Well, if you're doing a comic book version of a war movie about airplanes with John Wayne as the lead, you couldn't ask for a better artist than Alex Toth. Here he tackles the 1957 John Ford film The Wings of Eagles (Dell Four Color #790, April 1957). As far as I can remember, I haven't seen this movie, but after reading the comic, I'm thinking this is the kind of movie that doesn't innovate in an attempt to get at the inner desires and struggled of its subject, but just aims to please audiences with a rousing action story tribute to a guy who hobbled himself by accident but still went to war because he was so damned patriotic. A guy who just happened to have been good friends with the director himself.

Frank "Spig" Wead's life story kind of boggles the imagination and my first impression was, "No way." I mean, John Wayne as a hard-brawling guy named Spig?

But I did a little reading and I was wrong. While the photo I saw looks absolutely nothing like Wayne (a young David Strathairn comes immediately to mind), the real Wead actually was a pioneer of Naval aviation and carrier operations and part of a Navy flight team that won the Schneider Cup in 1923. Then he fell and broke his neck one night. Forced to retire from the Navy, Wead turned to expressing himself through writing and scripted films, mostly having to do with the military and flying. His film work netted him two Academy Award nominations. During WWII, Wead returned to service, helped develop the idea of the escort carrier (called "jeep" carriers in this comic), and even managed some sea duty aboard the carriers USS Yorktown and Essex.

Still, I can't help but think John Wayne was miscast in this film, or that Ford and company altered reality just a smidge to fit it to his oversized shoulders. While he certainly beat the drum as a patriot (despite not having actually put on a uniform in earnest), I simply can't imagine Wayne as a writer of any kind, military or not. Or hobbling around on crutches. If this Dell adaptation is accurate to the movie at all, it seems your typical mix of fact and Hollywood hokum... er... dramatic license, with events simplified and telescoped, secondary characters invented or composited. There's a thinly-disguised Ford stand-in played by Ward Bond. They call him John Dodge (clever, boys, clever!). There's a guy apparently based on Billy Mitchell who constantly fights with Wead (Toth depicts Wayne in the aftermath of these moments with cute little bandages on his face), which probably owes more to Flagg and Quirt from What Price Glory? than either Wead's or Mitchell's lives. There's a guy named Jughead, for chrissake! Even the film's title is a bit of a groaner.

But, as I said, I haven't seen it and there's always the Ford factor. Discount even a minor Ford film at your peril, and this one came in the wake of his superlative Western The Searchers. Whatever the quality of the movie it's based on, the book itself is aces, a little slice of perfection. Toth himself appears to have been thoroughly engaged by the material and just knocks himself out. He gets to draw airplanes from multiple eras and even a big time Hollywood movie premiere with 1930s-style cars. It's in the acting-- as well as the action-- that Toth really shines in this outing.

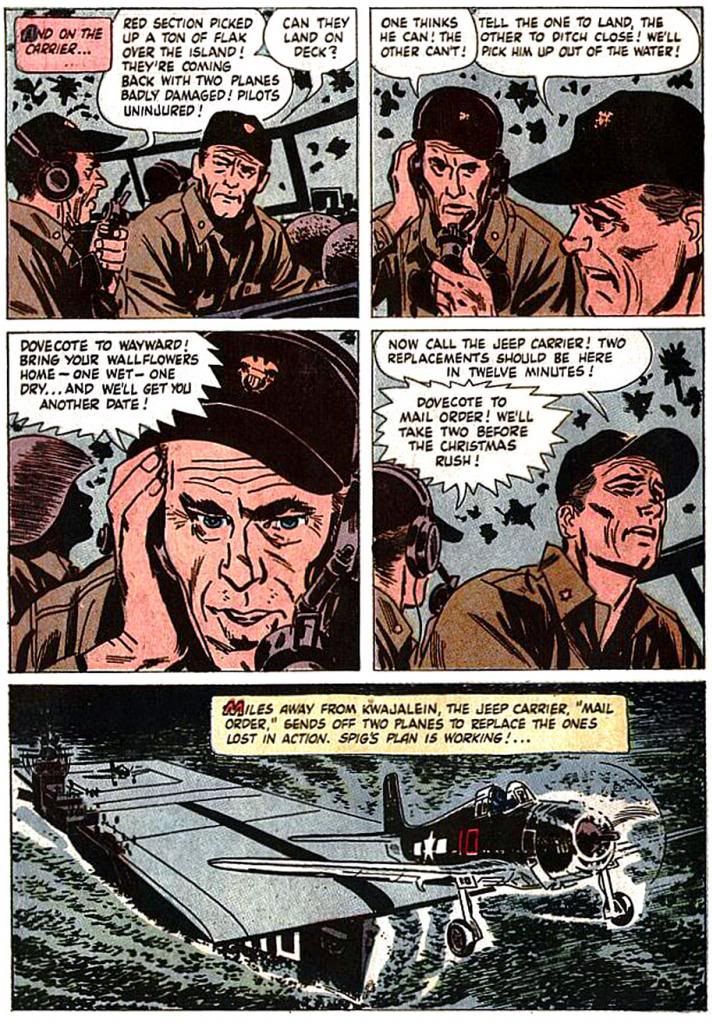

Here he pulls out the stops with unique facial expressions, really bringing the characters to life. His Wead/Wayne may not look a whole lot like the Duke-- other than matching him for imposing size compared to everyone else on the page-- but Toth nails the man's broad acting style. Even in scenes where the action is largely internal-- Wead struggles with writing inspiration and later, with the problem of prolonging carrier operations during invasions despite attrition in aircraft and men, Toth adds interest by choosing the right angle, the right facial expression. He once remarked something to the effect that some talky scenes will be by their very nature pedestrian, but he avoids that trap here. Or maybe it's just that the comedic drunken brawling and daredevil flying stuff more than make up for the internalized moments.

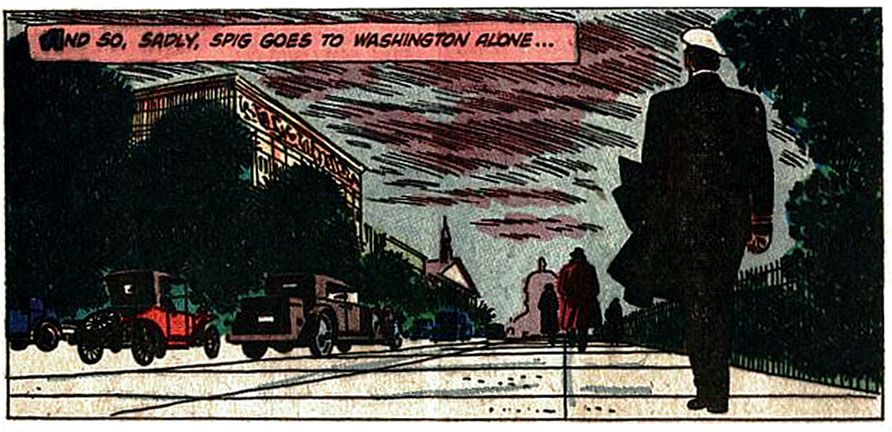

Despite the usual crap printing of the day, it's obvious even the coloring job is well thought-out. It uses a muted color scheme largely in various tints of blue, probably because so much of it takes place either in the air or on the sea. The colors don't exactly pop, but they're not garish nor do they battle Toth's line work. Check out this moody twilight scene:

Now we've all seen 1950s-era war flicks. They almost always save a bit of money by using stock footage. Authentic, but it's usually so glaringly obvious it throws me right out of the story. It also makes me wish I was simply watching a documentary so I can properly consider the millions of real people who died in pain and terror without the unfortunate context of their sacrifice serving to make John Wayne look like a great guy up on the silver screen. War comics of this era by their very nature-- generally aimed at kids-- tend to turn it all into a grand spectacle, with manly dogfaces stoically facing death or wisecracking their way through battles depending on the story's whims, largely sanitized to suit the Comics Code. Eagles is at least based on actual events, and Toth is untrammeled by budget considerations, so when he depicts life aboard a flattop doing its deadly business out there in the Pacific, we can imagine it's the real thing and not some rear-projected footage on a soundstage in Los Angeles.

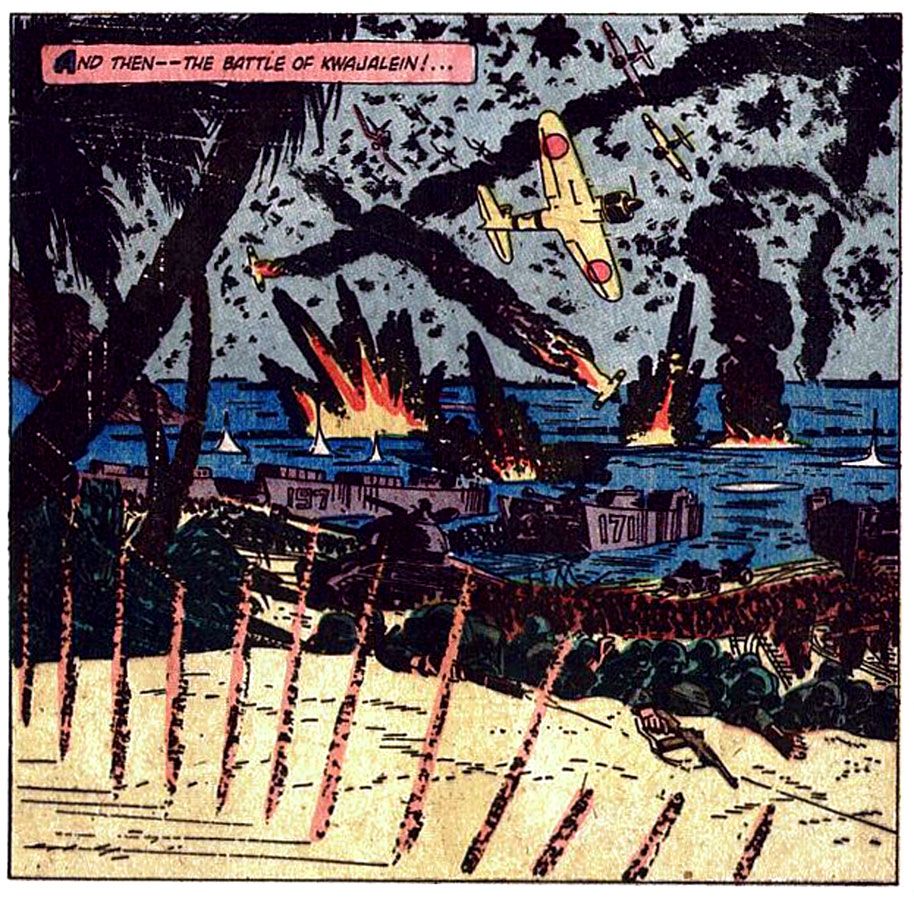

His major battle scene in the book is a single over-sized panel that's practically a whole school on controlling eye movement and presenting depth in itself. In the foreground, there are machine gun strikes, then a middle-ground plane made up of palm trees and the invasion force itself, with troops and a tank largely suggested through silhouetting, a bright flash of a Zero overhead drawing our gaze upward into the background, a sky Toth speckles with angry ink blotches representing flak. It's appropriately hectic and violent, certainly doesn't look like fun for Gunner and Sarge. Toth compresses a whole day's worth of death and destruction into this single image.

This is contrasted on the next page by some talking heads which bring us back into the story proper and provide tension. Then, another incredible panel of a Wildcat taking off, reminding us of the scope of the day's events and showing us Spig's grand idea coming to fruition.

I can't imagine Ford-- unlike Wayne, Ford knew war first-hand, having been wounded at Midway and present on Omaha Beach itself during the D-Day invasion-- reading this and feeling his cinematic vision slighted. This is some sterling Toth, and really deserves another look. Fortunately, you can find the whole thing online at a couple of different blogs to enjoy for yourself.

