Thursday, April 25, 2013

We interrupt Kamandi Month for a couple of Batman sketches...

You know I really had the best of intentions with this whole Kamandi Month thing but non-Great Disaster disasters have really taken a bite out of my free time. So to make it up to you, here's an art offering. Enjoy!

Tuesday, April 16, 2013

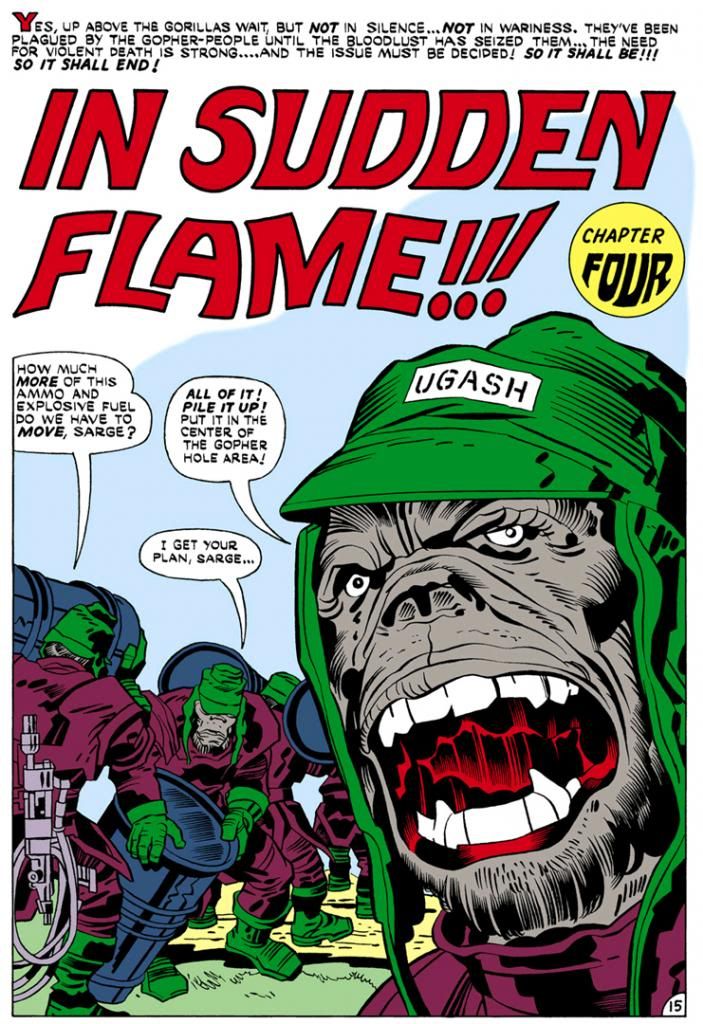

April is Kamandi Month: Who gash? Ugash!

|

| Script/pencils: Jack Kirby, inks: D. Bruce Berry (Kamandi #18, June 1974) |

Those are just the ones I know by heart. You could usually identify these guys by their ubiquitous derby hats or well-chewed cigars, or both. Or, in the case of Sgt. Ugash, a green cap (with his name printed on it!), purple jumpsuit and lots and lots of hair.

Sgt. Ugash first appears in Kamandi #17 (May 1974) and he's as rambunctious from the get-go as any of those other classic Kirby creations. He's not only fighting the tiger army, but he's also having trouble keeping his troops supplied because the gopher people keep tunneling up under the ape bivouac and stealing everything they can get their clawed hands on. Pumping water, bullets and fire into the holes doesn't solve the problem, so Ugash sends Kamandi down like a ferret with bombs strapped to his back. That rascally Kamandi, of course, turns on Ugash, so the sergeant and his ape soldiers spend the next couple of issues pursuing the Last Boy on Earth, who fights back using a giant worm, the likes of which would make Maud'Dib's mouth water at the thought of riding it against the Harkonnen hordes. We might consider this some kind of phallic symbolism. If big apes represent masculinity run amok, then it takes a really big dick to beat a really big ape.

By Kamandi #20 (August 1974), however, Kirby has abandoned the tiger-gorilla war and forced Sgt. Ugash and Kamandi into an unfriendly alliance against the Roaring Twenties-style robots inhabiting Chicagoland. Some chump years before the Great Disaster decided it would be a hoot to build a theme park based on Chicago's violent Prohibition days and equip the various factions with real bullet-spraying tommy guns. This theme park-designing asshole must not have watched Westworld; I'm guessing Kirby did, or at least absorbed a little of it from television commercials.

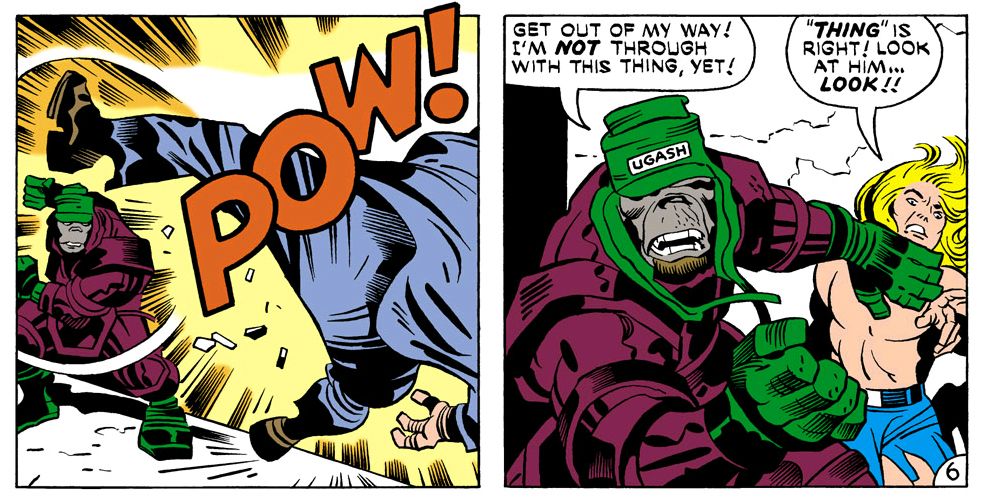

Kamandi #20, "The Electric Chair!!!" This was my first Kirby comic, my first encounter with Sgt. Ugash. This single issue of Kamandi came my way and as far as I knew, Ugash co-starred in all the others as well. As a Planet of the Apes fan, I immediately liked him more than the kid who gave his name to the comic. Plus, Kamandi reminded me of the filthy hippies we saw on the news, or one of my oldest brother's baseball teammates who sometimes teased me or got drunk at our house and barfed in my bedroom when my parents went away for the weekend. Throughout the story, Kamandi tries to use reason and puzzle out what's happening, a rational but-- to a child reader-- unsatisfactorily unassertive way of dealing with the situation. Ugash couldn't care less about the whys of Chicagoland; he simply starts smashing the place. But for me, Ugash had another thing going for him besides ape-appeal and hands-on approach to problem solving.

|

| Kirby/Berry (Kamandi #20, August 1974) |

Even then, we understood the futility of those kinds of grand gestures (rebellion in the 1970s meant spankings both at home and at school, or at least the dreaded "writing lines" in the principal's office, which kept us trapped well past the final bell), but what Kamandi did seemed shameful. In retrospect, it makes a lot more sense-- Kamandi splits.

