|

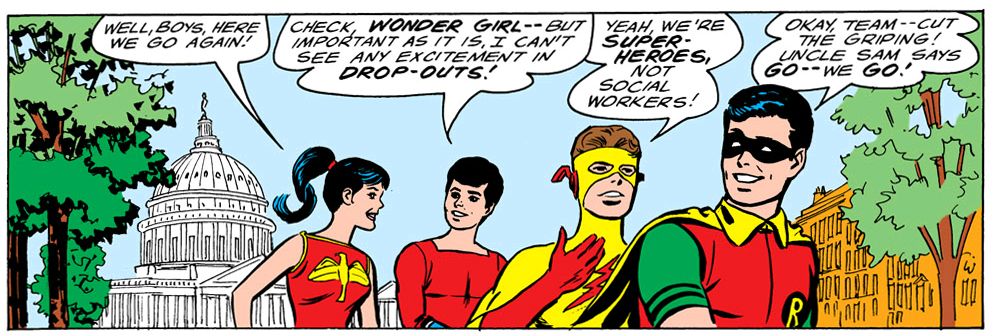

| Bob Haney-script/Nick Cardy-art, Teen Titans #3 (May/June 1966) |

Many years ago, before you and I were even born, the US government needed someone to help with school drop-outs. So they turned to DC's premiere group of costumed teens (most of whom were sidekicks, wards or protégés of similarly-themed adult characters). Calling Robin, Kid Flash, Aqualad and Wonder Girl to Washington, D.C., concerned officials charge them with journeying to the middle American heartland and confronting their age-peers. "Stay in school," the Teen Titans preach, "the United States government wishes it!"

People had youth on the brain back in the 1960s. While adults and kids have always had their differences, the post-WWII baby boom expanded what they used to call the "generation gap" to almost revolutionary levels. It started in the 1950s, but intensified the following decade due to the continued pressures of an unpopular war, struggles for racial and gender equality, new forms of musical, artistic and self-expression, the Sexual Revolution and even the cynical media exploitation of this huge, new-- and relatively affluent-- demographic. With even a cursory reading of history, we can, just as people did back in the 1960s, divide these opposing forces into the establishment and the anti-establishment.

When "The Revolt at Harrison High" in Teen Titans #3 -- with its heroes optimistically working for the establishment writer Bob Haney (himself a self-described socialist and pacifist) characterizes as largely benign-- hit the newsstands in the summer of 1966, the anti-war movement was already in full swing. Young people had already burned draft cards, various groups had successfully staged several

large scale anti-war rallies (Haney had participated in some by this time as well) and a number of veterans had attempted to return their medals to

the White House.

The next year, 1967, witnessed the Summer of Love and the Beatles' psychedelic masterpiece Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band. Colorful Utopian dreams seemed within reach if the young simply turned their eyes to the sky in search of diamonds and tuned their sitars to the cosmic.

Then, in 1968, the world erupted, with the Tet Offensive rocking America's confidence in its military's ability to defeat a technologically-inferior foe, two major assassinations at home, racial violence, student violence, police violence in Chicago during the Democratic National Convention, a Soviet invasion of a liberalized Czechoslovakia, tyranny stamping its iron boot on the human face forever.

Things fractured further. That year, American International Pictures released Wild in the Streets, in which a 24-year-old rock star becomes president of the United States and throws people over 35 into concentration camps where they’re dosed with LSD. Coming years would see more war protests, the watershed music festival Woodstock giving way to legendary bummer Altamont, the Tate-LaBianca Murders (via the demonic influence of Charles Manson-- the perfect hippie bugbear to chill the spines of parents everywhere), the invasion of Cambodia and the 1970 Kent State shootings—an event preceded by the Ohio governor angrily denouncing anti-war protesters on campus as a “militant, revolutionary group.”

The next year, 1967, witnessed the Summer of Love and the Beatles' psychedelic masterpiece Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band. Colorful Utopian dreams seemed within reach if the young simply turned their eyes to the sky in search of diamonds and tuned their sitars to the cosmic.

Then, in 1968, the world erupted, with the Tet Offensive rocking America's confidence in its military's ability to defeat a technologically-inferior foe, two major assassinations at home, racial violence, student violence, police violence in Chicago during the Democratic National Convention, a Soviet invasion of a liberalized Czechoslovakia, tyranny stamping its iron boot on the human face forever.

Things fractured further. That year, American International Pictures released Wild in the Streets, in which a 24-year-old rock star becomes president of the United States and throws people over 35 into concentration camps where they’re dosed with LSD. Coming years would see more war protests, the watershed music festival Woodstock giving way to legendary bummer Altamont, the Tate-LaBianca Murders (via the demonic influence of Charles Manson-- the perfect hippie bugbear to chill the spines of parents everywhere), the invasion of Cambodia and the 1970 Kent State shootings—an event preceded by the Ohio governor angrily denouncing anti-war protesters on campus as a “militant, revolutionary group.”