Monday, July 29, 2013

Sunday, July 28, 2013

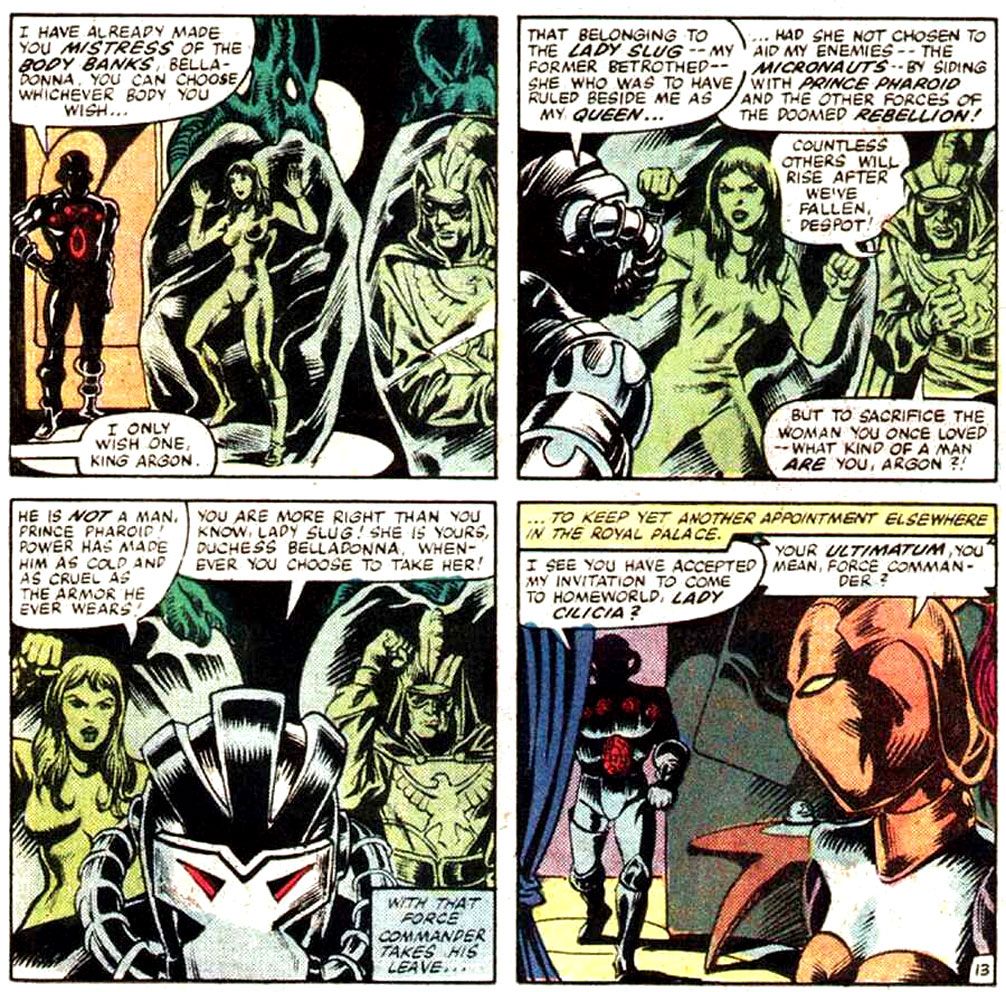

In Which We Sing of Slug

In writing Marvel's Micronauts series, Bill Mantlo took a toy line with no narrative and gave it one, set in a sub-atomic universe filled with all sorts of settings and characters. As the toys touted their "interchangeability," so too did Mantlo assemble the comic out of various parts-- a little Flash Gordon, some Kirby Fourth World, a bit of Star Wars (which I think is obvious and certainly no crime, though Mantlo denied it forcefully in a letter page response to a reader who pointed it out-- to be fair, let's just say Mantlo and Lucas drew from the same source material). To this rich mix he added some cool flourishes that give Micronauts its own identity. Acroyear, for example, was merely the name of two of the toy bad guys, but Mantlo created an entire race of honorable warrior Acroyear, led by a noble outcast who became a major player on the Micronauts team. This innovation came a few years before Star Trek: The Next Generation reconfigured the Klingons from crudely-motivated space cossacks into a clan-and-honor-based culture drawing from Japanese martial tradition. Mantlo also came up with a lot of interesting little supporting characters, too—characters like rebel leader Slug.

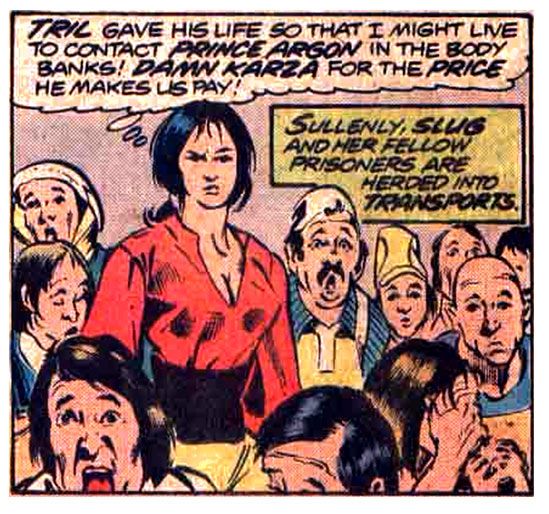

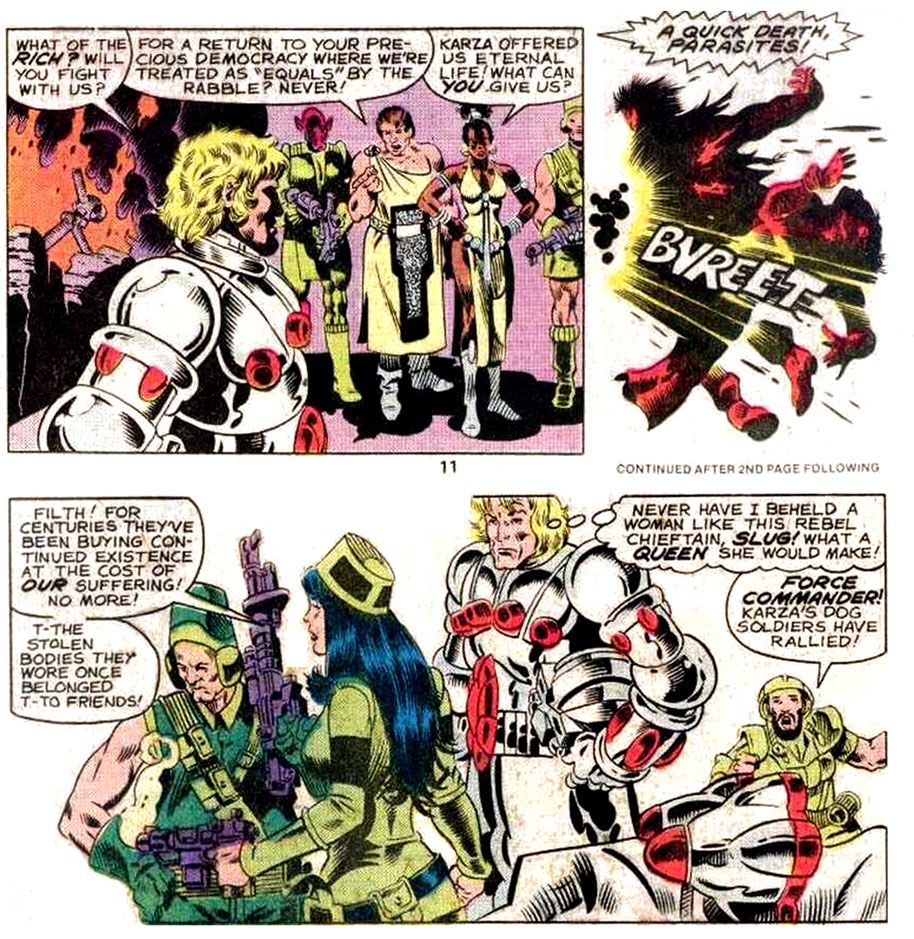

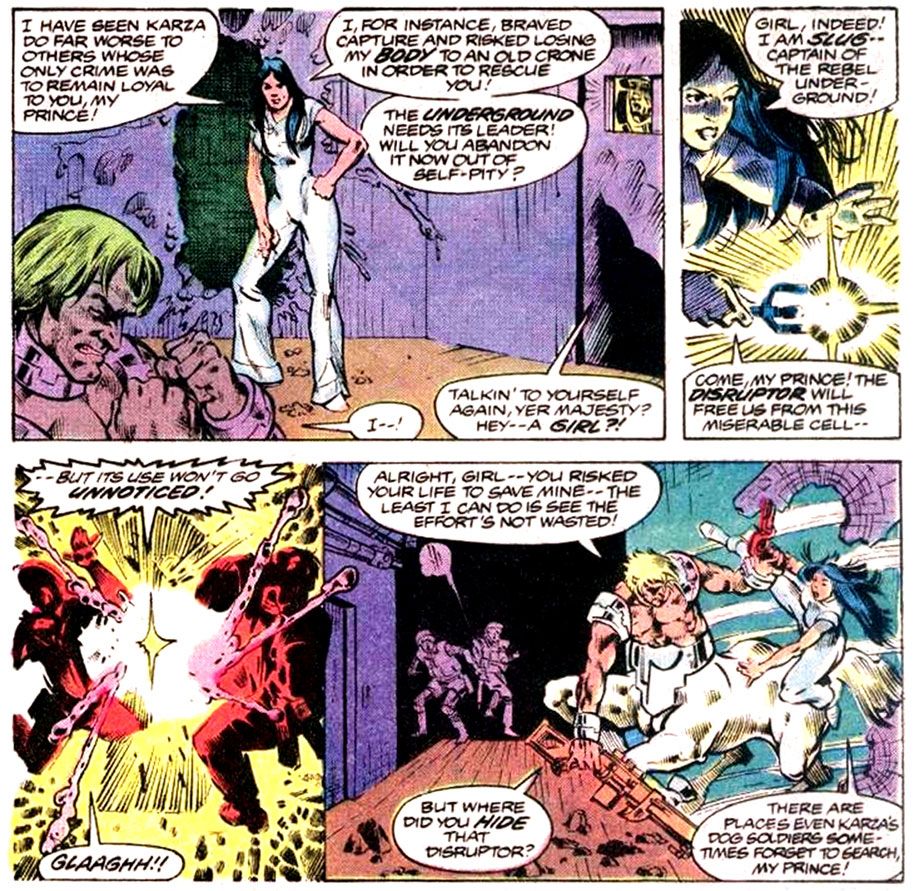

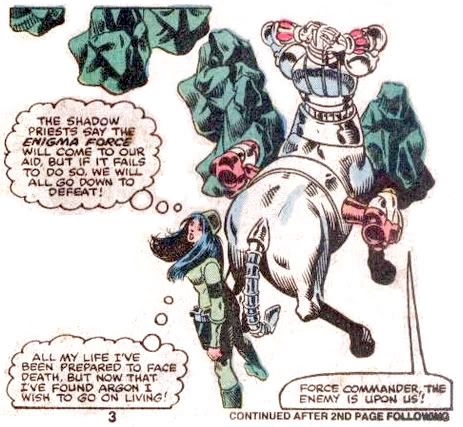

Slug. Not her real name, yet not exactly a nickname. A nom de guerre, if you will, but more than that. Slug debuts in the story "A Hunting We Will Go" from the second issue I bought fresh off the spinner rack, Micronauts #4 (April 1979). The book features splendid art by Michael Golden and Josef Rubinstein and I can't figure out why this team wasn't used on Marvel's Star Wars title. Right from the splash they delight readers with high-tech vehicles, a chaotic firefight and lots of everyday type slobs caught in the middle as minor villain Major D'Ark commands an assault on "Sector 7" of Homeworld, the comic's main planet (other than earth, of course). Dodging lasersonics, laser bolts or beams or blaster shots or whatever, Slug jumps into a hole in the wall and changes clothes with a dead man for no apparent reason. After all, it's not as if the rebels wear uniforms or that she wouldn't tip off the bad guys with her defiant eye-squint among a bunch of stunned, gape-mouthed goobers. Somehow this clothes-swap makes someone known only by name and reputation completely anonymous. From there she goes to the worst possible place on Homeworld. By design.

Where did this woman come from? In her brief, violent life, we don't learn a whole lot about her or her motivations, and precious little biography. Mantlo wouldn’t even reveal the story behind her humble handle for another three years, in Micronauts #48 (December 1982). This is when we learn doomed, defiant Slug was born to a prisoner of Baron Karza, the science-mad dictator of the Microverse. She became Slug via one of Karza’s offhand insults as soldiers drag her mother away. With whatever name her parents gave her left unsaid, it's Slug she remains for the rest of her life. The only question is, who told her she was a Slug?

Where did this woman come from? In her brief, violent life, we don't learn a whole lot about her or her motivations, and precious little biography. Mantlo wouldn’t even reveal the story behind her humble handle for another three years, in Micronauts #48 (December 1982). This is when we learn doomed, defiant Slug was born to a prisoner of Baron Karza, the science-mad dictator of the Microverse. She became Slug via one of Karza’s offhand insults as soldiers drag her mother away. With whatever name her parents gave her left unsaid, it's Slug she remains for the rest of her life. The only question is, who told her she was a Slug?Because she's a secondary character rather than main cast, Mantlo never fills us in on what Slug does between birth and rebellion. This means we're free to imagine the hardscrabble life Slug must have lived from that day. Homeworld hosts a hierarchical society with Karza on top, followed by the wealthy elite who support his tyranny. At the bottom, the poor, mostly used by Karza as a recruiting pool for his Dog Soldier armies or for experiments in his Body Banks, the genetic madhouse where Karza dissects and maims at will. It's obviously a dehumanizing system. An orphan among its lowest class, Slug probably learned to steal and hide at first, and later to fight.

