And, I hope, cause you to buy this book.

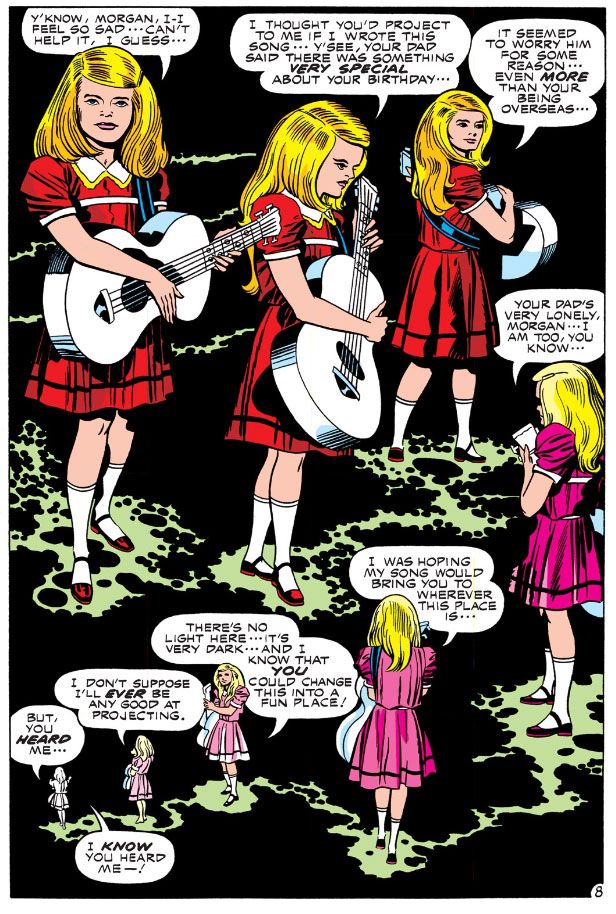

Kirby starts with a panel-free backgroundless sequence as Tracy Coleman, a young girl with a guitar, prepares to play a birthday song she’s written. By dispensing with both panels and backgrounds Kirby liberates this moment from the more concrete reality of the narrative-driven panel-bordered pages. This takes place outside time, within the mental realm, and Kirby uses his imaginary camera's eye to circle the girl in a dreamy, clockwise direction and a slow zoom to close-up, and careful placement of word balloons and a kind of sparkly path to direct the reader sequentially. The in-story reason for all these effects is Tracy isn't simply performing a song, she's also “reaching out,” or attempting telepathic contact with Morgan Miller, the titular character. Kirby allows the readers to float ever closer to Tracy's face as if we're a ghostly presence, zooming in there in the lower right-hand corner in order to set up a spatial change with the turn of the page.

|

| Kirby with Mike Royer |

On the next page, we are back in the "real world," where the sequence is ordered by the traditional black panel borders and white gutter spaces. Here we discover Morgan is in

combat in Vietnam, fighting the very battle where he'll win the medal that provides him with his superhero codename and this comic its title. Conventional narrative

boxes contain the girl’s words, a simple celebratory verse. Juxtapositioning this song and its simple, straight-forward celebration of birth and life with dynamic visuals of

chaotic violence and death allows Kirby to achieve an emotional effect, with the song functioning as a critique of the adult world and its adherence to destruction.

This is the comic book equivalent of Carl Foreman's use of sentimental Christmas songs on the soundtrack while GIs are trucked through the snow to witness a prisoner’s execution by firing squad in his 1963 war film The Victors. The tragic commentary is similar, but Kirby isn’t exploiting sentimentality to make a cynical point. The contrast here is in complete sincerity, the girl’s wistful song representing the purity of love as only an innocent can express it, the combat displaying the worst of which we’re capable of once experienced in the ways of the world.

This is the comic book equivalent of Carl Foreman's use of sentimental Christmas songs on the soundtrack while GIs are trucked through the snow to witness a prisoner’s execution by firing squad in his 1963 war film The Victors. The tragic commentary is similar, but Kirby isn’t exploiting sentimentality to make a cynical point. The contrast here is in complete sincerity, the girl’s wistful song representing the purity of love as only an innocent can express it, the combat displaying the worst of which we’re capable of once experienced in the ways of the world.

|

| Kirby/Royer |

This kind of "flesh-against-steel" pitched battle imagery strikes me as more WWII than

Vietnam, though, the sort of desperate combat action Kirby was intimately acquainted with from his service as a scout in the 5th Infantry Division in 1944. I’m not sure how often

American troops came up against North Vietnamese armor in Vietnam. I did some research today and could only find some scant references to our tanks blasting a couple of PT-76s (a Soviet-built amphibious tank) and a BTR-50 at Ben Het in early March 1969. The enemy tanks in Silver Star appear to be a Kirby-version of the Soviet T-34, a WWII-era design which the NVA had in stock. There’s a

reason Kirby deploys enemy armor and it has to do with genetic mutation and

superhuman strength, which we see as the fighting reaches its climax: it's scary and effective! In his most desperate moment, Morgan Miller experiences a battlefield transformation into something more than human.

I can't help but wonder if the scene where he tosses a T-34 as if it were a football had its origin in some of Kirby's own fantasies born while facing down Wehrmacht tanks. GIs probably wished they could turn into nigh-invulnerable superman in times like that.

Note the wild special effects in the fourth panel as Morgan's mutational powers activate themselves. This is the Kirby equivalent of solarized photographic imagery of the sort we've seen during the "psychedelic" mind-warp climax to Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey. Only in Kirby's usage, the cosmos that create an evolutionary leap are contained within the individual, rather than as an external force. It's worth noting Kirby adapted Kubrick's film for Marvel a few years prior to working on Silver Star.

I can't help but wonder if the scene where he tosses a T-34 as if it were a football had its origin in some of Kirby's own fantasies born while facing down Wehrmacht tanks. GIs probably wished they could turn into nigh-invulnerable superman in times like that.

Note the wild special effects in the fourth panel as Morgan's mutational powers activate themselves. This is the Kirby equivalent of solarized photographic imagery of the sort we've seen during the "psychedelic" mind-warp climax to Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey. Only in Kirby's usage, the cosmos that create an evolutionary leap are contained within the individual, rather than as an external force. It's worth noting Kirby adapted Kubrick's film for Marvel a few years prior to working on Silver Star.

Afterwards, Kirby cuts back to Tracy and her borderless dark space, the

area of the mind. We drift away from her, circling clockwise once more but slowly zooming out as she shrinks away in the left-hand corner to end the sequence.

|

| Kirby/Royer |

That in itself is unusual, since we're used to reading comics in a Z-pattern, left-to-right and this is an S. The top tier proceeds along the expected direction, but then Kirby reverses flow for the lower tier. Ending the page on the left is counter to our long-established Western reading mode. It only adds to the dreamlike unreality of the framing pages, but Kirby keeps things under control and avoids confusion. It's very easy to follow this flow.

Image Comics has made Jack Kirby's original Silver Star six-issue series available on Comixology. I believe there's a print version as well. While I had a few issues of Captain Victory and his Galactic Rangers, for some reason I don't think I ever bought Silver Star. Very odd, since I enjoyed Captain Victory and was a big supporter of everything Pacific put out back in the 1980s. It probably had something to do with economics, since these comics were one dollar at a time when others were half that price. And also the ephemerality of comic book shops in my hometown. Two came and went in just about the time it takes you to finish reading this sentence!

No comments:

Post a Comment