Labels:

Brooklyn,

D. Bruce Berry,

Dan Turpin,

DC Comics,

good art,

good writing,

Jack Kirby,

Kamandi,

Kamandi Month,

Ugash,

vintage comics

Sunday, April 14, 2013

April really is Kamandi Month: Sorry for the delay!

Yeah, Kamandi Month has run into its own Great Disaster. This one is made up of several mini-disasters: 1) the school year just started and I have more classes to teach, 2) my fiancee was ill all last week with a stomach virus and I had to take care of her and 3) I'm working on my own comic (spoiler alert-- it sucks!). But there will be some Kamandi posts. Some of them are finished, some are in rough draft form and all are waiting for me to get some of that elusive free time that I feel wouldn't be better spent drawing. Oh yeah-- and I don't like to post things about Kamandi unless they're illustrated with some cool Jack Kirby art. That way there's at least one positive thing about each.

I know millions of Kamandi fans are waiting for what I have to say about the series and I hate to disappoint them. Sorry!

I know millions of Kamandi fans are waiting for what I have to say about the series and I hate to disappoint them. Sorry!

Saturday, April 6, 2013

April is Kamandi Month: On Command D

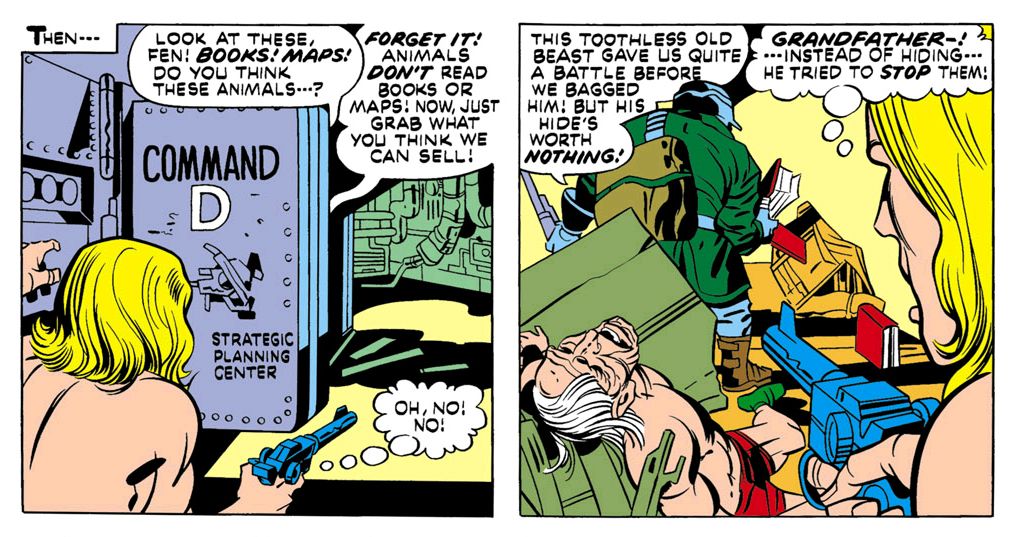

When we speak of “Command D,” what is it we’re talking about? Specifically, the underground bunker in which Kamandi grew up, raised by a white-haired man he believes to be his grandfather. Given their relative ages there must have once been younger people in the bunker-- Kamandi’s parents. Kamandi doesn’t mention them, so it’s likely they died when he was an infant, leaving him in the elderly man's care. I'm immediately reminded of Pitcairn Island of HMS Bounty fame, when an American whaling ship found John Adams (sole male survivor of the mixed group of English mutineers, Tahitian men and women who sailed into legend) as aged patriarch of a small society there.

I take writer/artist Jack Kirby at his

word when he describes Kamandi as the old man's grandson, at least in terms of the boy's belief they're related. Kamandi refers to him as Granddad at the story's outset and Grandfather the rest of the way, and while these may simply be culture-based honorifics, the narration calls him Kamandi's grandfather so have no reason to doubt he is biologically rather than simply functionally. Whatever the true nature of their relationship, someone named the boy after the bunker, either

his parents, grandparents, simply the man known as Grandfather, or some other subsequently deceased co-survivor

(Kamandi’s dialogue doesn’t hint at such, so that doesn’t seem likely). Spelling seems not to have mattered, or else this mysterious person or people decided Kamandi seemed more appropriate for a boy's name than Command D.

The story begins with Kamandi having emerged from his namesake domicile and received massive culture shock— Grandfather with his memory tapes and micofilm has inadvertently acted as an unreliable teacher and has not only failed to prepare Kamandi what he encounters in the post-Cataclysmic world, he also imparted in the boy certain goals that at first glance seem unattainable. Kamandi has been trained, if not disciplined. That Grandfather has passed on some mistaken assumptions is to be expected.

Because his knowledge of the story's settings approximates ours, Kamandi acts as our masking agent, and we are meant to identify with him and his solitary plight. Positing the typical comic book fan who might be attracted to Kamandi: The Last Boy on Earth as approximately the character’s age and gender, or perhaps younger and able to imaginatively inhabit the protagonist’s role, that is. So it’s necessary at this point in the story for Kamandi to possess a naiveté so that we might experience the story surprises and twists along with him. It’s an age-old gambit in fiction (Stephen Crane and Horatio Alger would probably approve) and Kirby, being a born storyteller and a past master of the “kid gang” comic, appropriates it.

The story begins with Kamandi having emerged from his namesake domicile and received massive culture shock— Grandfather with his memory tapes and micofilm has inadvertently acted as an unreliable teacher and has not only failed to prepare Kamandi what he encounters in the post-Cataclysmic world, he also imparted in the boy certain goals that at first glance seem unattainable. Kamandi has been trained, if not disciplined. That Grandfather has passed on some mistaken assumptions is to be expected.