Emphasis on the fighting, because when she first appears Slug is already the semi-legendary leader of the anti-Karza rebellion, no doubt using her street smarts and toughness to plan and survive running street battles with the Dog Soldiers—until she allows herself to be captured. Locked away inside the Body Banks herself, Slug faces the potential horror of having her body taken from her and given to a loyalist. But before that can happen, she uses an energy weapon (I don’t even care to speculate where she hid it, because in on scene she’s forced to disrobe completely in front of Karza’s men) and breaks into the cell of Prince Argon, who’s already suffered the indignity of having his upper body surgically grafted to his horse’s lower body. You know it could’ve been worse: if Karza had more of a sense of humor, he might have done it the other way around. I would have. Look into your heart and you may find you would have, too. Since he didn't, we're free to imagine somewhere in the unseen sections of the Body Banks, there's a horse head running around on human legs.

Emphasis on the fighting, because when she first appears Slug is already the semi-legendary leader of the anti-Karza rebellion, no doubt using her street smarts and toughness to plan and survive running street battles with the Dog Soldiers—until she allows herself to be captured. Locked away inside the Body Banks herself, Slug faces the potential horror of having her body taken from her and given to a loyalist. But before that can happen, she uses an energy weapon (I don’t even care to speculate where she hid it, because in on scene she’s forced to disrobe completely in front of Karza’s men) and breaks into the cell of Prince Argon, who’s already suffered the indignity of having his upper body surgically grafted to his horse’s lower body. You know it could’ve been worse: if Karza had more of a sense of humor, he might have done it the other way around. I would have. Look into your heart and you may find you would have, too. Since he didn't, we're free to imagine somewhere in the unseen sections of the Body Banks, there's a horse head running around on human legs.Flights of horse-ass based fantasy aside, Slug quickly convinces the despairing Argon to fight for his life and they blast their way out of the Body Banks. With Slug riding on Argon’s back. Which is pretty sensible, when you think about it. After all, it is a horse's body which means it has horse's legs. Strong and fast enough for both Slug and Argon to make good their escape.

After that, Slug doesn’t contribute a whole lot to the fight against Karza, at least not on-panel. But when Mantlo and Golden do depict Slug in action, it’s to gun down some rich jerks who won’t join the rebellion. That’s pretty hardcore. Che Girlvera.

This happens in Micronauts #7 (July 1979). Yes, Argon, what a queen Slug would make. The queen of summary executions.

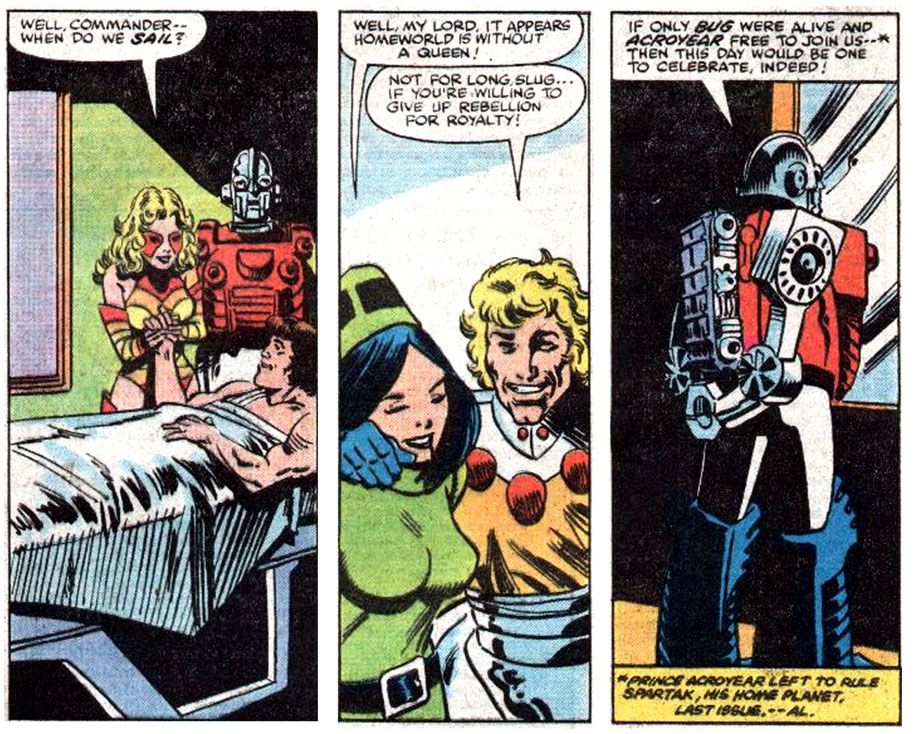

Fighting for freedom side-by-side (the freedom to be ruled by a king instead of a baron), the two fall madly in love. Under Slug's influence, Argon dons King Dallan’s holy armor, which looks like the negative version of Karza’s unholy armor. Despite being something of a dumbass as it turns out, Argon takes charge of the rebellion, no doubt coached at every turn by the more-capable Slug. At least I hope that's the subtext Mantlo intends as he relegates Slug to a more supporting role in the conflict. But despite lacking Slug's brains, Argon does have four hooves and a couple of rockets on his back, and so proves himself every bit as gutsy as his girlfriend.

Fighting for freedom side-by-side (the freedom to be ruled by a king instead of a baron), the two fall madly in love. Under Slug's influence, Argon dons King Dallan’s holy armor, which looks like the negative version of Karza’s unholy armor. Despite being something of a dumbass as it turns out, Argon takes charge of the rebellion, no doubt coached at every turn by the more-capable Slug. At least I hope that's the subtext Mantlo intends as he relegates Slug to a more supporting role in the conflict. But despite lacking Slug's brains, Argon does have four hooves and a couple of rockets on his back, and so proves himself every bit as gutsy as his girlfriend.By Micronauts #12 (December 1979), with the war against Karza apparently finished, Slug prepares to hang up her guns and start exploring the softer side of life. The very same young woman who once blew the upper class away with a laser-blaster coquettishly melts into the arms of the heir apparent. You can’t help but think Slug feels a little pang of guilt when Argon asks her in #13 (January 1980) if she’s ready to trade rebellion for royalty. Or not. Her politics are more than a little odd when you consider her rebellion wasn't a democratic one by any means. It was more of a pro-monarchist insurrection. She fought to replace an autocratic regime with an aristocratic one, not to give the people a voice in their government, unless revolution counts as a voice. Now that I think it over, I'm sure it does. I prefer elections to violence, however, but with a monster like Karza in charge, Slug and her fellow rebels didn't have that choice. Whatever her former beliefs, Slug seems happy to hint at a new role for herself. She's to marry into royalty as her reward.

Life afterwards doesn't go as smoothly as Slug might have hoped, despite being drawn for a few issues by Howard Chaykin, with inks by series editor Al Milgrom. Chaykin was penciller on Marvel's Star Wars movie adaptation, so he might have seemed a natural fit for Micronauts, just as Golden would have been for that other property. Unfortunately, Milgrom's inks are far from sympathetic and give the book a rushed look. Which it may very well have been-- Micronauts features a lot of complex machinery and a massive cast so it must have been a chore for art teams to meet deadlines. And even when matched with ideal material, Chaykin never had much luck with inkers at Marvel. He fared much better doing his own finishes in his American Flagg series at First Comics.

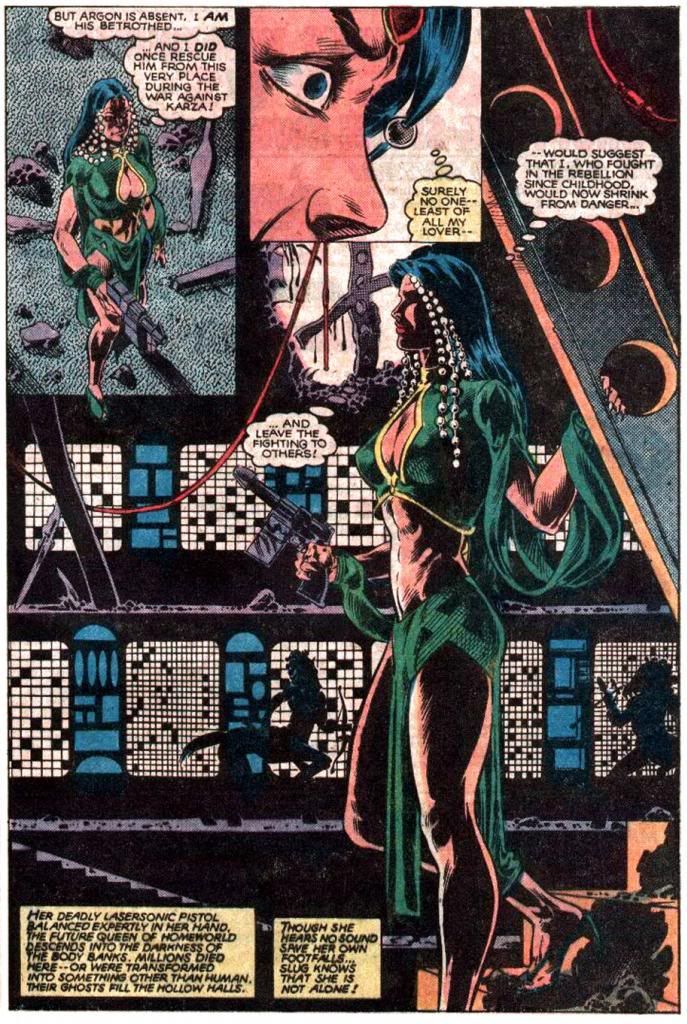

Possibly as disappointed by the art as I was at the time, Slug slinks away until Micronauts #22 (October 1980), and when she reappears, she's still a fiesty one. And more than a little strident, a trait she hadn't evidenced before despite having been a fine leader. Guess success does that to a person. New artist Pat Broderick with his Michael Golden-esque style has Slug ditch her tomboyish green fez and functional pantsuit look for space lingerie and strands of pearls in her hair.

This choice seems a little off given Slug's rough-and-tumble origins, but as a character look it has precedents. Maybe it's because of Dejah Thoris, Edgar Rice Burroughs's original space queen. From what I understand, Martians of her tribe generally run around naked but for some jewelry (they think clothes are weird, which, from a quick Google search for new Dejah Thoris comics, proves convenient for today's comic book artists whose only exposure to female anatomy seems to have come from porn magazines). Alex Raymond contributed Princess Aura and Queen Azura. They're pretty modest by Barsoomian standards but like leisure Slug, they favor mid-drift exposure in jeweled bras and diaphanous skirts. No doubt directly inspired by those two creations, Al Williamson and Wally Wood favored this look for their female characters in various EC titles. Broderick's Slug is very much drawn in this tradition.

While we're on the topic of costumes, I'm going to challenge artists of our next generation of space princesses and guerilla-girls-turned-space-princesses to draw some inspiration from the Renaissance, or even the Baroque or Rococo periods. Not because I'm against skin (check out some Francois Boucher paintings), but because this kind of finery has regality and offers ample opportunities for sumptuous drawings of lace and folds and printed patterns, plus differing fabric textures. Your Dejahs and Auras are fine and dandy, but my image of the ideal space princess is Virginia Madsen as Irulan in David Lynch's 1984 adaptation of Dune. We just don't see this kind of thing often enough, but we have plenty barbarian-queens-in-silk-or-metal-bikinis imagery.

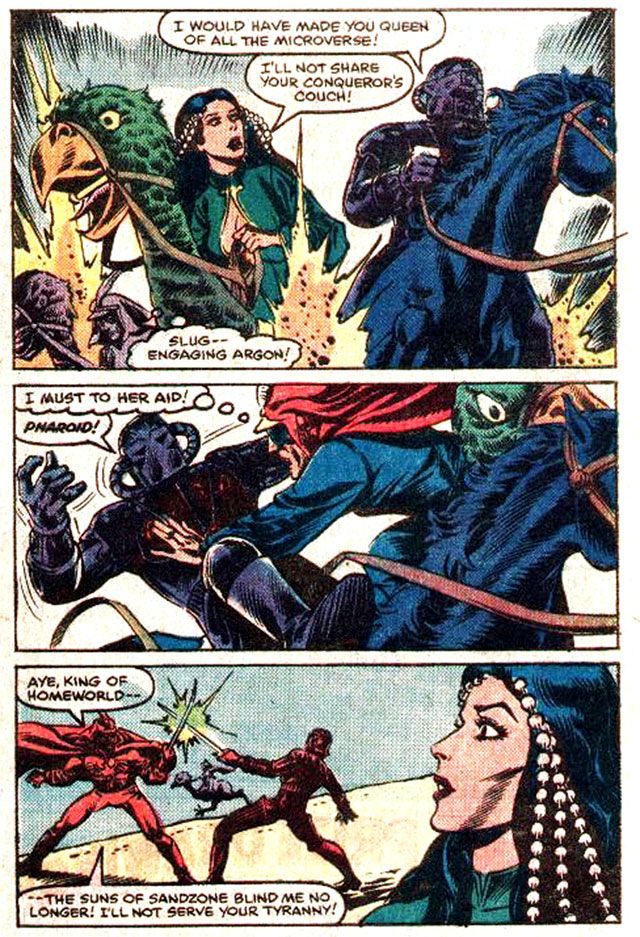

And whatever Slug's new fashion sense, it doesn't prevent her from finding a world of trouble. Argon abruptly kidnaps her to Aegypta, a desert-like zone of Homeworld-- more Flash Gordon influence; Homeworld is made up of different zones each with its own distinct ecosystem, much like Mongo-- where men are men and women are women and everyone rides green ostriches. There she's rescued by Pharoid, the leader of the ostrich-riders. Like Argon before him, Pharoid falls madly in love with Slug but unlike his romantic rival, he spends the rest of his days trying to prove worthy of her.