Then came further betrayals. The crushing loss of George McGovern in the 1972 election to Richard Nixon. Watergate. The energy crisis. Recession. Malaise. Cities like New York suffering from collapsing infrastructure. No wonder youth culture curdled into the nihilism and anarchy of punk rock on one hand and the mindless hedonism of disco on the other.

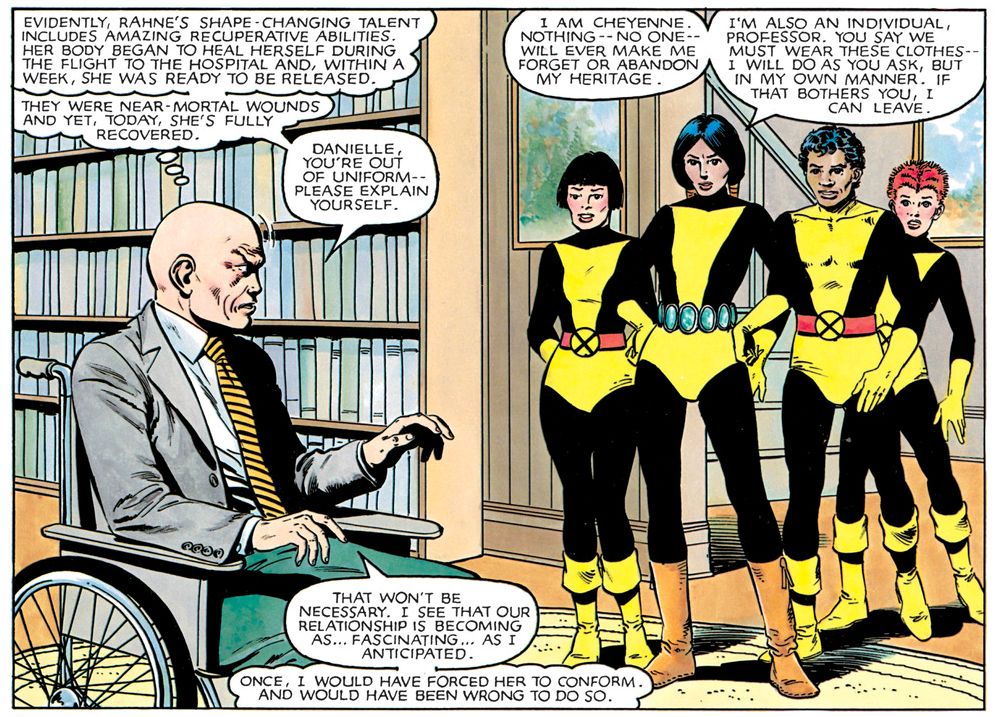

Which might be why just a generation after the Titans marched proudly out of Washington filled with the evangelical furor and a hopeful message for high school drop-outs everywhere, Dani Moonstar of the New Mutants, Marvel’s premiere group for costumed

young people (none of whom were sidekicks, wards or protégés of

similarly-themed adult characters) responds with open rebelliousness to Professor

X’s demand for uniformity among his pupils.

And also why the Professor himself decides not to quash her

individualism.

The two teams take different tactics when interacting with their peers, too. In "Harrison High," the Titans act as

establishment mouthpieces, which renders their attempts at talking frankly with

their age-peers awkward and forced. They fail because few people enjoy being talked down to, especially by others their own

age. This approach pays no dividends, as

the Titans learn here. Later they take a

different tactic-- strangely enough, involving violence-- and find positive results.

|

| Chris Claremont-script/Bob McLeod, Mike Gustovich-art, New Mutants #2 (April 1983) |

The New Mutants, on the other hand, have no ulterior motives-- certainly none that are government-directed-- and relate to people in their age demographic more or less as equals, so their interaction, while a bit contentious, is comfortingly naturalistic. Within moments, the mutant students and the townies have forged the bonds of friendship despite their socio-economic, cultural and genetic differences.

But don't let me give you the idea the Titans didn't learn to swing. It wasn't long before they got with their times and began questioning authority. They'd drop their self-righteous pro-establishment stance and come into conflict with their mentors and the adult world at large. That's an essay for another time. But just think about this-- today Robin is a grandfather and Dani is my age and they're both just as confused and troubled by today’s kids as the grown-ups of yesteryear.

2 comments:

Great comparison! I never thought of these two together this way, but you make it sound like it makes a lot of sense.

Mind you, seeing these panels side by side brings home the realization that Claremont's dialogue was every bit as arch and stylized and theatrical as Haney's was...not that I consider that a bad thing in either case.

Thanks! About the dialogue thing-- absolutely! That's a topic we need to get into sometime, too. Actually, if I have to choose, I prefer Haney's hip-cat slang.

Post a Comment