Because his knowledge of the story's settings approximates ours, Kamandi acts as our masking agent, and we are meant to identify with him and his solitary plight. Positing the typical comic book fan who might be attracted to Kamandi: The Last Boy on Earth as approximately the character’s age and gender, or perhaps younger and able to imaginatively inhabit the protagonist’s role, that is. So it’s necessary at this point in the story for Kamandi to possess a naiveté so that we might experience the story surprises and twists along with him. It’s an age-old gambit in fiction (Stephen Crane and Horatio Alger would probably approve) and Kirby, being a born storyteller and a past master of the “kid gang” comic, appropriates it.

Grandfather expects Kamandi singularly to “reclaim”

a shattered world for humanity.

Unfortunately, given the ruins Kamandi encounters, the feral and mute nature of the first humans he encounters and the rule of

talking animals with their mastery of firearms and motor vehicles and firmly-established feudal kingdoms and small empires, one boy—indeed,

the “last boy”—seems to have little chance at re-establishing humanity’s

dominance. And should humanity, the

species responsible for the current topsy-turvy nature of the planet, be

allowed this second (or third, or fourth) chance? Might the world be better off, or at least no

worse off, in the hands of various tigers, lions and gorillas, all of whom seem

to have inherited humanity’s various vanities and prejudices?

Fortunately, in all other aspects, the Grandfather’s tutelage was more than enough, as we’ll see when Kamandi adjusts psychologically to his changed circumstances and shattered belief system.

Fortunately, in all other aspects, the Grandfather’s tutelage was more than enough, as we’ll see when Kamandi adjusts psychologically to his changed circumstances and shattered belief system.

What is the nature of “Command D?” Who built it?

At this point in the narrative, Kirby is content to leave us with hints. This is all set-up. The point is getting Kamandi out of his

comfort zone and to thrust him into adventure so we might experience his world

and encounter its mysteries along with him.

For now we may assume Command D to be some

sort of military safe-place. The name

suggests so. Command D. Kirby, having shaped by his combat experience

in the European Theater of Operations during WWII, was familiar with this type

of militaristic nomenclature. We can't be sure which service branch operated the bunker. On the outside, Kirby places what appears to be a United States Air Force insignia, but within we find the partially obscured words "US AR" (or perhaps even "US AP"), which suggests it might have been an army facility.

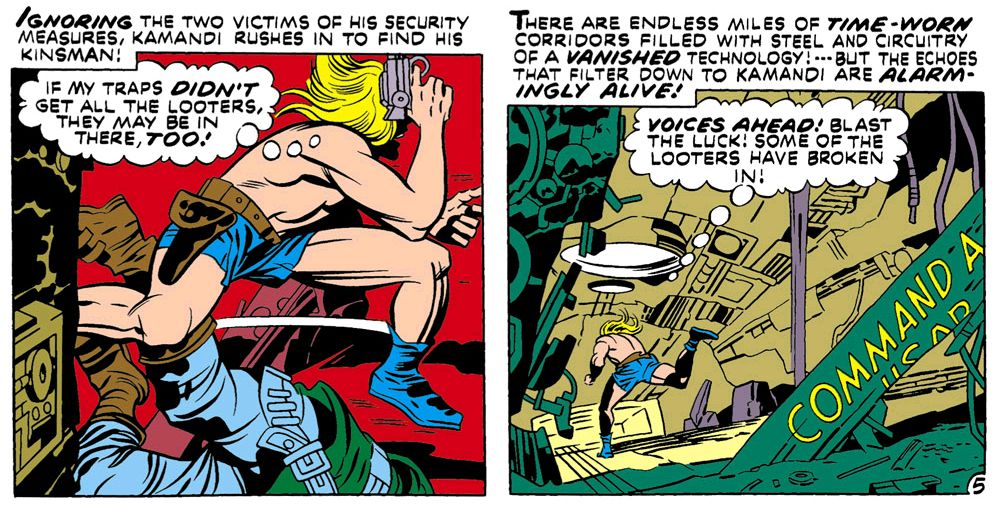

From its alphabetical coding, and thanks to a sequence where Kamandi returns from his initial surface foray to discover his home invaded and runs through them, we know there are other Commands, with A being the closest to the surface; Command D features a door labeling it the "Strategic Planning" section. From whence the great military and scientific brains of the past held forth, no doubt.

Someone from this class realized things were beyond the tipping point and descended into this vast underground complex of heavy safe-like doors where they seem to have kept certain martial traditions and at least a few elements of 20th century (i.e., contemporary) culture and mores. Kamandi possesses a complete body of knowledge from that era and speaks as any mid-1970s teen might (albeit minus period slang, fortunately). As we also see, he's very handy with firearms and skilled in hand-to-hand combat.

From its alphabetical coding, and thanks to a sequence where Kamandi returns from his initial surface foray to discover his home invaded and runs through them, we know there are other Commands, with A being the closest to the surface; Command D features a door labeling it the "Strategic Planning" section. From whence the great military and scientific brains of the past held forth, no doubt.

Someone from this class realized things were beyond the tipping point and descended into this vast underground complex of heavy safe-like doors where they seem to have kept certain martial traditions and at least a few elements of 20th century (i.e., contemporary) culture and mores. Kamandi possesses a complete body of knowledge from that era and speaks as any mid-1970s teen might (albeit minus period slang, fortunately). As we also see, he's very handy with firearms and skilled in hand-to-hand combat.

But what became of the others who dwelt in the complex? The

inhabitants dwindled and vanished. Other

“last children” might have made journeys like Kamandi’s, only to come to

grief. It’s a dangerous world out there,

post-cataclysm, as Kamandi soon discovers.

Labels:

Command D,

DC Comics,

Jack Kirby,

Kamandi,

Kamandi Month,

vintage comics

Thursday, April 4, 2013

Good bye, Mr. Infantino

I thought the only bad news we'd get today was the passing of Roger Ebert, that tremendously gifted film reviewer, personality and, in recent years, prolific blogger. But now comes word Carmine Infantino has also died. Infantino had as great an influence on my sensibilities as Ebert did on the way I express my thoughts about them. Which is to say, quite a lot, even though it rarely shows because I'm a stinky writer and artist. Those two guys were gigantic in their respective fields.

Infantino is partially responsible for one of my all-time favorite titles, Kamandi by Jack Kirby. That's a book I intend to celebrate all this month for no other reason than I love it. Infantino tried to land the comic book rights to the Planet of the Apes film series and when he couldn't, he smartly asked Kirby to do something similar. It turned out not all that similar, and Kamandi #20 (which does feature talking apes) introduced me to Kirby and ignited a life-long love of the man's work. At the time, I knew nothing of Infantino. Flash foward a few years and I'd become a total nut about Star Wars. Marvel had Infantino pencilling their Star Wars monthly and that was my introduction to both his name and artwork.

