept, I found a "set of pointers to non-Nativist linguistics and psycholinguistics" (with a critique of Noam Chomsky I can barely comprehend because I'm a nitwit) by Timothy Mason, who writes about the case of a 13-year-old girl:

According to the neuropsychologist, Eric Lenneberg, in his book Biological Foundations of Language, 1967, the capacity to learn a language is indeed innate, and, like many such inborn mechanisms, it is circumscribed in time. If a child does not learn a language before the onset of puberty, the child will never master language at all.

Cass, however, appears to have learned a kinetic language but not a verbal one. Would her understanding of movement and expression and the intense level of empathy this creates in her allow her to build on this to gain English fluency? Or would she, like many of these feral children, remain largely non-verbal?

All of these questions, like that of Cass's being learning disabled or not, really depend on the writer's intent. But I think we can agree she, like the girl in Mason's report, is a pretty extreme example. Damn, if only her writers had taken her down this story route!

Because the ultimate issue or gripe I have with the abandonment of non-verbal Cass is the narrative rush to turn her into a much less interesting character-- conventionally conversational Cass. Maybe this resulted from a failure of imagination or a fundamental inability to grasp the character by her succeeding scripters, exemplified by writer Adam Beechen's widely derided work. While her villainous turn in his Robin was disappointing, Beechen's indifferently plotted Redemption Road represents Cass's nadir as Batgirl-- saddled with a boss-fighting storyline barely worthy of a coin-operated video game from the 1980s, almost completely devoid of all the unique aspects given to her especially by creator Kelley Puckett, forced repeatedly to voice the old "I wish I were a normal girl" cliches in the mopiest way-- and to quote Batman Begins.

A word of advice-- don't call attention to your own story's inadequacies by referencing a much better one for the sake of a tossed-off gag. One more-- if you're going to have otherworldly martial artist Cassandra Cain yak it up, why have her give voice to banalities? It's as if we were all waiting for Garbo to speak, only to have her tell a fart joke we've already heard and didn't find particularly funny the first time.

Even Beechen's attempt to address Cass as an ESL student is merely an excuse to shoehorn a standard-issue romantic interest into the book in the form of a hunky classmate. Any chance of Cassandra Cain's continued run as a lead character died ignominiously along with Redemption Road's sales.

Chuck Dixon reintroduces a taciturn (and largely clothes-free) Cass in the second issue of Batman and the Outsiders, at which point he might have explored many of these linguistic concepts... or Bryan Q. Miller might have continued to develop Cass and her ever-increasing chattiness as a supporting character in the new Batgirl series... but we see how that ended...

What's next for our girl in black? A career as a stand-up comedian? News anchor on the Gotham Nightly News? Professional soccer commentator? Auctioneer? A starring role in Martin Scorsese's upcoming biopic of television pitchman John Moschitta?

2 comments:

This is a fantastic post. Thank you for linking and for all your thoughts.

Thank you for your initial insights that inspired this whole epic-length rant! And for stopping by and commenting.

I truly enjoyed your original post.

Post a Comment