Wednesday, January 8, 2014

Kamandi #20 (August 1974): This is the image that made me a Kirby fan for life!

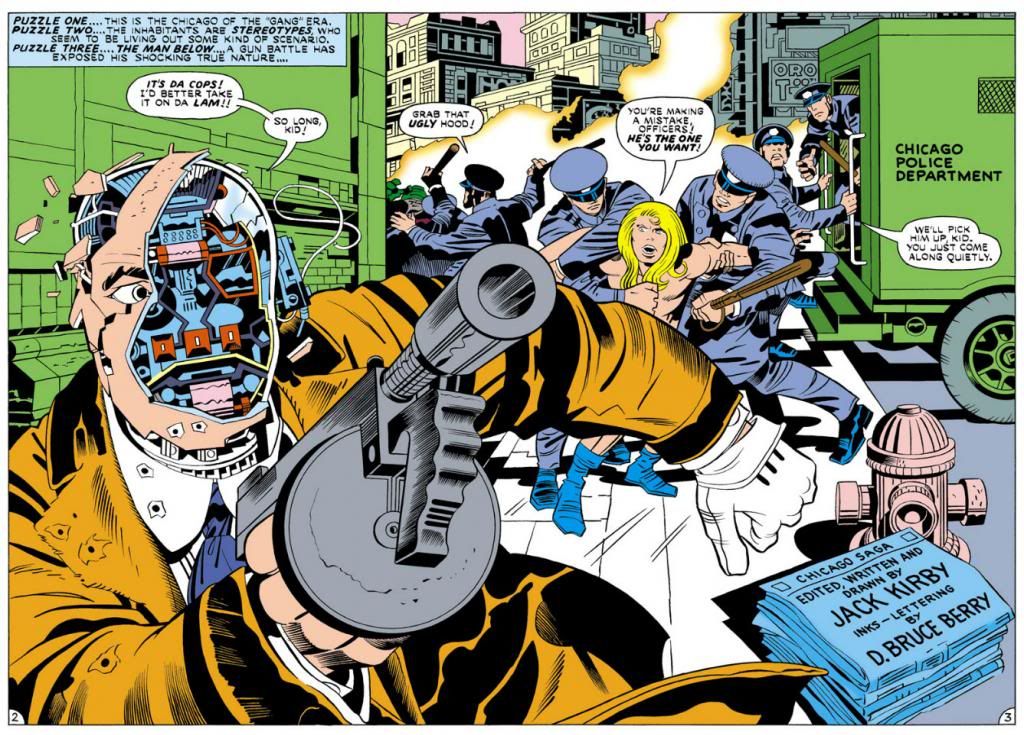

Here's a double-page spread from Kamandi #20 (August 1974), the first Kirby comic I ever owned. I've already talked about that issue at some length here, and I'm sure you were fascinated by my commentary. It's here again because a black and white version popped up on Facebook and I was struck by its personal significance to me as a comics fan, and also because a big name professional clued everyone into something peculiar about it. Can you guess what it is?

That's right! Perspective!

Did you notice how nutty the perspective is in this drawing? Despite having studied art at a major university (I learned nothing because I'm an idiot), I never particularly gave it much thought until that pro pointed it out. As he also commented, despite the crazy perspective (or maybe even because of it), the image still works. Unless you make a living drawing this stuff everyday, or you're a lot smarter than I am, you probably wouldn't give two farts whether or not Kirby gets all the receding lines going to the correct vanishing points or not. And even if you do give those two farts, the important thing is whether or not this image has impact and makes story sense. It does!

What we glean from it, the most important information Kirby provides, is the shocking revelation that this tommy gun toting mobster is a robot. With such a wild and wooly concatenation of figures and a startling storytelling moment, the focal points are that robot face and Kamandi's reaction. This moment takes place during a police riot, which provides not only context but also a lot of energy and movement, like a similarly staged fight scene in a movie. Spartacus, for example.

Notice how you're reading from left to right, so your eye goes right from the gangster's shattered visage to Kamandi's wide-eyed reaction. The barrel of the machine gun, despite ostensibly being aimed somewhere over the reader's shoulder (involving YOU in the danger!), also serves to point to Kamandi. The foreground is an eyeballed one-point perspective. The lines on the green building on the left do not go to the same vanishing point as the ones on the paddy wagon on the right. But they do serve to draw the eye back to Kamandi, creating a zoom effect within a single panel. And check out the angle on that sidewalk. Where is it heading? The background mob hides its destination, but if we follow it, we'll actually end about halfway up one of those buildings in the distant background, the ones Kirby partially obscures with flames-- and which are drawn in two-point perspective!

I'd also suggest the faked perspective adds to the drunken, dreamlike quality here, on a subconscious level for the average reader (like me). Kamandi, with his long, feminine blonde hair, is reminiscent of Alice from the Lewis Carroll stories, or at least the various Sir John Tenniel-derived versions that form our mental impression of her. Carroll played games with language, math and logic in his prose, and Kirby does something similar with his visuals. Kamandi, like Alice, takes an at-times rather nasty, almost psychedelic, trip through a land of talking animals, where reason and rational thought are overturned or inverted in favor of nonsense. So it's appropriate for vanishing points and perspective planes to play tricks on our perception. Kirby helps it along by having the figures relate to each other proportionally and because they seem to be standing on roughly the same plane. Their environment may be illogical, but they, for the most part, are not.

The end result is a magnificent expressionist image that conveys dynamic action and provides more thrills than any six Hollywood summer blockbusters you could name. It's also just a really cool picture.

And it's the coolness of it all that made me love Jack Kirby's work. That, and the talking gorillas.

Labels:

DC Comics,

great art,

Jack Kirby,

John Tenniel,

Kamandi,

vintage comics

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment