|

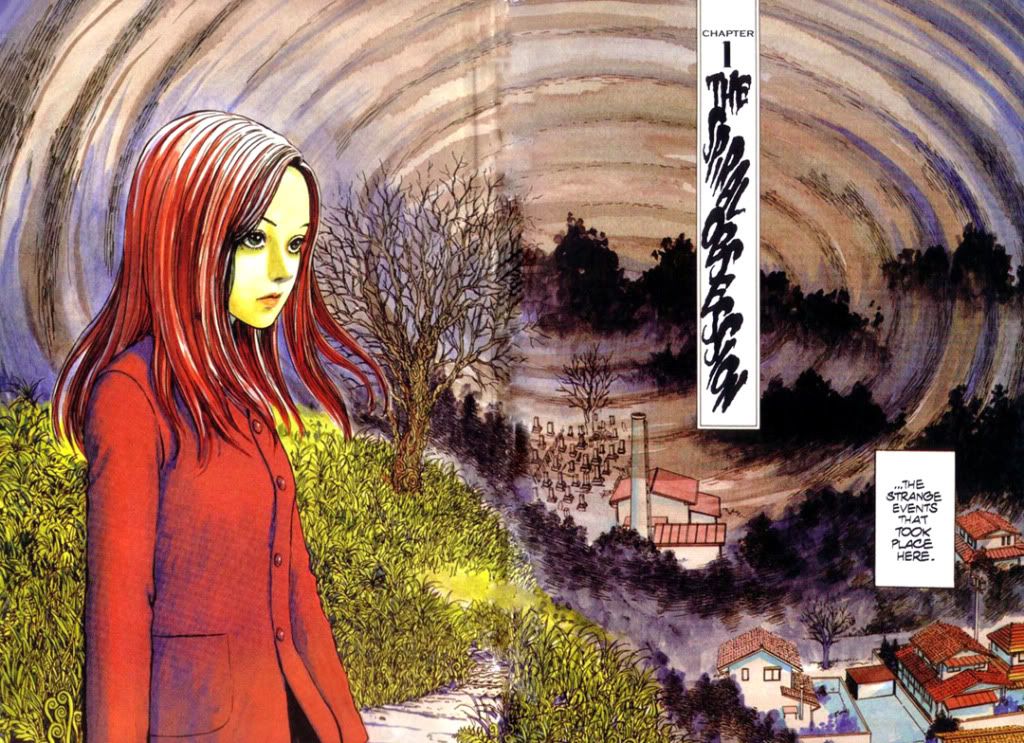

| Junji Ito, Uzumaki (1998-9) |

I don’t know why Junji Ito hasn’t caught on

with manga fans in the Americas. Both

Viz Media and Dark Horse Comics have released very nice books collecting Ito’s work, but

they don’t seem to have made much of an impact there as far as comics culture goes. I think he should be mentioned in the same breath as Mike Mignola, but he seems largely a cultish figure, and somewhat elusive. Dark Horse has two Museum of Terror volumes (the third seems to be out of print) and Viz offers Uzumaki, of course. Gyo is worth a read, although I didn't particularly care for it. It's about dead fish and a killer odor, neither of which inspires much interest in me. But Museum features Ito's most well-known creation-- Tomie, the beautiful, unkillable school girl-- and inspired a hit-and-miss movie series that seems never to to die completely, just like Tomie herself. Uzumaki also became a film, a severely truncated version with a hugely disappointing ending and played largely for laughs. A great deal of

Ito's more recent short stories and other tales-- many of which are

absolutely brilliant-- haven't been made available in English other than

through "scanlations."

What is Ito like in his every day

life? Probably just another hard-working

mangaka. A regular kind of guy who puts in long hours at the drawing table. After all, before he began his comics career and started creating chills and thrills, he was a dental technician. But in his stories, the man reveals a seriously twisted genius. His characters inhabit a universe ruled by dream logic, by malicious forces acting either arbitrarily or for capricious reasons beyond our human understanding. Whatever it is, it's a dark, pitiless place with little hope for escape or redemption. Ito's work is true horror and the man doesn't really have any peers, because no one working in the genre can touch him.