But why does Slug's fiance drag her against her will into the desert in the first place? Well, it has to do with the nature of mainstream comics where a good villain can never stay dead and a popular story has to repeat itself. Even with an entire micro-galaxy possibly full of all kinds of heretofore never-seen-in-comics stories to explore, the Micronauts still end up fighting massive space wars against Karza, twice after he's possessed or otherwise transformed poor, stupid Argon.

The first plot redux renders Argon the mindless slave under the influence of Karza's mind control. After Mantlo thoroughly sets the stage for it, Argon jumps into a live volcano and comes out transformed into the arch-villain. Once again it's our heroes against Karza, and Slug does her part largely off-panel. The main fighting takes place in a pseudo-Disneyland between the forces of Karza and those of SHIELD, led by good ol' Nick Fury.

Actually, after her kidnapping, Slug's major contribution to the war is to stand by Prince Argon at the mass funerals that conclude the storyline. Given the circumstances, they make an appropriately downbeat pair, but at least Argon has his human legs back.

The next time Karza rears his ugly mind, Slug watches as her beloved dimwitted Argon lowly goes insane, first bringing back the Dog Soldiers as his personal guard in Micronauts #34 (October 1981) and then declaring his rule absolute. To have your Argon transform into Baron Karza once is unfortunate; twice smacks of carelessness. As for Slug, she finally starts to rethink her commitment to a man who can't decide who he is today-- nice king in white or totally different guy in black. When Argon dons Karza's armor and declares the Micronauts outlaws while ranting and raving like a loony, Slug has had enough. Now riding her very own green desert ostrich, she attacks her fiance, only to have Pharoid jump in and reduce her to an observer. At this point it's been quite a while since Slug actually did much of anything, but this desultory attempt at reclaiming her "action girl" is her next-to-last attempt at reclaiming agency. And she does so while wearing her pearls and bra look again. Does she own only the one outfit?

You probably wonder yourself what kept Slug attached to the increasingly pathetic Argon for so long. Perhaps it's the chance to have herself drawn by the legendary Gil Kane, who takes up the pencils with Micronauts #40 (April 1982), inked by Danny Bulanadi, who transforms him into a pseudo-Broderick.

With his slick feathered modeling and heavy black-spotting, the stalwart Bulanadi provided visual continuity on a book that must have been hell on pencillers to judge by the turnover on art. In those days, pencillers usually didn't do the tight rendering they do now and it was up to inkers to finish the art and make things look more or less the same from issue to issue. Bulanadi was a master at this-- Val Mayerik breakdowns, a short run of Keith Pollard pencils, even a single issue by as unique a stylist as Steve Ditko look almost identical apart from differing approaches to page layouts and character dynamics. Along came Kane, who was born for this book despite having a more linear approach and a surer hand with the storytelling than either Golden or Broderick. Bulanadi knocks himself out on the finishes, but we lose a lot that's essentially Gil Kane.

Maybe longtime readers would have balked at such a radical departure on the interiors, but at least Kane was able to ink his own covers. Eventually, the massive workload of Micronauts ground down Kane, who switched to supplying only breakdowns, with Bulanadi maintaining the book's look. I don't know about you, but those pure Kane covers make my mouth water for something more characteristic of his work.

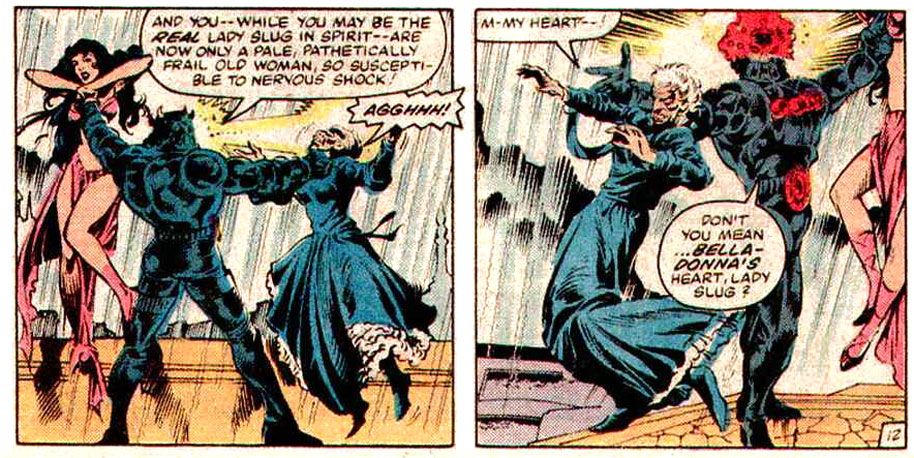

In the end, Argon has Slug's soul switched into the body of Lady Belladonna, a dessicated old poop and Karza loyalist. The plan is for Argon to wed Belladonna in Slug's body and not tell the people of Homeworld. That way they'll see that no matter how much of a tyrant he becomes, at least one of the great anti-tyrants of our time loves him enough to marry him. That's suppose to shut up any protests. Here at the bitter end of her career as rebel and royal, Slug gets a few panels hobbling around with a gun. Then the body-switched women team up to infiltrate the Body Banks in a desperate bid to fix themselves, but it's too little, too late for Slug. She's been reduced to complete ineffectuality.

In Micronauts #49 (January 1983), as pencilled this time by Jackson "Butch" Guice, Argon literally rips himself in half and out steps a fully-formed Karza, which should have surprised no one. Well, the tearing himself in half might have been a shocker, but the re-emergence of Karza wouldn't have been for anyone with a brain. In the rain, while everyone engages in a massive comic book fist fight, Belladonna's aged body simply gives out from the strain with Slug still inside it and then Karza throws her younger form against a wall, breaking its neck and killing Belladonna as well. That happens in Micronauts #50 (February 1983). The series went on for another two years, but among the various deaths and resurrections, there's nothing remaining for a character introduced with a bang and disposed of with a whimper. Poor Slug.

The Microverse is kind of a dark place, isn't it? Makes Macbeth seem sort of cheerful by comparison. Characters die all the time, heroic Commander Rann suffers all kinds of torments and loses his hand, Karza commits genocide on a planetwide scale. So maybe it's thematically fitting Slug's infancy was so harsh, her life full of conflict and tragedy, her attempts at fighting for life and freedom abortive, her death abrupt and anti-climactic.

Friday, July 26, 2013

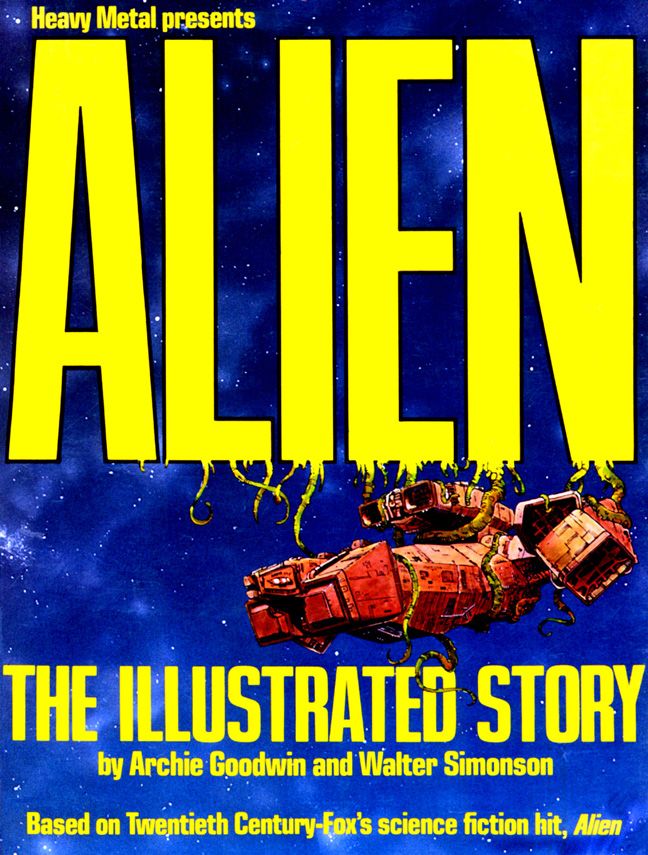

Let's take a moment to appreciate Alien: the Illustrated Story

Years before Dark Horse introduced the infamous xenomorphs into comics, Heavy Metal had Archie Goodwin and Walter Simonson team up for Alien: The Illustrated Story, an adaptation of the first Alien movie. Kind of a strange item. While its publishers aimed Heavy Metal magazine at adults, I'm not sure how much of an audience existed at the time for what amounted to a full-color graphic novel based on an R-rated film. People read Heavy Metal, people went to see Alien. Were these the same people? Or, if not, could they be brought together in the bookstore for a book self-consciously eschewing the comic book label in favor of this "illustrated story" invention? Someone thought so, hence this book.

Somehow its existence escaped me the first go-around-- and I've been a huge fan of Ridley Scott's sci-fi horror flick since I was approximately ten years old. I was a fan of it even before I was old enough actually to see it, mainly because one of my brothers saw it and liked it enough to buy a book about its production, which he passed on to me. And which thoroughly grossed me out and fascinated me at the same time. Even stranger, there were Alien action figures in the toy store at the mall. The point is, much like the unfortunate John Hurt character in the movie, I was exposed to the spore and it grew inside me. It wasn't until a couple of years later, on an appropriately stormy night while I was home alone that I was finally able to watch the film on HBO. It didn't scare me (and I'm easy to scare), but I enjoyed the horror elements and the funky, shabby-looking spaceship.

Years passed and I found out about Alien: The Illustrated Story, probably from one of the TwoMorrows magazines. Since I'm also a fan of both Goodwin and Simonson (but not Heavy Metal magazine itself or the Dark Horse series for some reason) I went to Ebay and there it was. Even though it was out of print at the time, I bought a nice, clean copy for a fairly cheap price. It's probably not mint, but then I bought it to read not to file away in some climate-controlled vault.

But what a book! It exceeded my expectations in every way.