Because of Marvel's Star Wars, I'll always associate Infantino with sharp, jutting chins. Some artists just have a certain defining, instantly recognizable tic. Curt Swan's endlessly similar faces, Gil Kane's forehead lines and clutching hands, John Buscema's glower (and Joe Kubert's), Neal Adams's Batman or whoever shouting and pointing directly at the reader, John Byrne's crosshatched cheekbones.

Jutting chins were Infantino's thing, at least at that late stage in his drawing career. When I finally saw some of his earlier Flash and Batman work in some DC reprint digest, I was shocked. Where are the chins?

Oh, and he co-created the Barbara Gordon Batgirl. See what I mean about his influence? Without that character, I wouldn't have another of my comics faves, the Cassandra Cain Batgirl.

Infantino is partially responsible for one of my all-time favorite titles, Kamandi by Jack Kirby. That's a book I intend to celebrate all this month for no other reason than I love it. Infantino tried to land the comic book rights to the Planet of the Apes film series and when he couldn't, he smartly asked Kirby to do something similar. It turned out not all that similar, and Kamandi #20 (which does feature talking apes) introduced me to Kirby and ignited a life-long love of the man's work. At the time, I knew nothing of Infantino. Flash foward a few years and I'd become a total nut about Star Wars. Marvel had Infantino pencilling their Star Wars monthly and that was my introduction to both his name and artwork.

Because of Marvel's Star Wars, I'll always associate Infantino with sharp, jutting chins. Some artists just have a certain defining, instantly recognizable tic. Curt Swan's endlessly similar faces, Gil Kane's forehead lines and clutching hands, John Buscema's glower (and Joe Kubert's), Neal Adams's Batman or whoever shouting and pointing directly at the reader, John Byrne's crosshatched cheekbones.

Jutting chins were Infantino's thing, at least at that late stage in his drawing career. When I finally saw some of his earlier Flash and Batman work in some DC reprint digest, I was shocked. Where are the chins?

Oh, and he co-created the Barbara Gordon Batgirl. See what I mean about his influence? Without that character, I wouldn't have another of my comics faves, the Cassandra Cain Batgirl.

Wednesday, April 3, 2013

Don't Ask: Just Read It! April is Kamandi Month!

There are many things I love and two of the things I love most-- as close friends know-- are Jack Kirby and Planet of the Apes. Sometimes the things I love don't quite fit together, like Kirby layouts and Alex Toth pencils on X-Men #12. But every so often they combine into a third thing I also end up loving. So it was when Cornelius met the King. Kind of.

I've always heard Kamandi resulted when Carmine Infantino asked Kirby to do something like Planet of the Apes. And no wonder-- the films set off a huge merchandise boom that pre-figured the one for Star Wars-- action figures, playsets, garbage cans, board games, coloring books; everything an Apes-happy kid could want. So it's easy to see why Infantino would want to put DC in the talking ape business (also, DC has a long history with apes).

Eventually, Marvel landed the Apes license and produced eleven issues of a monthly series and twenty-nine of a black and white magazine. Neither book drew more than a cultish following, but on another DC-style earth (Earth-K), Infantino worked a deal with 20th Century Fox and Kirby drew the first five or so issues of DC's Planet of the Apes (along the lines of the 2001 adaptation he later produced for Marvel here in our reality) before handing it off to Mark Evanier and a rotating cast of artists.

Go seek out that black hole that's spinning almost at the speed of light. It'll take you right to this fabulous universe, where Kirby's Fourth World epic went exactly as he'd planned it and his Planet of the Apes ran for 150-odd issues and witnessed the art debuts of both Michael Golden and Frank Miller and an annual written by Alan Moore. Bring some of those comics back with you, too. I'd like to read them!

But here in our world, things didn't work out that way. Denied by 20th Century Fox but stuck on his idea, Infantino cancelled Forever People, ripping a hole in the Fourth World, and then put Kirby to work on a derivative tale of talking apes and the end of the world.

How lucky for us Kirby could never contain himself to mere imitation. Instead, he took some old concepts he had rattling around and worked them into a post-apocalyptic tale in his own style, with a rambunctious long-haired teen as its lead and more than just talking apes as villains. In Kamandi's world, not just apes but animals of all kinds talk. They have little kingdoms of their own and wage interspecies war against each other with Kamandi frequently caught between the furred factions.

Marvel's Apes tales, written by Doug Moench and initially drawn by Mike Ploog, went beyond the meagre budgetary considerations of the movie series and gave us all kinds of weird vistas. Giant brains floating in tanks, apes acting like 19th century mountain men, an adventure inside Mount Rushmore, bionic apes. And those crazy city-ships. Kirby's vision was even more expansive, covering the entirety of North and parts of South America, germs from space, radioactive astronauts, Kamandi as a jockey on the back of a horse-sized grasshopper, the fevered paranoia of Richard Nixon and my favorite-- Chicagoland, a Prohibition-era museum city populated by robots enacting all the classic gangster stereotypes of the era.

