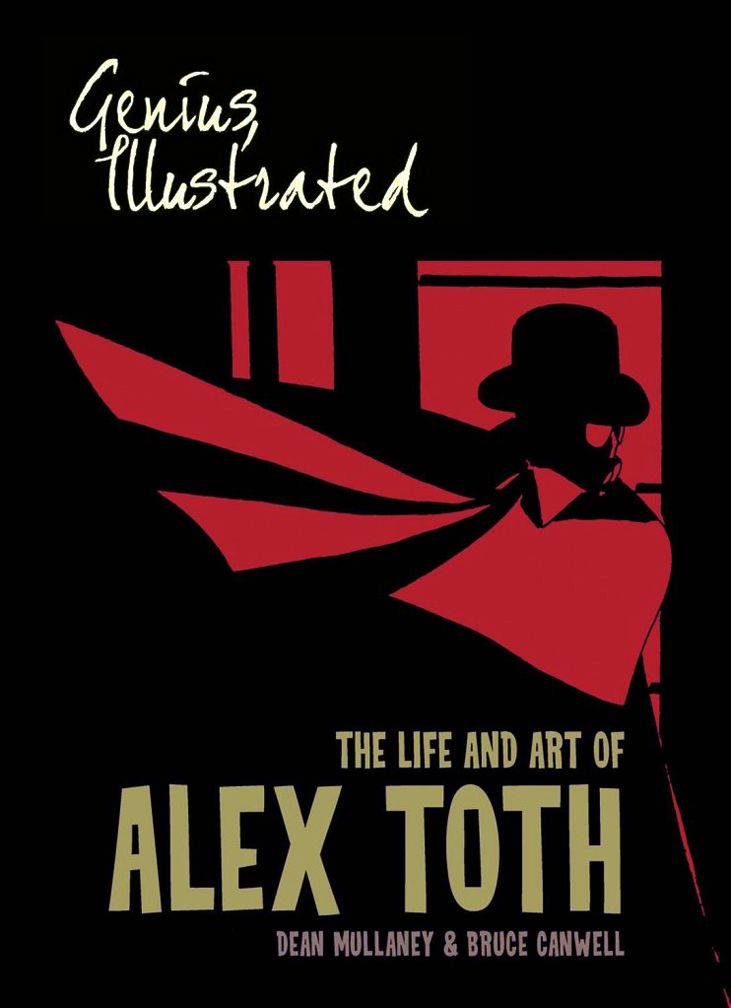

Alex Toth: Genius, Illustrated

The Library of American Comics/IDW Publishing, 2013

by Dean Mullaney and Bruce Canwell

You know me as a complete Alex Toth fanatic. There are a number of comic book artists I rate high in my pantheon of gods/goddesses. I don't keep a strict numbering order. One month I'm on a Jack Kirby kick, the next I'm all about Al Williamson, the one following I'm Ai Yazawa's biggest supporter, then it's back to Jaime Hernandez or Steve Rude or Nick Cardy or Rumiko Takahashi or Mike Allred. But out of all of the artists I'm crazy about, the one I most wish I could emulate when I'm drawing is Alex Toth. Many artists add. Crosshatching, little lines here and there. Visual static. Toth subtracted. Melody. His art makes me want to get down to essentials the way he did it-- simplicity, strong silhouettes, interesting camera angles without overdoing it the "Marvel Way," a believability where each element of a plane, airplane or UFO has been thought through and yet reduced to its necessary parts. A face in four lines and a couple of dots. To know what to draw and what to leave out takes study.

The big problem with studying Toth has been the dearth of material to look at. He did a scattering of work for a number of companies and never established a singular body of work at, say, Marvel or DC with a thematic hook where one of those companies could pull it all together in a collected edition. Most of the time when you're exposed to Toth you don't even realize it-- it's on Cartoon Network or Boomerang. Kids of my generation grew up watching Toth's art in action, but crudely animated. For print, he worked at Standard, Warren, Dell, CarToons magazine, Eclipse, Red Circle. Try tracking all that down. If you're lucky, you can find a few Toth gems salted away in a Dark Horse Creepy volume-- but that's paying a lot of money if it's simply Toth you're after (luckily you get Williamson, Frank Frazetta, Gene Colan, Alex Torres, Steve Ditko and Reed Crandall, among others, too)-- or a DC Showcase Presents. But a lot of the other collections are out of print now and cost a fortune on the secondary or even tertiary market.