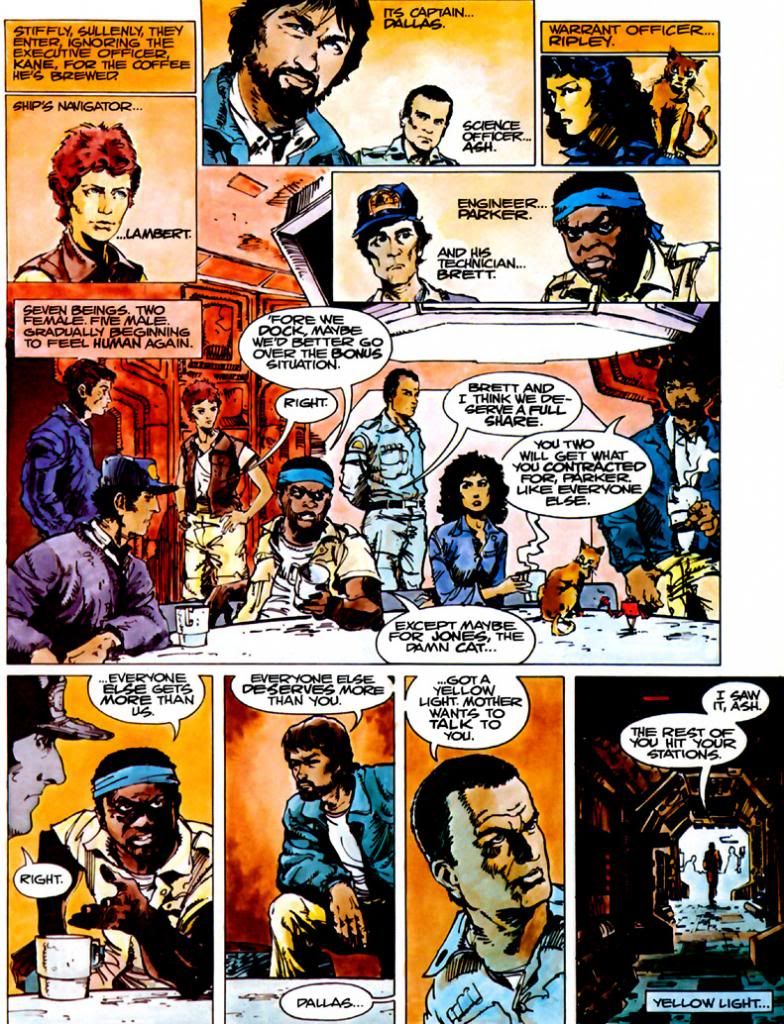

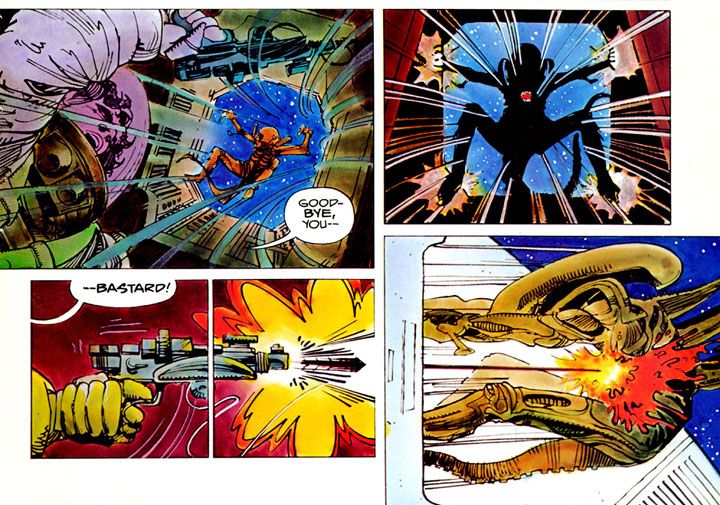

Goodwin confines himself largely to dialogue, with just a few tersely-worded captions here and there, most prominently on the first and last pages bookending the story. He provides just enough information to get us started, then smartly leaves Simonson to carry the narrative load. Simonson does an absolutely smashing job. It's obvious from the way he stages certain sequences and from the accurate costuming he had access to a lot of studio-provided material, but Simonson doesn't let himself get too involved with photo reference. If he had, it would have resulted in some dull storytelling. His likenesses are more along the lines of caricatures rather than portraits, which is another canny decision from a guy who flat-out knows how to play to his own strengths. Simonson has long had a loose approach to anatomy matched with a kind of abstract, angular take on shadows and wrinkles. More in the Noel Sickles-Milt Caniff school of impressionist-style cartooning rather than flashy photorealism. If you want photorealism, you might as well just use stills and do a fumetti book. You get Simonson for an illustrative approach.

Because it follows the film very closely, there's a lot of talk in this book, with characters discussing the "bonus situation" and what to do about the alien. The movie has some memorable gore-- the chest-bursting scene, for example-- but for the most part it's a masterpiece of claustrophobic tension and production design. There's not a lot of comic book-style action. Rather than allow this to hamper his storytelling, Simonson finds ways to mimic Giger's "biomechanical" design sense with alienesque panel borders and then the occasional torrents of blood. It's some of his finest work, a little bit Moebius (a frequent Heavy Metal contributor who spent a short time working on the Alien film) and a touch Cam Kennedy, who was doing some fine work for Fleetway around this time and later did some of the most visually distinctive Dark Horse Star Wars comics.

Somehow its existence escaped me the first go-around-- and I've been a huge fan of Ridley Scott's sci-fi horror flick since I was approximately ten years old. I was a fan of it even before I was old enough actually to see it, mainly because one of my brothers saw it and liked it enough to buy a book about its production, which he passed on to me. And which thoroughly grossed me out and fascinated me at the same time. Even stranger, there were Alien action figures in the toy store at the mall. The point is, much like the unfortunate John Hurt character in the movie, I was exposed to the spore and it grew inside me. It wasn't until a couple of years later, on an appropriately stormy night while I was home alone that I was finally able to watch the film on HBO. It didn't scare me (and I'm easy to scare), but I enjoyed the horror elements and the funky, shabby-looking spaceship.

Years passed and I found out about Alien: The Illustrated Story, probably from one of the TwoMorrows magazines. Since I'm also a fan of both Goodwin and Simonson (but not Heavy Metal magazine itself or the Dark Horse series for some reason) I went to Ebay and there it was. Even though it was out of print at the time, I bought a nice, clean copy for a fairly cheap price. It's probably not mint, but then I bought it to read not to file away in some climate-controlled vault.

But what a book! It exceeded my expectations in every way.

Goodwin confines himself largely to dialogue, with just a few tersely-worded captions here and there, most prominently on the first and last pages bookending the story. He provides just enough information to get us started, then smartly leaves Simonson to carry the narrative load. Simonson does an absolutely smashing job. It's obvious from the way he stages certain sequences and from the accurate costuming he had access to a lot of studio-provided material, but Simonson doesn't let himself get too involved with photo reference. If he had, it would have resulted in some dull storytelling. His likenesses are more along the lines of caricatures rather than portraits, which is another canny decision from a guy who flat-out knows how to play to his own strengths. Simonson has long had a loose approach to anatomy matched with a kind of abstract, angular take on shadows and wrinkles. More in the Noel Sickles-Milt Caniff school of impressionist-style cartooning rather than flashy photorealism. If you want photorealism, you might as well just use stills and do a fumetti book. You get Simonson for an illustrative approach.

Because it follows the film very closely, there's a lot of talk in this book, with characters discussing the "bonus situation" and what to do about the alien. The movie has some memorable gore-- the chest-bursting scene, for example-- but for the most part it's a masterpiece of claustrophobic tension and production design. There's not a lot of comic book-style action. Rather than allow this to hamper his storytelling, Simonson finds ways to mimic Giger's "biomechanical" design sense with alienesque panel borders and then the occasional torrents of blood. It's some of his finest work, a little bit Moebius (a frequent Heavy Metal contributor who spent a short time working on the Alien film) and a touch Cam Kennedy, who was doing some fine work for Fleetway around this time and later did some of the most visually distinctive Dark Horse Star Wars comics.

Another amazing aspect of this book is the lettering by John Workman. This is the kind of stuff where the lettering is fully integrated into the artwork itself rather than just covering up parts of it. And finally, the coloring. I haven't seen the "re-mastered" version from Titan Books, so I don't know if they preserved the watercolor appearance, but back in the day, this is how the high-end graphic novels all looked (although few others really looked as good as this). The coloring style allows for extremely subtle gradients and blends so it's richer and more sumptuous than computer coloring.

Wednesday, July 17, 2013

Mad #1 for the very acceptable price of zero dollars and zero cents!

I checked out Comixology last night and found a run of the early full-color comic book days of venerable humor mag Mad. The premiere issue (October-November 1952) is free and the others are $1.99, which seems to be Comixology's (or DC's) basic price point for classic reprints. Of course I snagged the free issue and I plan to buy the others as soon as I'm able. Lots of expenditures happening right now that take precedence over my comic book addiction.

Mad magazine. You may have heard of it. Does anyone still read Mad? Is Mad still relevant or even irrelevant these days? The last time I discussed Mad magazine with anyone it was Jack Davis himself way back in 1996 and his take was he didn't care that much for whatever it was Mad was doing that year. But because he's Jack Davis, one of the classiest gentlemen ever to work in comics, he didn't belabor the point and we got back to discussing working methods and materials.

Strangely enough, this comes a day after I spent an after-school teacher's meeting drawing Alfred E. Neuman over and over in various styles on my hand outs. And also other characters saying, "What? Me worry?" And less than a week after learning right here on this blog that Comic Book Creator magazine has a look at Harvey Kurtzman in the works (something I'm very much looking forward to, since I know very little about Kurtzman or his career despite his having influenced my sensibilities and those of millions of other kids who grew up with Mad).

NOTE: And for those of you who enjoy my idiot take on vintage comics, I have a massive post coming up about Slug. Remember Slug? She was the rebel leader from Marvel's Micronauts comic. There's not enough information about Slug online so I'm doing my part to increase the load.

Mad magazine. You may have heard of it. Does anyone still read Mad? Is Mad still relevant or even irrelevant these days? The last time I discussed Mad magazine with anyone it was Jack Davis himself way back in 1996 and his take was he didn't care that much for whatever it was Mad was doing that year. But because he's Jack Davis, one of the classiest gentlemen ever to work in comics, he didn't belabor the point and we got back to discussing working methods and materials.

Strangely enough, this comes a day after I spent an after-school teacher's meeting drawing Alfred E. Neuman over and over in various styles on my hand outs. And also other characters saying, "What? Me worry?" And less than a week after learning right here on this blog that Comic Book Creator magazine has a look at Harvey Kurtzman in the works (something I'm very much looking forward to, since I know very little about Kurtzman or his career despite his having influenced my sensibilities and those of millions of other kids who grew up with Mad).

NOTE: And for those of you who enjoy my idiot take on vintage comics, I have a massive post coming up about Slug. Remember Slug? She was the rebel leader from Marvel's Micronauts comic. There's not enough information about Slug online so I'm doing my part to increase the load.

Labels:

Comic Book Creator,

Comixology,

free comics,

Harvey Kurtzman,

Jack Davis,

Mad,

Micronauts,

Slug

Wednesday, July 10, 2013

TwoMorrows, TwoMorrows, I love ya TwoMorrows...

Last weekend I started thinking about that old TwoMorrows magazine Comic Book Artist again. Why? Heck, you're reading this blog, aren't you? Anyway, I did a quick Internet search and discovered TwoMorrows sells PDF versions of all their titles-- things like CBA, Back Issue, my beloved The Jack Kirby Collector, Draw, Rough Stuff and Alter-Ego.

That's right-- PDF versions, super cheap. When a flimsy nothing of a new comic costs as much as $3.99 and takes you all of five minutes to read a fun-packed issue of any TwoMorrows mag for $2.95 or 3.95 isn't just a relative bargain. For a hardcore comic fan, it's a bargain by any measure. Plus, unlike digital comics, you buy a magazine, download it to your computer and enjoy it for as long as you and your hard drive do live. None of this "you're buying just a license to read our comics when you're online and on our site" jazz some of the other outlets offer.

I understand why those sites feel obligated to do this and I absolutely agree to abide by their rules when they offer something I want (like Fantastic Four #1 for $1.99), but obviously the TwoMorrows model is the one I love most. It's risky and they attach a page practically begging you not to pirate their publications, but apparently TwoMorrows trusts me. It's this level of trust they offer along with their fun mags that makes me want to earn it. It gives me that ol' "we're in this together, fellow fans" same-wavelength feeling I used to get from comic book letters pages. If it's a naive business model, I'll take honest naivete and a sense of wonder over sneering cynicism any day and I'll support TwoMorrows because their brand of thinking is what we need more of in this world of ours.

How did TwoMorrows hook me? Many years ago when I lived in Athens, Georgia, and worked at the local newspaper as a graphic artist (kinda), I had my first taste of disposable income. And what I chose to buy with said income (besides lots and lots of booze) one blisteringly hot summer day was The Jack Kirby Collector. I probably bought it because of the cover. I was going through a very Kirby-inspired period in my comic book-related artwork and I was always on the lookout for cool Kirby images to copy. The magazine interior turned out to be just as cool, with lots of reproductions of Kirby pencils and appreciations of the man and his work by dedicated Kirby enthusiasts. Fanatics, really.