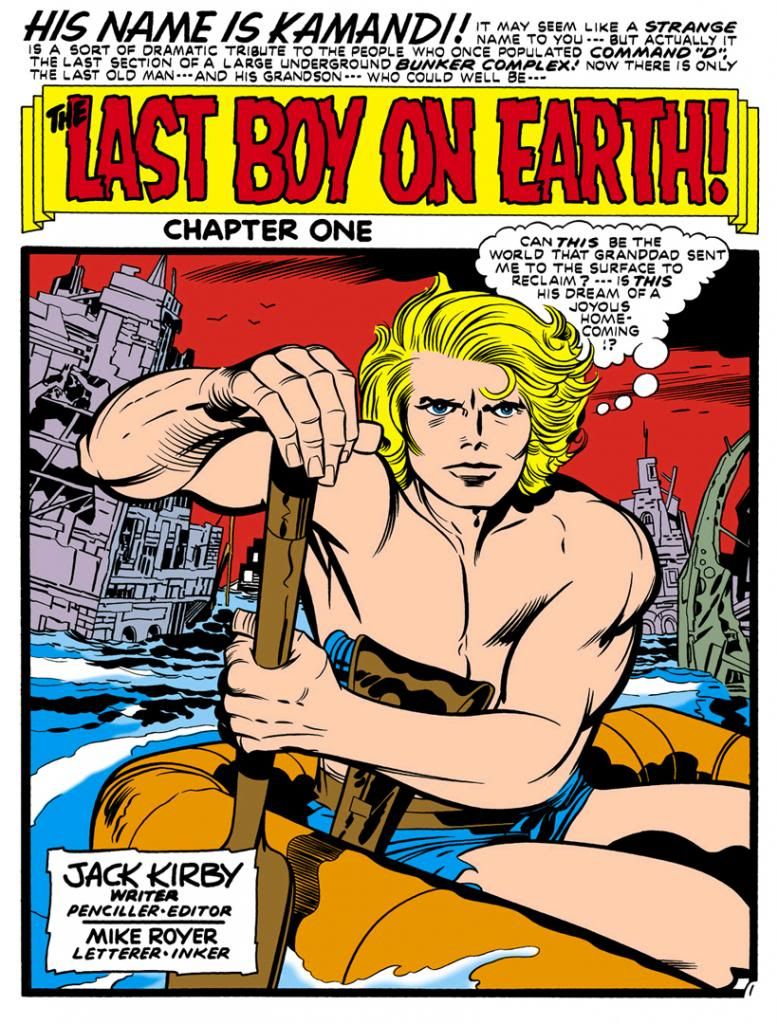

While Moench's "Terror on the Planet of the Apes" opus features Jason, one of comics' true assholes, as its human lead, Kirby's book stars a young man billed as "The Last Boy on Earth." His name comes from the bunker in which he lived with his grandfather, but his looks and personality are made up of purest Kirby.

Actually, Kamandi resembles any number of young dudes who used to terrify me back when I was a kid in the deep south. I mean, obviously we had modern swimming pools way down there in Georgia, but these guys-- and their girlfriends-- also liked swimming in rivers, lakes and "blue holes," where underground aquifers bubbled up in the form of cold springs. Or tubing down creeks. And their swimwear of choice was usually cut-off blue jeans just like the ones Kamandi sports. Like those guys, Kamandi's a roughneck who takes no guff from anyone. Not from lion kings, panther princes, or angry ape sergeants. With his quick temper and shirtless style, Kamandi would fit right in with these Lynyrd Skynyrd-loving southern boys.

He's prettier, though. Look at his glorious hair, the kind even Farrah Fawcett-Majors would have envied in her Charlie's Angels heyday.

And a heck of a lot smarter. Kamandi's got brains. He doesn't just experience his world and fight against it; he searches for answers to all its mysteries. The "Last Boy on Earth" (as the book's subtitle calls him), Kamandi journeys largely alone through Kirby's madcap future, always on the lookout for others like himself and the ultimate answer to how things got so mixed up in the first place. Cortexin, huh?

For the next few weeks, we're going to spend some time with Kamandi and really get to know him, his friends and his world. Come along with me, won't you? Let's close our eyes, drift into comas for hundreds of years and awaken in the future, after the Great Disaster. Humanity has abandoned its cities and fled into the forests. The ascendency of animal-kind has arrived.

Now-- open your eyes.

What do you see?

William Stout also knew Alex Toth...

While we're on the subject of Alex Toth-- one that never seems to exhaust my interest-- another masterful artist you may have heard of who goes by the name of William Stout recently held forth (actually fifth; there are five parts) on his friendship with Toth. Which, like so many others', was a bit... oh... fragile. It's somewhat in response to the first two volumes in the Dean Mullaney-Bruce Canwell epic overview of Toth's life. It's just fascinating stuff and, as Stout takes pains to point out, Toth could be incredibly charming and kind as well. And Stout ends up validating the same sad conclusion I made after finishing Genius, Illustrated. Anyway, I'm hooked.

Speaking of-- this is my first time visiting Stout's page, but it won't be the last. I've liked his artwork ever since I read Dinosaur Tales (Bantam Books, 1983), a collection of Ray Bradbury book with some Stout illustrations in it. Some Stout illustrations. As if they were trifles. William Stout is one of the big dinosaur artists of all time. Yeah, there are other artists who paint paleontological reconstructions and whatnot, and Stout's done lots of other wonderful things in his career (like storyboarding Raiders of the Lost Ark, for cryin' out loud!) but to me he's the Dinosaur King.

Anyway, Stout's recollections are kind of harrowing to read, so be warned. Especially the entry about "The Letter." Pro Mike Vosburg turns up with one of his very own after part five. And if you feel your chest tightening, you can always scroll down to the comments where people discuss with Stout some of the more pleasant and beloved personalities in comics-- like the late Jeffrey Catherine Jones and another of my all-time heroes, Al Williamson. And Sergio Aragones, yet another one!

Speaking of-- this is my first time visiting Stout's page, but it won't be the last. I've liked his artwork ever since I read Dinosaur Tales (Bantam Books, 1983), a collection of Ray Bradbury book with some Stout illustrations in it. Some Stout illustrations. As if they were trifles. William Stout is one of the big dinosaur artists of all time. Yeah, there are other artists who paint paleontological reconstructions and whatnot, and Stout's done lots of other wonderful things in his career (like storyboarding Raiders of the Lost Ark, for cryin' out loud!) but to me he's the Dinosaur King.

Anyway, Stout's recollections are kind of harrowing to read, so be warned. Especially the entry about "The Letter." Pro Mike Vosburg turns up with one of his very own after part five. And if you feel your chest tightening, you can always scroll down to the comments where people discuss with Stout some of the more pleasant and beloved personalities in comics-- like the late Jeffrey Catherine Jones and another of my all-time heroes, Al Williamson. And Sergio Aragones, yet another one!