The two best books have long been Zorro by Alex Toth (Image Comics, 2001) and Setting the Standard: Comics by Alex Toth 1952-1954 (Fantagraphics Books, 2011). Of the two, I prefer Zorro because it's black and white-- with tones he later added himself to correct some lousy coloring provided by Dell-- and so more purely Toth, plus the art is of a somewhat later vintage than his Standard stories and much more characteristic of what I love to look at. Both, however, are required reading for the Toth addict. And now comes this huge, heavy book, the second in a three-volume set covering the entirety of the man's career, a long-overdue monumental biography in prose and art. Toth has finally gotten the examination and treatment he deserves.

Yes, I have the first book, Genius, Isolated. It justly won a Harvey Award, but Genius, Illustrated is even more visually spectacular. If you have to choose between them-- at 49.99 SRP, they're not cheap (although you can probably find a deep-discounted one online)-- then you really must have Genius, Illustrated. Illustrated features more stuff I have an affinity for than Isolated. And a good chunk of it is printed from the originals. Which means you get to see marker fading, brown tape remnants, white correction fluid, non-repro blue and stray graphite pencil marks. It's all oversized, just as before, so Toth's hand is plainly visible in the varying thicknesses of black ink and obvious brush and pen strokes. This is about as close as handling these pages as most of us are likely to come, and they're revelatory. Illustrated covers almost the entirety of Toth's animation career and later period where he created Jesse Bravo, so you'll drool over some of the artist's most personal works, plus rarities you might find surprising.

I mean, I had no idea Toth storyboarded one of my favorite films from when I was a kid, the Hanna-Barbera groaner C.H.O.M.P.S. My childhood collides with my adulthood in an explosive, Jungian way. Not that Jung explodes. I do, with enthusiasm, whenever I encounter this kind of synchronicity. Did I enjoy C.H.O.M.P.S. because I precociously detected something of Toth in it? Or do I enjoy Toth because I loved this shitty movie when I was a kid?

Illustrated contains pages of Toth's superlative Warren work-- I wish someone would do a book devoted entirely to the stories he illustrated for them, but at least you get a decent representation here. You'll also find comic book pieces for other companies strongly represented, with his classic Bob Kanigher "Gallery of War" collaboration, "White Devil...Yellow Devil!," reprinted in its entirety from the original art. Disappointed with the print version, Toth went back and reworked certain panels for clarity. That's how much of a perfectionist he was-- he was also known to rip up entire pages if something struck him as wrong.

And I almost died when I saw for happy reason the authors have included my absolue favorite single page from DC's The Witching Hour, with storyteller Cynthia holding up computer punch-chards, a strong example of Toth's elegant way with anatomy and strong page design. Oh, and in what further confirms me in my raging solipsism, there's even a Jack Kirby drawing inked by Toth which proves the unhappy result of their X-Men #12 (I've been thinking about that one a lot lately) collaboration was a mere bump in the careers of both men. The page they reprint from X-Men features car action, natch. There's also the entirety of his "Steve Bentley, Secret Agent" mock-strip, created for a George Axelrod comedy and starring Jack Lemon.

Because it covers the latter half of Toth's career, which includes multiple stints at Hanna-Barbera and one at Ruby-Spears (Thundarr, my old friend, I'm looking at you... again!), the book gifts us with reams of the master's clean, simple character designs, full-color presentation pieces and provides a master course in Tothian storytelling via his storyboards (similarly, there's an illustrated lecture in a letter to cartoonist Ken Steacy any aspiring comic book artist must read). This period also saw Toth produce an instructive but somewhat stern account of television cartoon production for a Superfriends comic. All this along with with some of his work for the US government-- most notably an anti-rape illustrated essay, the background of which gets to the heart of Toth's problematic relationships with almost everyone.