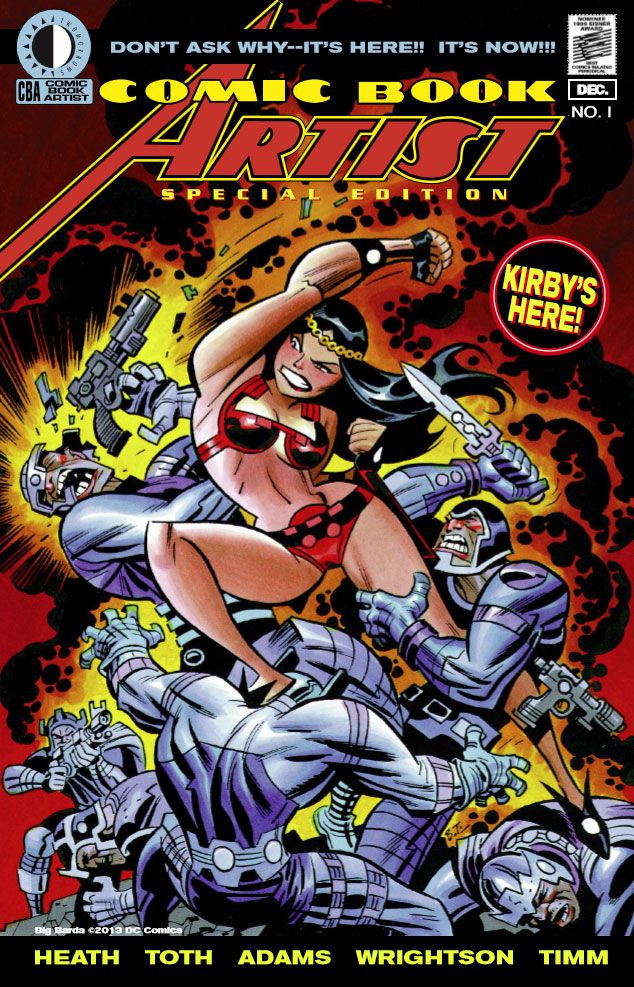

As much as I enjoyed TJKC, I felt compelled to subscribe to their next major offering, Comic Book Artist. And subscribing to magazines wasn't something I did very often. In fact, the last time I subscribed to a comic or comic-related publication was The Uncanny X-Men back when I was a teen. But I had a hunger for old school comic book art and CBA provided a feast. Another reason I subscribed was to get a copy of the Comic Book Artist Special Edition. That was the only way to get it at the time.

As you can see from the picture I chose for this entry (I bought it digitally, of course), CBASE has a snazzy Bruce Timm cover of Big Barda opening up a can of whup-ass on some Apokalips soldiers, my favorite non-Jack Kirby rendering of one of my favorite Jack Kirby characters. The cover alone is worth both the subscription and the digital re-purchasing price, but look at the artist lineup along the bottom-- Russ Heath, Alex Toth, Neal Adams, Bernie Wrightson and Timm. Inside, you'll find interviews with and info on all those guys, as well as a lot of Kirby love, a consistent aspect of all of TwoMorrows' products except maybe their Lego-centered magazine and possibly even that as well.

And after I got into CBA along came Draw. While artist bios and the histories of various companies and titles are all very interesting to read, I've always been even more into process. Who said what is fine, but what I really want to know is who drew how. As an artist, I want to know how the pros lay out their pages, how they create depth and contrast, what the significance of various storytelling choices are, how to construct figures, to produce finished pencils and inks. Yeah, I bought Draw.

When I moved to Japan, I couldn't get Draw, CBA or TJKC anymore, but their influence lingered as I used my now even-larger disposable income to buy archive reprints of Kirby' work, Creepy, Eerie, Blazing Combat and Nexus. Kinokuniya in Shinjuku stocked TwoMorrows' Modern Masters book series, so I was able to at least pick up some of those. Now, however, I'm reunited with the magazines and it feels right.

This week I also bought the inaugural issue of Comic Book Creator, which features Kirby most prominently, but also a great interview with Derf Backderf, writer/artist of the graphic novel My Friend Dahmer. There's an article on Frank Springer, a chat with Alex Ross. The usual TwoMorrows stuff. Marking the return of former CBA editor Jon B. Cooke to the TwoMorrows family, Comic Book Creator has another thing going for it-- advocacy.

On that note, we're going to turn to something a little more serious.

In this time of comic book movies opening massively worldwide the people and the families of people who actually invented these lucrative properties aren't receiving a fair share. And when they resort to legal measures to try and reclaim things they should have owned all along (in world where publishers back in the day didn't practice the fine art of ripping off artists and writers-- the bosses at Timely Comics regularly shorted Joe Simon and Jack Kirby on royalties contractually due to them from their creation of the wildly successful Captain America), fans of the very works they created accuse them of greed.

Greed. One side is praised for maximizing profits, the other is derided for asking for a share. I've read plenty of comments online knocking the Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster families as greedy for suing Time-Warner for the Superman rights (or Warner Bros., as the case may be) while defending massive communications companies that reap record-making profits with little or no regard for the hard-working individuals whose talents and efforts made this possible in the first place.

Under the first article I linked in the above paragraph, you'll find one of those comments: Siegel and Shuster sold their rights, so their heirs deserve nothing, and note their interest in the money came only after "DC's hard work."

Somehow it's the company itself that worked hard, not the various human beings who did its labor over the decades. And apparently, Siegel and Shuster produced Superman while lounging around in pajamas being hand-fed peeled grapes. No toil there. Coming up with Superman was nothing compared to the trials and difficulties of being a major corporation. And certainly Siegel and Shuster "took the profits happily" in that deal-- read some history and learn how much profit they made compared to the corporate income they generated, how happily they were treated while producing Superman stories for National and how happily ever after they lived when the company was finished with them. And this isn't something that just recently popped up. Siegel and Shuster tried to reclaim the Superman rights as early as 1947. Various people around both creators have fought this battle or similar ones for years.

In this Bizarro World logic, gigantic media conglomerates provide everything of value, and the creative minds who worked for them-- who created all their media properties-- and their surviving families are parasites. To their accusers, if someone signed one of the shitty contracts comic book publishers offered in those days-- the only avenue to this kind of labor available to you at the time-- then screw you, jack.

And Jack. In Jack Kirby's case, certain parties deliberately jerked him around with various attempts to deny him any kind of legal claim to rights ownership. It's not that Kirby didn't make mistakes or poor decisions. Cooke in his pro-Kirby article is very forthcoming about these as well. But the man wasn't a lawyer or an agent. He was a writer and artist. He was a husband and father, a provider who had to make the best living he could for his family, using his talents to their utmost. He did this without a pension, without a retirement plan and with the knowledge that no matter how many Silver Surfers he came up with, he was never going to share the wealth generated. Or even receive just credit for creating them, which was another huge concern of his. And that the moment he could no longer come up with those ideas or push that pencil, then he was through with no means of support. I'm sure Kirby was very aware of what happened to Siegel and Shuster, Bob Finger, Reed Crandall and Wally Wood, just to name a very few.

But given the importance of Kirby to the industry, his treatment was proportionally worse. The companies he worked for knew too well just how much Kirby's ideas were propping up their entire comic lines and how much of a hold he could have had over them. So the man they labeled "the King" on the credits pages weathered insults and interference from staffers, attempts to get him to sign onerous contracts, the refusal to return his artwork until he signed a four-page agreement waiving any future rights and ownership claims (Marvel lawyers expected Kirby and only Kirby to sign the four-page version; everyone else got a one-page form)-- and even when they did after a protracted struggle, thousands of pages went missing and unaccounted for.

No wonder he split the comics scene for TV animation. And even there, he couldn't shake loose from the shabby treatment. Kirby did storyboards for the 1978 Fantastic Four cartoon, and a few years later someone had the bright idea to have them inked and published as a new Jack Kirby story in Fantastic Four #236-- minus any kind of permission from or payment to Kirby. Yes, he was paid to do the artwork for its first use, but double-dipping on the man and fobbing it off as some kind of tribute like this is unforgivable. Adding to the weirdness, there's also the matter of Kirby or his lawyers asking his image be removed from John Byrne's cover because he and Marvel were at legal odds yet again at the time.

It's hard to view any of this as unfortunate but accidental by-products of best business practices.

Without Kirby, there would have been no Marvel Age of comics, no Spider-Man or X-Men film franchises, no Disney deal, no Joss Whedonverse Avengers movie. Factor in all the cartoons, reprints, other comic book series, toys and the like that have all used elements of Kirby's concepts, which have generated billions of dollars in revenue. That Kirby did this work during a time of unfair labor practices-- no matter how legal they may have been at the time-- is no reason to deny his family their deserved percentage of what Kirby made possible.

That's all there is to it.

Oh, and I also have a fond spot for TwoMorrows because they printed one of my love letters in CBA.

Monday, July 8, 2013

Hulk Cassidy and the Sundance Thing: The Early Days

Okay, actually it was just Butch and Sundance: The Early Days without their surnames, but that didn't have enough of that pop culture fusion stupidity I enjoy so much (to the detriment of all my personal relationships). And those two guys actually got along much better than the Hulk and the Thing. The Hulk and the Thing are Marvel's two heavy hitters and their dust ups from the first few years of Fantastic Four are pure comic book fun.

First, you have the Thing. A mouthy orange rock-man, the muscle and the ever-lovin' heart of the Fantastic Four. The Thing was essentially nice. Who the heck could hate the Thing? Then, you have the Hulk. In the 1960s, at least for a time, the Hulk had a command of language beyond simple statements in favor of smashing, or admonishments to puny humans to leave him alone. He was an anti-hero hearkening back to Marvel's early years when they put out comics where Namor would show up pissed off for whatever reason and start tearing up the place. Namor was the kind of dangerous character you rooted for only because he was fighting Nazis (only other Nazis root for Nazis), mad scientists or because he was like your own repressed child-id striking back at adult authority figures-- otherwise, Namor was angry specifically at you, the reader, for existing on land. It's a similar story with the Hulk and Space Age-era Communists and outright villains.

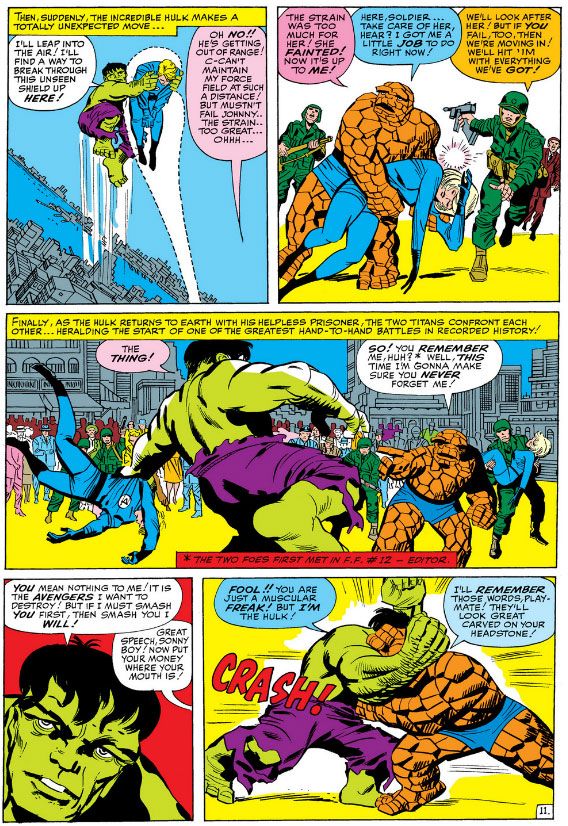

With two opposing forces like these in a single comic book universe, it was only a matter of time before they clashed. And clash they did in Fantastic Four #12 (March 1963) by Stan Lee, Jack Kirby and inks by Dick Ayers, from those fabled days when Kirby hadn't yet settled on the correct number of fingers and toes for the Hulk. In this issue, the Jade Giant flaunts three of each, plus opposable thumbs for a grand total of fourteen digits. Strangely enough, the same number sported by the Thing. That's okay, because there's at least one instance of Mr. Fantastic showing six on one hand in a later issue.

With two opposing forces like these in a single comic book universe, it was only a matter of time before they clashed. And clash they did in Fantastic Four #12 (March 1963) by Stan Lee, Jack Kirby and inks by Dick Ayers, from those fabled days when Kirby hadn't yet settled on the correct number of fingers and toes for the Hulk. In this issue, the Jade Giant flaunts three of each, plus opposable thumbs for a grand total of fourteen digits. Strangely enough, the same number sported by the Thing. That's okay, because there's at least one instance of Mr. Fantastic showing six on one hand in a later issue.

The story opens with the Thing looking natty in a tux, out on the town with his girlfriend Alicia Masters. Within moments, things take a tragi-comic turn as they frequently do in this old Marvel stories-- soldiers on the alert for the Hulk cause a scene, an old man accidentally pokes the Thing, the Thing reacts angrily, attracts the attention of the soldiers, there's a fight as a result of mistaken identity and the Thing is publicly humiliated once again. Why the soldiers are out looking for the Hulk is obvious-- he's a destructive menace. But why their officers sent them out without first briefing them on what the Hulk's actual appearance is something neither Stan Lee nor Jack Kirby care to explain. And if being mistaken for a green monster in purple pants isn't pathetic enough for our orange monster in blue pants, the Thing also forgets his key to the Fantastic Four's special elevator and has to climb up the cables to get home.

None other than General "Thunderbolt" Ross (oddly appearing in an army uniform rather than one from the USAF) then comes to the Baxter Building to recruit the team to fight the Hulk for him. To prove the Hulk's existence, Ross screens some top secret film footage of the Hulk in action, which causes the testosterone-laden male heroes-- including ostensibly mature older genius Reed Richards-- to act out their fantasies of single-handedly defeating the Hulk, while lone female Sue Storm frets about her uselessness. At least until the men decide she's good "for morale." Guess the Thing isn't the only one meeting with humiliation this fine evening.