Tuesday, April 2, 2013

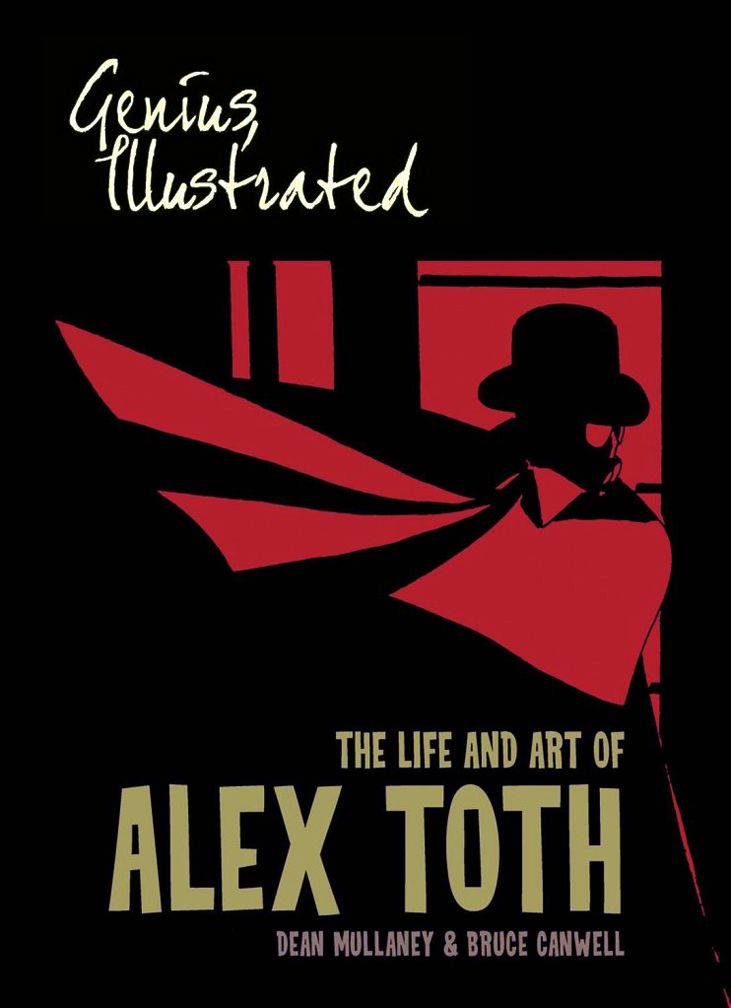

Alex Toth: Genius, Illustrated by Dean Mullaney and Bruce Canwell

Alex Toth: Genius, Illustrated

The Library of American Comics/IDW Publishing, 2013

by Dean Mullaney and Bruce Canwell

You know me as a complete Alex Toth fanatic. There are a number of comic book artists I rate high in my pantheon of gods/goddesses. I don't keep a strict numbering order. One month I'm on a Jack Kirby kick, the next I'm all about Al Williamson, the one following I'm Ai Yazawa's biggest supporter, then it's back to Jaime Hernandez or Steve Rude or Nick Cardy or Rumiko Takahashi or Mike Allred. But out of all of the artists I'm crazy about, the one I most wish I could emulate when I'm drawing is Alex Toth. Many artists add. Crosshatching, little lines here and there. Visual static. Toth subtracted. Melody. His art makes me want to get down to essentials the way he did it-- simplicity, strong silhouettes, interesting camera angles without overdoing it the "Marvel Way," a believability where each element of a plane, airplane or UFO has been thought through and yet reduced to its necessary parts. A face in four lines and a couple of dots. To know what to draw and what to leave out takes study.

The big problem with studying Toth has been the dearth of material to look at. He did a scattering of work for a number of companies and never established a singular body of work at, say, Marvel or DC with a thematic hook where one of those companies could pull it all together in a collected edition. Most of the time when you're exposed to Toth you don't even realize it-- it's on Cartoon Network or Boomerang. Kids of my generation grew up watching Toth's art in action, but crudely animated. For print, he worked at Standard, Warren, Dell, CarToons magazine, Eclipse, Red Circle. Try tracking all that down. If you're lucky, you can find a few Toth gems salted away in a Dark Horse Creepy volume-- but that's paying a lot of money if it's simply Toth you're after (luckily you get Williamson, Frank Frazetta, Gene Colan, Alex Torres, Steve Ditko and Reed Crandall, among others, too)-- or a DC Showcase Presents. But a lot of the other collections are out of print now and cost a fortune on the secondary or even tertiary market.

The two best books have long been Zorro by Alex Toth (Image Comics, 2001) and Setting the Standard: Comics by Alex Toth 1952-1954 (Fantagraphics Books, 2011). Of the two, I prefer Zorro because it's black and white-- with tones he later added himself to correct some lousy coloring provided by Dell-- and so more purely Toth, plus the art is of a somewhat later vintage than his Standard stories and much more characteristic of what I love to look at. Both, however, are required reading for the Toth addict. And now comes this huge, heavy book, the second in a three-volume set covering the entirety of the man's career, a long-overdue monumental biography in prose and art. Toth has finally gotten the examination and treatment he deserves.

Yes, I have the first book, Genius, Isolated. It justly won a Harvey Award, but Genius, Illustrated is even more visually spectacular. If you have to choose between them-- at 49.99 SRP, they're not cheap (although you can probably find a deep-discounted one online)-- then you really must have Genius, Illustrated. Illustrated features more stuff I have an affinity for than Isolated. And a good chunk of it is printed from the originals. Which means you get to see marker fading, brown tape remnants, white correction fluid, non-repro blue and stray graphite pencil marks. It's all oversized, just as before, so Toth's hand is plainly visible in the varying thicknesses of black ink and obvious brush and pen strokes. This is about as close as handling these pages as most of us are likely to come, and they're revelatory. Illustrated covers almost the entirety of Toth's animation career and later period where he created Jesse Bravo, so you'll drool over some of the artist's most personal works, plus rarities you might find surprising.

I mean, I had no idea Toth storyboarded one of my favorite films from when I was a kid, the Hanna-Barbera groaner C.H.O.M.P.S. My childhood collides with my adulthood in an explosive, Jungian way. Not that Jung explodes. I do, with enthusiasm, whenever I encounter this kind of synchronicity. Did I enjoy C.H.O.M.P.S. because I precociously detected something of Toth in it? Or do I enjoy Toth because I loved this shitty movie when I was a kid?

Illustrated contains pages of Toth's superlative Warren work-- I wish someone would do a book devoted entirely to the stories he illustrated for them, but at least you get a decent representation here. You'll also find comic book pieces for other companies strongly represented, with his classic Bob Kanigher "Gallery of War" collaboration, "White Devil...Yellow Devil!," reprinted in its entirety from the original art. Disappointed with the print version, Toth went back and reworked certain panels for clarity. That's how much of a perfectionist he was-- he was also known to rip up entire pages if something struck him as wrong.

And I almost died when I saw for happy reason the authors have included my absolue favorite single page from DC's The Witching Hour, with storyteller Cynthia holding up computer punch-chards, a strong example of Toth's elegant way with anatomy and strong page design. Oh, and in what further confirms me in my raging solipsism, there's even a Jack Kirby drawing inked by Toth which proves the unhappy result of their X-Men #12 (I've been thinking about that one a lot lately) collaboration was a mere bump in the careers of both men. The page they reprint from X-Men features car action, natch. There's also the entirety of his "Steve Bentley, Secret Agent" mock-strip, created for a George Axelrod comedy and starring Jack Lemon.

Because it covers the latter half of Toth's career, which includes multiple stints at Hanna-Barbera and one at Ruby-Spears (Thundarr, my old friend, I'm looking at you... again!), the book gifts us with reams of the master's clean, simple character designs, full-color presentation pieces and provides a master course in Tothian storytelling via his storyboards (similarly, there's an illustrated lecture in a letter to cartoonist Ken Steacy any aspiring comic book artist must read). This period also saw Toth produce an instructive but somewhat stern account of television cartoon production for a Superfriends comic. All this along with with some of his work for the US government-- most notably an anti-rape illustrated essay, the background of which gets to the heart of Toth's problematic relationships with almost everyone.