Because between the artistic glories lies a harrowing tale of a man who was truly his own worst enemy. Putting it mildly, Toth the artist was a genius; Toth the man was sometimes downright ornery.

In the first volume, Mullaney and Canwell quote from journalist/author David Halberstam's passage on Ted Williams, making a completely apt parallel between two men of equal genius in their respective fields but difficult personalities. As the authors note, Halberstam could just as easily have been describing Toth. Funny, because as I read Illustrated, Toth kept reminding me of Williams, who happens to be another hero of mine. Like Williams, Toth was a sensitive man, easily hurt, and his temper was probably a matter of self-defense. I don't know, but you might find something reminiscent about fussin' and a-feudin' Harlan Ellison about Toth. Ellison is referenced by Mullaney and Canwell, disposed of by Toth as a "son of a bitch" in a colorful encounter described in this book.

Along with all the anecdotes from friends and colleagues (cat yronwode, Louise Simonson, Mark Chiarello, John Workman and more), Mullaney and Canwell frequently allow Toth to speak for himself, and demonstrate in ample measure his ability to praise and scold (frequently at the same time!) in passages from personal letters. The most exasperating is the illustrated note he sent Jenette Kahn and Ross Andru where he slaps them around for a paragraph or two over their "inept" handling of DC's Wildcat property, then offers some backhanded praise while suggesting they hire him to do it the right way. Reading that, you're almost in tears, thinking, "Oh no, no, no! What the hell were you thinking, Alex?" Writing himself out of a job, that's what. It stings and wounds the heart.

That's the melancholy power of the story unfolding between reams breath-taking artwork that make up the bulk of Genius, Illustrated. As Toth subtracted the unnecessary from his art, he also subtracted himself from life to a great extent. Having a volcanic temper and a consummate ability to alienate friends, allies and employers certainly did nothing to help his cause, nor did his adherence to aesthetics that were no longer fashionable or trendy. Certainly he saw himself-- and not without justification-- as championing good rendering and storytelling, but there are ways to defend these timeless virtues without going to extremes and belittling the very people you're talking to. Or might hire you. People repeatedly go out of their way to seek out Toth and put him to work, only to have miscommunication and his uncompromising nature sabotage collaboration.

Case in point-- his discussion with Workman at Heavy Metal magazine about doing a comic book adaptation of the Steven Spielberg comedy 1941. The film turned into a noisy mess, and after reading the script, Toth rejected the project outright as disrespectful, but it never seems to have registered with him Workman was actually giving him carte blanche to do whatever he wanted with the characters and setting. He could have gone to to town drawing WWII-era planes and costuming with a brand new story of his own devising and Heavy Metal would have printed it sans interference. An artist's dream. Instead, Toth blew it and left Workman wistful and bemused about how it all went sour.

Temper, timing and personal trials combined to deprive Toth of work and readers of books that would have been instant classics (Simonson tried to get Toth to do an Indian Jones story for Marvel; if that doesn't make your mouth water, then you are reading the wrong blog, buster), but I couldn't help but come away liking him all the more, but sincerely wishing he could have just been a bit more political and less mercurial. But then would he have been Toth? To accept Toth's artwork, we must accept the troubled soul who created it; in this case, the two are entwined. So he wasn't avuncular. Wasn't naturally congenial. Apparently, he could be damned charming when he wanted to and even at his rantiest, there's something vulnerable there you want to embrace, at least given the passage of time. That comes through in Illustrated as well.

With these volumes, Mullaney and Canwell are doing one hell of a job rescuing Toth's life and work and giving both the lavish treatment they deserve. That the authors refuse to give into hagiography and instead present a completely human Toth makes Genius, Illustrated a powerful and heart-breaking tribute to a true genius. Along with Mark Schultz's equally exalting and tragic Al Williamson book, one of the finest volumes on comics I've ever read.

No comments:

Post a Comment