The issue features the debut of a new whiz-wagon for the gang, the Fantasticar redesigned in-story by Johnny Storm, and featuring one of the many meta-moments Lee and Kirby inserted into the book in those days-- supposedly fans of the team wrote in complaining that the old Fantasticar looked too much like a flying bathtub. The new one is a sleek Kirby creation that gives Ross a military-industrial complex boner. The five rocket to the western desert and fight's on.

The issue features the debut of a new whiz-wagon for the gang, the Fantasticar redesigned in-story by Johnny Storm, and featuring one of the many meta-moments Lee and Kirby inserted into the book in those days-- supposedly fans of the team wrote in complaining that the old Fantasticar looked too much like a flying bathtub. The new one is a sleek Kirby creation that gives Ross a military-industrial complex boner. The five rocket to the western desert and fight's on.

The Hulk is actually a big green herring as it turns out-- the real villain is someone called "the Wrecker" (a likely name) who sabotages our American way of life for his Commie overlords. I don't want to spoil the story's big secret, but the Wrecker turns out to be the guy with the membership card in a communist subversive organization right there in his wallet. Great detective work there, Rick Jones. This leaves the Thing wondering out loud, "Just what the heck was I fighting the Hulk for?" No reason, really, other then the very coolness of Thing versus Hulk, Thing! Oh, and advertising for another hero even if his own title flopped. In their first bout, our boys seem pretty evenly matched, and it's useless Sue Storm who manages to knock out the Wrecker and save the day for everyone. Never underestimate Sue, fellas. The Hulk, weakened by a laser beam, gives up and slinks away to fight another day. So after all that, we don't even get a definitive answer to the question of which hero is muscle supreme in the Marvel universe.

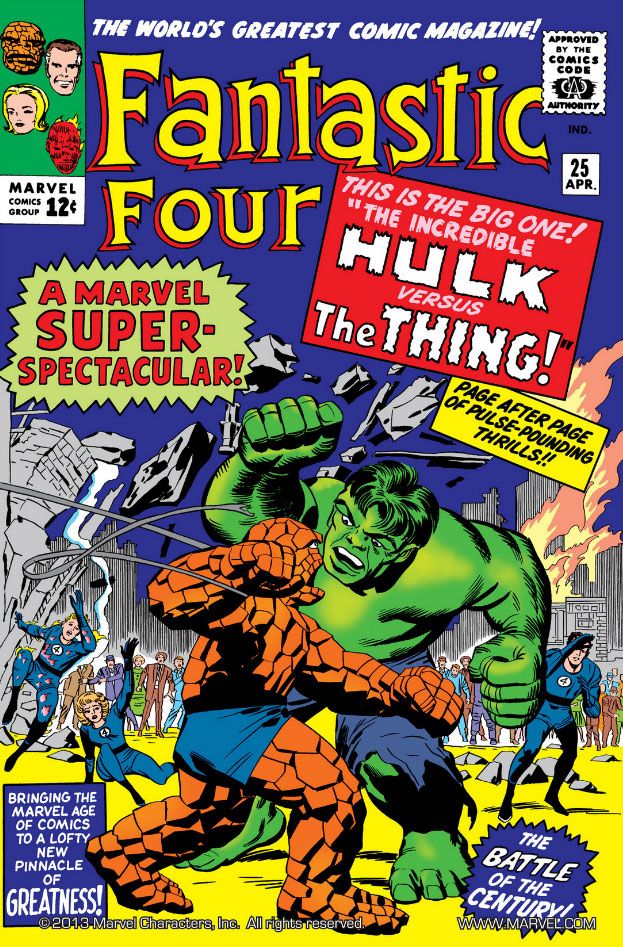

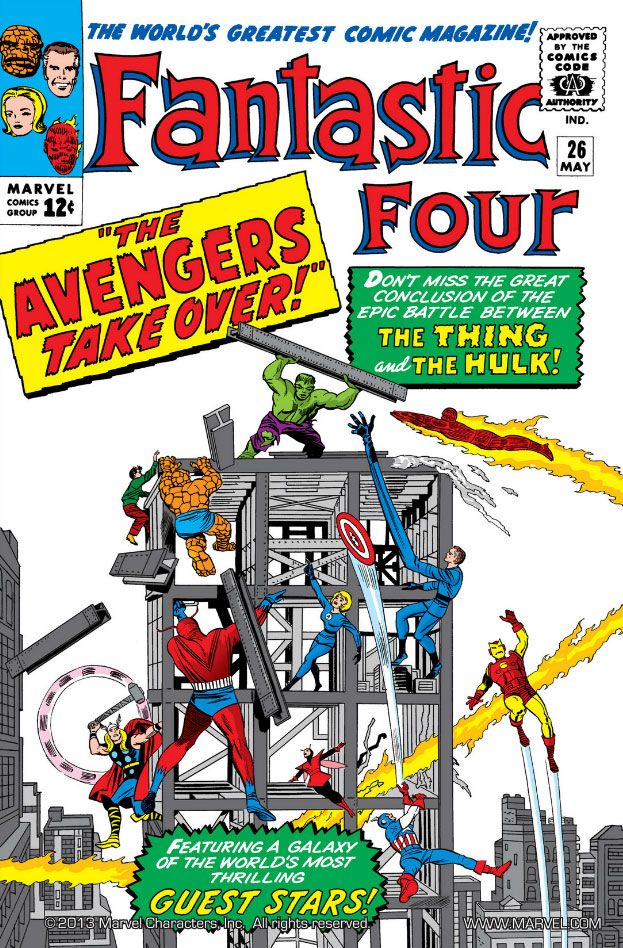

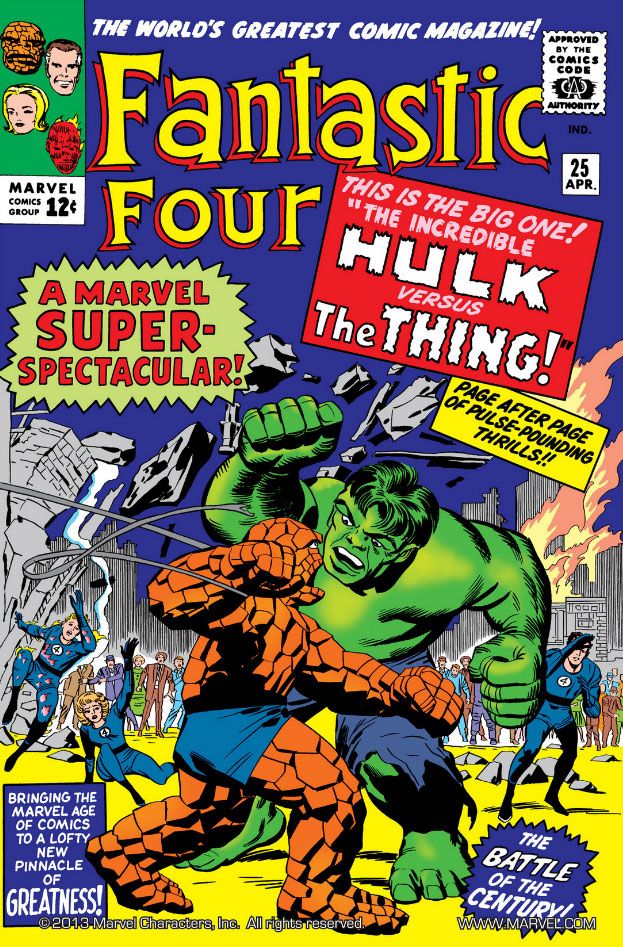

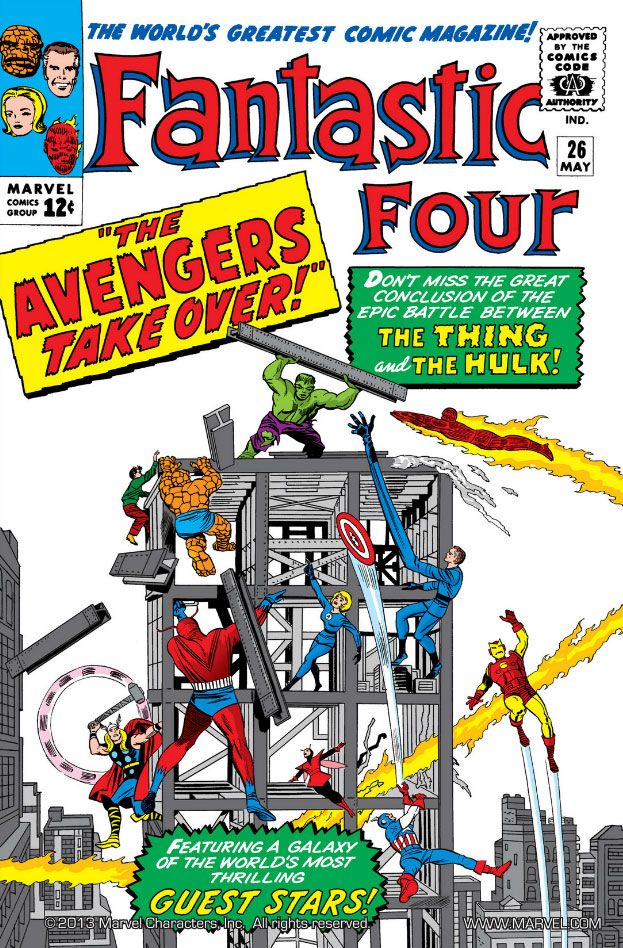

That is until a year later when Marvel published Fantastic Four #25 and 26 (April and May 1964 with George Roussos on inks this time, credited as George Bell), a story so big it sprawls over two complete issues and involves practically every other Marvel hero of the time. I'm guessing it was Lee who crammed all the hyperbolic copy onto the cover of #25, the Man at his carnival barker's best. This is the kind of stuff I've come to associate with the feeling of reading Marvel comics from the 60s and 70s-- a relentless barrage of overblown propaganda, indoctrinating the readers in the Mighty Marvel Mindset with phrases like "PULSE-POUNDING" and "SENSES-SHATTERING" (as if the latter was even remotely desirable). This time the Fantastic Four don't have to go hunting the Hulk-- the big green galoot himself turns up in New York City because he's angry at the Avengers for booting him in favor of Captain America.

I can't blame the Avengers. Who would you rather have on your team anyway-- a rational, intelligent strategist with acrobatic fighting skills and years of war-time experience, or an overly-sensitive rage-aholic with the strength to flatten entire cities? No, you can't choose both. Now imagine how well the Hulk takes your decision and you can see the problem this dilemma presents. As if a vengeful Hulk weren't enough, the FF are fighting amongst themselves as well because the Thing refuses to drink Reed's newest cure for his condition-- which apparently was such a lab accident Reed doubts he can re-create it. Shortly after that, Reed abruptly collapses into a coma and everyone is screwed. The Hulk gives the remaining Fantastics a thorough thumping of the kind world champ Sonny Liston received from 22-year-old Muhammad Ali roughly a month before this issue hit the newsstands. The Human Torch ends up in the hospital and Sue poops out when the Hulk's strength severely taxes her relatively-new invisible forcefield powers. This leaves the Thing to fight alone, which he does for most of the issue until the Hulk finally grinds him down.

Never having been defeated outright before, the Thing spends a moment questioning his purpose in the world. But he figures it out-- as a hero, his job is to take any beating necessary, even if he fails or dies as a result. Once again, it's the Thing doing the world's dirty work, overmatched and underappreciated, a lone man against impossible odds and, unlike Liston, he decides to come out of his corner at the bell.

Never having been defeated outright before, the Thing spends a moment questioning his purpose in the world. But he figures it out-- as a hero, his job is to take any beating necessary, even if he fails or dies as a result. Once again, it's the Thing doing the world's dirty work, overmatched and underappreciated, a lone man against impossible odds and, unlike Liston, he decides to come out of his corner at the bell.

While poignantly scripted by Lee, this is Kirby storytelling, a moment where his contributions as a full-fledged writer-- not simply co-plotter and certainly not merely penciller-- breaks through most obviously. You can't help but feel Kirby working autobiographically here, concerns of an intensely personal nature filtering through the fat line screens of the 1960s four-color printing process. So characteristically Kirby is it, he'd return to it again and again-- most memorably in "The Death Wish of Terrible Turpin" from New Gods #8 (April 1972), but also as a running subtext to the entirety of his run on Kamandi the Last Boy on Earth.