Because between the artistic glories lies a harrowing tale of a man who was truly his own worst enemy. Putting it mildly, Toth the artist was a genius; Toth the man was sometimes downright ornery.

In the first volume, Mullaney and Canwell quote from journalist/author David Halberstam's passage on Ted Williams, making a completely apt parallel between two men of equal genius in their respective fields but difficult personalities. As the authors note, Halberstam could just as easily have been describing Toth. Funny, because as I read Illustrated, Toth kept reminding me of Williams, who happens to be another hero of mine. Like Williams, Toth was a sensitive man, easily hurt, and his temper was probably a matter of self-defense. I don't know, but you might find something reminiscent about fussin' and a-feudin' Harlan Ellison about Toth. Ellison is referenced by Mullaney and Canwell, disposed of by Toth as a "son of a bitch" in a colorful encounter described in this book.

Along with all the anecdotes from friends and colleagues (cat yronwode, Louise Simonson, Mark Chiarello, John Workman and more), Mullaney and Canwell frequently allow Toth to speak for himself, and demonstrate in ample measure his ability to praise and scold (frequently at the same time!) in passages from personal letters. The most exasperating is the illustrated note he sent Jenette Kahn and Ross Andru where he slaps them around for a paragraph or two over their "inept" handling of DC's Wildcat property, then offers some backhanded praise while suggesting they hire him to do it the right way. Reading that, you're almost in tears, thinking, "Oh no, no, no! What the hell were you thinking, Alex?" Writing himself out of a job, that's what. It stings and wounds the heart.

That's the melancholy power of the story unfolding between reams breath-taking artwork that make up the bulk of Genius, Illustrated. As Toth subtracted the unnecessary from his art, he also subtracted himself from life to a great extent. Having a volcanic temper and a consummate ability to alienate friends, allies and employers certainly did nothing to help his cause, nor did his adherence to aesthetics that were no longer fashionable or trendy. Certainly he saw himself-- and not without justification-- as championing good rendering and storytelling, but there are ways to defend these timeless virtues without going to extremes and belittling the very people you're talking to. Or might hire you. People repeatedly go out of their way to seek out Toth and put him to work, only to have miscommunication and his uncompromising nature sabotage collaboration.

Case in point-- his discussion with Workman at Heavy Metal magazine about doing a comic book adaptation of the Steven Spielberg comedy 1941. The film turned into a noisy mess, and after reading the script, Toth rejected the project outright as disrespectful, but it never seems to have registered with him Workman was actually giving him carte blanche to do whatever he wanted with the characters and setting. He could have gone to to town drawing WWII-era planes and costuming with a brand new story of his own devising and Heavy Metal would have printed it sans interference. An artist's dream. Instead, Toth blew it and left Workman wistful and bemused about how it all went sour.

Temper, timing and personal trials combined to deprive Toth of work and readers of books that would have been instant classics (Simonson tried to get Toth to do an Indian Jones story for Marvel; if that doesn't make your mouth water, then you are reading the wrong blog, buster), but I couldn't help but come away liking him all the more, but sincerely wishing he could have just been a bit more political and less mercurial. But then would he have been Toth? To accept Toth's artwork, we must accept the troubled soul who created it; in this case, the two are entwined. So he wasn't avuncular. Wasn't naturally congenial. Apparently, he could be damned charming when he wanted to and even at his rantiest, there's something vulnerable there you want to embrace, at least given the passage of time. That comes through in Illustrated as well.

With these volumes, Mullaney and Canwell are doing one hell of a job rescuing Toth's life and work and giving both the lavish treatment they deserve. That the authors refuse to give into hagiography and instead present a completely human Toth makes Genius, Illustrated a powerful and heart-breaking tribute to a true genius. Along with Mark Schultz's equally exalting and tragic Al Williamson book, one of the finest volumes on comics I've ever read.

The Library of American Comics/IDW Publishing, 2013

by Dean Mullaney and Bruce Canwell

You know me as a complete Alex Toth fanatic. There are a number of comic book artists I rate high in my pantheon of gods/goddesses. I don't keep a strict numbering order. One month I'm on a Jack Kirby kick, the next I'm all about Al Williamson, the one following I'm Ai Yazawa's biggest supporter, then it's back to Jaime Hernandez or Steve Rude or Nick Cardy or Rumiko Takahashi or Mike Allred. But out of all of the artists I'm crazy about, the one I most wish I could emulate when I'm drawing is Alex Toth. Many artists add. Crosshatching, little lines here and there. Visual static. Toth subtracted. Melody. His art makes me want to get down to essentials the way he did it-- simplicity, strong silhouettes, interesting camera angles without overdoing it the "Marvel Way," a believability where each element of a plane, airplane or UFO has been thought through and yet reduced to its necessary parts. A face in four lines and a couple of dots. To know what to draw and what to leave out takes study.

The big problem with studying Toth has been the dearth of material to look at. He did a scattering of work for a number of companies and never established a singular body of work at, say, Marvel or DC with a thematic hook where one of those companies could pull it all together in a collected edition. Most of the time when you're exposed to Toth you don't even realize it-- it's on Cartoon Network or Boomerang. Kids of my generation grew up watching Toth's art in action, but crudely animated. For print, he worked at Standard, Warren, Dell, CarToons magazine, Eclipse, Red Circle. Try tracking all that down. If you're lucky, you can find a few Toth gems salted away in a Dark Horse Creepy volume-- but that's paying a lot of money if it's simply Toth you're after (luckily you get Williamson, Frank Frazetta, Gene Colan, Alex Torres, Steve Ditko and Reed Crandall, among others, too)-- or a DC Showcase Presents. But a lot of the other collections are out of print now and cost a fortune on the secondary or even tertiary market.

The two best books have long been Zorro by Alex Toth (Image Comics, 2001) and Setting the Standard: Comics by Alex Toth 1952-1954 (Fantagraphics Books, 2011). Of the two, I prefer Zorro because it's black and white-- with tones he later added himself to correct some lousy coloring provided by Dell-- and so more purely Toth, plus the art is of a somewhat later vintage than his Standard stories and much more characteristic of what I love to look at. Both, however, are required reading for the Toth addict. And now comes this huge, heavy book, the second in a three-volume set covering the entirety of the man's career, a long-overdue monumental biography in prose and art. Toth has finally gotten the examination and treatment he deserves.