While I was an imaginative little kid who often spent sleepless nights after reading even the mildest of DC ghost stories, as an adult I’m pretty hard-boiled when it comes to printed horror. Uzumaki, Ito’s masterpiece, gave me a serious case of the creeps. It made my stomach churn. Even today, years after I initially read Uzumaki, moments from the story recur in my mind, like childhood nightmares recalled time and again in broad daylight, in the most unexpected of places. Writing this, I suddenly feel it faintly in my nervous system, on my skin, as if it Ito himself tattooed itself there, indelible. As the old idiom goes, it's as if someone walked on my grave.

While I was an imaginative little kid who often spent sleepless nights after reading even the mildest of DC ghost stories, as an adult I’m pretty hard-boiled when it comes to printed horror. Uzumaki, Ito’s masterpiece, gave me a serious case of the creeps. It made my stomach churn. Even today, years after I initially read Uzumaki, moments from the story recur in my mind, like childhood nightmares recalled time and again in broad daylight, in the most unexpected of places. Writing this, I suddenly feel it faintly in my nervous system, on my skin, as if it Ito himself tattooed itself there, indelible. As the old idiom goes, it's as if someone walked on my grave.

Kirie Goshima is a normal high school girl,

another of Ito’s fragile, doll-like female protagonists. She lives in Kurozu-cho ("Black Vinegar Town"), a seaside town like many

here in Japan. Sea for one border,

mountains for another. Kurozu-cho is a little

cut off from the rest of Japan thanks to geography, and it has a mysterious

past. Little by little—a whirlwind here,

a guy obsessed with swirling his miso soup there—Kirie discovers to her growing

horror an ever-pervasive influence by the spiral. No ghosts, no monsters, just a simple shape

curving in on itself. Kirie‘s boyfriend Shuichi has already noticed things not quite normal and is coming unraveled. Kind of like a thread from a blanket that

curls in your fingers as you try to pluck it.

And with that simple set-up, life for the two luckless teens increasingly spirals out of control. Ito tells the story in

vignettes, from Kirie’s point of view; Shuichi has introduced the girl into a world where literally anything can be perverted by

the pernicious influence of the spiral.

After a couple of early chapters, each of which tends to follow a formula of developing a premise, developing it, then delivering a disgusting punchline, you begin to anticipate what the spiral will do

next. The results still shock.

Like diseased mushrooms, events grow inexorably out of each other and transformations and mutations abound. As the spriral closes in, Kurozu-cho darkens to a place where a girl with a crescent-shaped scar on her forehead becomes a monstrous entity, a boy obsessed with pop-up surprise scares becomes a ruined jack-in-the-box figure and even the joy of birth becomes the stuff of nightmares. The signal transformation involves a particularly slow-moving classmate of Kirie’s. His physical and mental changes are off-putting enough by themselves, but just when you think you’ve reached the point where you can somewhat live with the memories (or at least resume your normal diet), they maddeningly recur to other characters until the situation escalates to what is arguably cannibalism—or something for which we’ll have to invent a completely new word for gastronomic crimes against humanity. Kirie pursues these rapidly proliferating horrors towards their twisted center, where the story takes on Lovecraftian proportions and escape may prove impossible.

Like diseased mushrooms, events grow inexorably out of each other and transformations and mutations abound. As the spriral closes in, Kurozu-cho darkens to a place where a girl with a crescent-shaped scar on her forehead becomes a monstrous entity, a boy obsessed with pop-up surprise scares becomes a ruined jack-in-the-box figure and even the joy of birth becomes the stuff of nightmares. The signal transformation involves a particularly slow-moving classmate of Kirie’s. His physical and mental changes are off-putting enough by themselves, but just when you think you’ve reached the point where you can somewhat live with the memories (or at least resume your normal diet), they maddeningly recur to other characters until the situation escalates to what is arguably cannibalism—or something for which we’ll have to invent a completely new word for gastronomic crimes against humanity. Kirie pursues these rapidly proliferating horrors towards their twisted center, where the story takes on Lovecraftian proportions and escape may prove impossible.

These are stories to read in the daytime. If you can find them, that is. But be warned—Ito does not flinch from

reshaping his characters to suit the spiral’s whims and a lot of the imagery is

extremely disturbing. Not for tender psyches or weak constitutions. Oh, and don't eat escargot before you read it.

No comments:

Post a Comment