Yes, I have the first book, Genius, Isolated. It justly won a Harvey Award, but Genius, Illustrated is even more visually spectacular. If you have to choose between them-- at 49.99 SRP, they're not cheap (although you can probably find a deep-discounted one online)-- then you really must have Genius, Illustrated. Illustrated features more stuff I have an affinity for than Isolated. And a good chunk of it is printed from the originals. Which means you get to see marker fading, brown tape remnants, white correction fluid, non-repro blue and stray graphite pencil marks. It's all oversized, just as before, so Toth's hand is plainly visible in the varying thicknesses of black ink and obvious brush and pen strokes. This is about as close as handling these pages as most of us are likely to come, and they're revelatory. Illustrated covers almost the entirety of Toth's animation career and later period where he created Jesse Bravo, so you'll drool over some of the artist's most personal works, plus rarities you might find surprising.

I mean, I had no idea Toth storyboarded one of my favorite films from when I was a kid, the Hanna-Barbera groaner C.H.O.M.P.S. My childhood collides with my adulthood in an explosive, Jungian way. Not that Jung explodes. I do, with enthusiasm, whenever I encounter this kind of synchronicity. Did I enjoy C.H.O.M.P.S. because I precociously detected something of Toth in it? Or do I enjoy Toth because I loved this shitty movie when I was a kid?

Illustrated contains pages of Toth's superlative Warren work-- I wish someone would do a book devoted entirely to the stories he illustrated for them, but at least you get a decent representation here. You'll also find comic book pieces for other companies strongly represented, with his classic Bob Kanigher "Gallery of War" collaboration, "White Devil...Yellow Devil!," reprinted in its entirety from the original art. Disappointed with the print version, Toth went back and reworked certain panels for clarity. That's how much of a perfectionist he was-- he was also known to rip up entire pages if something struck him as wrong.

And I almost died when I saw for happy reason the authors have included my absolue favorite single page from DC's The Witching Hour, with storyteller Cynthia holding up computer punch-chards, a strong example of Toth's elegant way with anatomy and strong page design. Oh, and in what further confirms me in my raging solipsism, there's even a Jack Kirby drawing inked by Toth which proves the unhappy result of their X-Men #12 (I've been thinking about that one a lot lately) collaboration was a mere bump in the careers of both men. The page they reprint from X-Men features car action, natch. There's also the entirety of his "Steve Bentley, Secret Agent" mock-strip, created for a George Axelrod comedy and starring Jack Lemon.

Because it covers the latter half of Toth's career, which includes multiple stints at Hanna-Barbera and one at Ruby-Spears (Thundarr, my old friend, I'm looking at you... again!), the book gifts us with reams of the master's clean, simple character designs, full-color presentation pieces and provides a master course in Tothian storytelling via his storyboards (similarly, there's an illustrated lecture in a letter to cartoonist Ken Steacy any aspiring comic book artist must read). This period also saw Toth produce an instructive but somewhat stern account of television cartoon production for a Superfriends comic. All this along with with some of his work for the US government-- most notably an anti-rape illustrated essay, the background of which gets to the heart of Toth's problematic relationships with almost everyone.

Because between the artistic glories lies a harrowing tale of a man who was truly his own worst enemy. Putting it mildly, Toth the artist was a genius; Toth the man was sometimes downright ornery.

In the first volume, Mullaney and Canwell quote from journalist/author David Halberstam's passage on Ted Williams, making a completely apt parallel between two men of equal genius in their respective fields but difficult personalities. As the authors note, Halberstam could just as easily have been describing Toth. Funny, because as I read Illustrated, Toth kept reminding me of Williams, who happens to be another hero of mine. Like Williams, Toth was a sensitive man, easily hurt, and his temper was probably a matter of self-defense. I don't know, but you might find something reminiscent about fussin' and a-feudin' Harlan Ellison about Toth. Ellison is referenced by Mullaney and Canwell, disposed of by Toth as a "son of a bitch" in a colorful encounter described in this book.

Along with all the anecdotes from friends and colleagues (cat yronwode, Louise Simonson, Mark Chiarello, John Workman and more), Mullaney and Canwell frequently allow Toth to speak for himself, and demonstrate in ample measure his ability to praise and scold (frequently at the same time!) in passages from personal letters. The most exasperating is the illustrated note he sent Jenette Kahn and Ross Andru where he slaps them around for a paragraph or two over their "inept" handling of DC's Wildcat property, then offers some backhanded praise while suggesting they hire him to do it the right way. Reading that, you're almost in tears, thinking, "Oh no, no, no! What the hell were you thinking, Alex?" Writing himself out of a job, that's what. It stings and wounds the heart.

That's the melancholy power of the story unfolding between reams breath-taking artwork that make up the bulk of Genius, Illustrated. As Toth subtracted the unnecessary from his art, he also subtracted himself from life to a great extent. Having a volcanic temper and a consummate ability to alienate friends, allies and employers certainly did nothing to help his cause, nor did his adherence to aesthetics that were no longer fashionable or trendy. Certainly he saw himself-- and not without justification-- as championing good rendering and storytelling, but there are ways to defend these timeless virtues without going to extremes and belittling the very people you're talking to. Or might hire you. People repeatedly go out of their way to seek out Toth and put him to work, only to have miscommunication and his uncompromising nature sabotage collaboration.

Case in point-- his discussion with Workman at Heavy Metal magazine about doing a comic book adaptation of the Steven Spielberg comedy 1941. The film turned into a noisy mess, and after reading the script, Toth rejected the project outright as disrespectful, but it never seems to have registered with him Workman was actually giving him carte blanche to do whatever he wanted with the characters and setting. He could have gone to to town drawing WWII-era planes and costuming with a brand new story of his own devising and Heavy Metal would have printed it sans interference. An artist's dream. Instead, Toth blew it and left Workman wistful and bemused about how it all went sour.

Temper, timing and personal trials combined to deprive Toth of work and readers of books that would have been instant classics (Simonson tried to get Toth to do an Indian Jones story for Marvel; if that doesn't make your mouth water, then you are reading the wrong blog, buster), but I couldn't help but come away liking him all the more, but sincerely wishing he could have just been a bit more political and less mercurial. But then would he have been Toth? To accept Toth's artwork, we must accept the troubled soul who created it; in this case, the two are entwined. So he wasn't avuncular. Wasn't naturally congenial. Apparently, he could be damned charming when he wanted to and even at his rantiest, there's something vulnerable there you want to embrace, at least given the passage of time. That comes through in Illustrated as well.

With these volumes, Mullaney and Canwell are doing one hell of a job rescuing Toth's life and work and giving both the lavish treatment they deserve. That the authors refuse to give into hagiography and instead present a completely human Toth makes Genius, Illustrated a powerful and heart-breaking tribute to a true genius. Along with Mark Schultz's equally exalting and tragic Al Williamson book, one of the finest volumes on comics I've ever read.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)