Together, Lee and Kirby develop this theme over the course of #26, where we see Richards attempting to come off his sickbed to help the Thing and the Human Torch flying back into the fray despite being decked out in asbestos bandages from the beating he took in the previous issue. Captain America shows a lot of the heroic stuff Kirby-style as he uses judo he learned in the Army against the Hulk, even though he knows he's involved in a massive weight-class mismatch. So Captain America proves himself as an Avenger, but it's the Thing's example that inspires him and provides the story's beating heart.

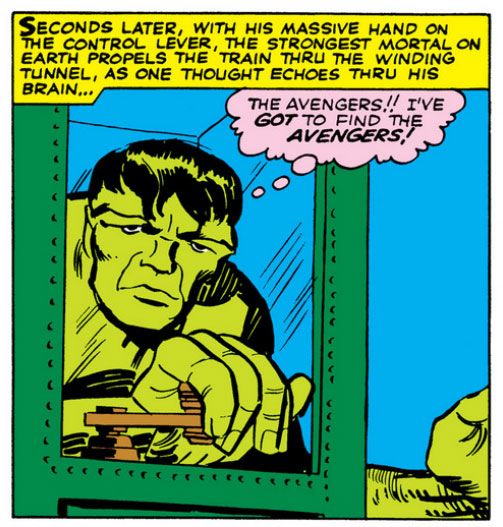

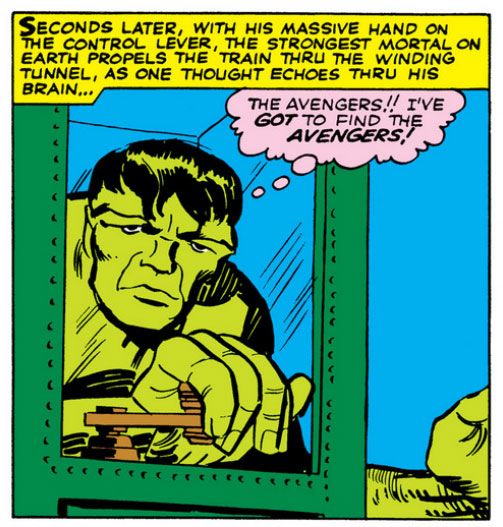

It's a fairly funny story as well, and I don't mean just inadvertently (for example, when the Hulk calls his weaker alter-ego "Bob" Banner for some reason-- we'll cut him some slack; he has a lot on his mind what with needing to file for unemployment and all that). At one point the Thing threatens to use his powers of pathos against the Hulk. My favorite sequence has the Hulk hijack a subway train and drive it to the Avengers' mansion. Kirby treats us to a sweet shot of a mopey Hulk at the controls which reminds me a lot of that Shaquille O'Neal commercial where he's too large for a sporty convertible. I'm pretty sure Lee and Kirby got a huge kick out of tossing in this particular scene.

It's a fairly funny story as well, and I don't mean just inadvertently (for example, when the Hulk calls his weaker alter-ego "Bob" Banner for some reason-- we'll cut him some slack; he has a lot on his mind what with needing to file for unemployment and all that). At one point the Thing threatens to use his powers of pathos against the Hulk. My favorite sequence has the Hulk hijack a subway train and drive it to the Avengers' mansion. Kirby treats us to a sweet shot of a mopey Hulk at the controls which reminds me a lot of that Shaquille O'Neal commercial where he's too large for a sporty convertible. I'm pretty sure Lee and Kirby got a huge kick out of tossing in this particular scene.

Speaking of the Avengers, they finally make the scene and flub their fight against the Hulk because there are just too many costumed clowns running around. It gets worse when the fully recovered Fantastic Four pitch in, and then the two teams start a jurisdictional squabble. Reed Richards suggest the Thing decide whether or not the two teams join forces since he's the one who's been doing most of the fighting and carrying the story on his rocky shoulders.

The Hulk and the Thing come together atop an under-construction building and trade blows. Teenager Rick Jones pulls a Sue Storm and saves the day by tossing a gamma pill into the Hulk's mouth. The Hulk falls into the river, but it's Bruce Banner its currents sweep away.

The Hulk and the Thing come together atop an under-construction building and trade blows. Teenager Rick Jones pulls a Sue Storm and saves the day by tossing a gamma pill into the Hulk's mouth. The Hulk falls into the river, but it's Bruce Banner its currents sweep away.

Two complete issues probably seemed overblown in 1964, but in our current era of drawn-out, marketing-driven storytelling I'm amazed how economically Lee and Kirby run through this plot. Today's version would require an editor's meeting of a dozen or more thinkers to plan it (they'd spread it over an entire summer's or even a year's worth of titles priced at $2.99 or $3.99 each, interrupting whatever storylines the various writers have going), feature some supposedly-beloved secondary character like Rick Jones having his arms ripped off on-panel (the blog-o-sphere goes wild!) and climax in an over-sized special edition. Entertainment Weekly would give it a B+ and declare it "the superhero epic of the season" while praising it for the repeated flashbacks to Bruce Banner's abusive childhood. They'd also go nuts over the photo-realistic art, consisting mainly of pages of wide panels stacked broken by frequent full-body portraits of various involved characters, all of which would quickly show up in online auctions with hefty price-tags.

Lee and Kirby neatly pack it all into two standard-sized issues, minus any hint of gore but with plenty of action and characterization. It also lacks today's trendy Joss Whedon-style dialogue where every character is a quip-making machine, but apologizes by having the Thing call Thor a "lantern-jawed, long-haired lummox."

First, you have the Thing. A mouthy orange rock-man, the muscle and the ever-lovin' heart of the Fantastic Four. The Thing was essentially nice. Who the heck could hate the Thing? Then, you have the Hulk. In the 1960s, at least for a time, the Hulk had a command of language beyond simple statements in favor of smashing, or admonishments to puny humans to leave him alone. He was an anti-hero hearkening back to Marvel's early years when they put out comics where Namor would show up pissed off for whatever reason and start tearing up the place. Namor was the kind of dangerous character you rooted for only because he was fighting Nazis (only other Nazis root for Nazis), mad scientists or because he was like your own repressed child-id striking back at adult authority figures-- otherwise, Namor was angry specifically at you, the reader, for existing on land. It's a similar story with the Hulk and Space Age-era Communists and outright villains.

With two opposing forces like these in a single comic book universe, it was only a matter of time before they clashed. And clash they did in Fantastic Four #12 (March 1963) by Stan Lee, Jack Kirby and inks by Dick Ayers, from those fabled days when Kirby hadn't yet settled on the correct number of fingers and toes for the Hulk. In this issue, the Jade Giant flaunts three of each, plus opposable thumbs for a grand total of fourteen digits. Strangely enough, the same number sported by the Thing. That's okay, because there's at least one instance of Mr. Fantastic showing six on one hand in a later issue.

With two opposing forces like these in a single comic book universe, it was only a matter of time before they clashed. And clash they did in Fantastic Four #12 (March 1963) by Stan Lee, Jack Kirby and inks by Dick Ayers, from those fabled days when Kirby hadn't yet settled on the correct number of fingers and toes for the Hulk. In this issue, the Jade Giant flaunts three of each, plus opposable thumbs for a grand total of fourteen digits. Strangely enough, the same number sported by the Thing. That's okay, because there's at least one instance of Mr. Fantastic showing six on one hand in a later issue.The story opens with the Thing looking natty in a tux, out on the town with his girlfriend Alicia Masters. Within moments, things take a tragi-comic turn as they frequently do in this old Marvel stories-- soldiers on the alert for the Hulk cause a scene, an old man accidentally pokes the Thing, the Thing reacts angrily, attracts the attention of the soldiers, there's a fight as a result of mistaken identity and the Thing is publicly humiliated once again. Why the soldiers are out looking for the Hulk is obvious-- he's a destructive menace. But why their officers sent them out without first briefing them on what the Hulk's actual appearance is something neither Stan Lee nor Jack Kirby care to explain. And if being mistaken for a green monster in purple pants isn't pathetic enough for our orange monster in blue pants, the Thing also forgets his key to the Fantastic Four's special elevator and has to climb up the cables to get home.

None other than General "Thunderbolt" Ross (oddly appearing in an army uniform rather than one from the USAF) then comes to the Baxter Building to recruit the team to fight the Hulk for him. To prove the Hulk's existence, Ross screens some top secret film footage of the Hulk in action, which causes the testosterone-laden male heroes-- including ostensibly mature older genius Reed Richards-- to act out their fantasies of single-handedly defeating the Hulk, while lone female Sue Storm frets about her uselessness. At least until the men decide she's good "for morale." Guess the Thing isn't the only one meeting with humiliation this fine evening.

The issue features the debut of a new whiz-wagon for the gang, the Fantasticar redesigned in-story by Johnny Storm, and featuring one of the many meta-moments Lee and Kirby inserted into the book in those days-- supposedly fans of the team wrote in complaining that the old Fantasticar looked too much like a flying bathtub. The new one is a sleek Kirby creation that gives Ross a military-industrial complex boner. The five rocket to the western desert and fight's on.

The issue features the debut of a new whiz-wagon for the gang, the Fantasticar redesigned in-story by Johnny Storm, and featuring one of the many meta-moments Lee and Kirby inserted into the book in those days-- supposedly fans of the team wrote in complaining that the old Fantasticar looked too much like a flying bathtub. The new one is a sleek Kirby creation that gives Ross a military-industrial complex boner. The five rocket to the western desert and fight's on. The Hulk is actually a big green herring as it turns out-- the real villain is someone called "the Wrecker" (a likely name) who sabotages our American way of life for his Commie overlords. I don't want to spoil the story's big secret, but the Wrecker turns out to be the guy with the membership card in a communist subversive organization right there in his wallet. Great detective work there, Rick Jones. This leaves the Thing wondering out loud, "Just what the heck was I fighting the Hulk for?" No reason, really, other then the very coolness of Thing versus Hulk, Thing! Oh, and advertising for another hero even if his own title flopped. In their first bout, our boys seem pretty evenly matched, and it's useless Sue Storm who manages to knock out the Wrecker and save the day for everyone. Never underestimate Sue, fellas. The Hulk, weakened by a laser beam, gives up and slinks away to fight another day. So after all that, we don't even get a definitive answer to the question of which hero is muscle supreme in the Marvel universe.

That is until a year later when Marvel published Fantastic Four #25 and 26 (April and May 1964 with George Roussos on inks this time, credited as George Bell), a story so big it sprawls over two complete issues and involves practically every other Marvel hero of the time. I'm guessing it was Lee who crammed all the hyperbolic copy onto the cover of #25, the Man at his carnival barker's best. This is the kind of stuff I've come to associate with the feeling of reading Marvel comics from the 60s and 70s-- a relentless barrage of overblown propaganda, indoctrinating the readers in the Mighty Marvel Mindset with phrases like "PULSE-POUNDING" and "SENSES-SHATTERING" (as if the latter was even remotely desirable). This time the Fantastic Four don't have to go hunting the Hulk-- the big green galoot himself turns up in New York City because he's angry at the Avengers for booting him in favor of Captain America.

I can't blame the Avengers. Who would you rather have on your team anyway-- a rational, intelligent strategist with acrobatic fighting skills and years of war-time experience, or an overly-sensitive rage-aholic with the strength to flatten entire cities? No, you can't choose both. Now imagine how well the Hulk takes your decision and you can see the problem this dilemma presents. As if a vengeful Hulk weren't enough, the FF are fighting amongst themselves as well because the Thing refuses to drink Reed's newest cure for his condition-- which apparently was such a lab accident Reed doubts he can re-create it. Shortly after that, Reed abruptly collapses into a coma and everyone is screwed. The Hulk gives the remaining Fantastics a thorough thumping of the kind world champ Sonny Liston received from 22-year-old Muhammad Ali roughly a month before this issue hit the newsstands. The Human Torch ends up in the hospital and Sue poops out when the Hulk's strength severely taxes her relatively-new invisible forcefield powers. This leaves the Thing to fight alone, which he does for most of the issue until the Hulk finally grinds him down.

Never having been defeated outright before, the Thing spends a moment questioning his purpose in the world. But he figures it out-- as a hero, his job is to take any beating necessary, even if he fails or dies as a result. Once again, it's the Thing doing the world's dirty work, overmatched and underappreciated, a lone man against impossible odds and, unlike Liston, he decides to come out of his corner at the bell.

Never having been defeated outright before, the Thing spends a moment questioning his purpose in the world. But he figures it out-- as a hero, his job is to take any beating necessary, even if he fails or dies as a result. Once again, it's the Thing doing the world's dirty work, overmatched and underappreciated, a lone man against impossible odds and, unlike Liston, he decides to come out of his corner at the bell. While poignantly scripted by Lee, this is Kirby storytelling, a moment where his contributions as a full-fledged writer-- not simply co-plotter and certainly not merely penciller-- breaks through most obviously. You can't help but feel Kirby working autobiographically here, concerns of an intensely personal nature filtering through the fat line screens of the 1960s four-color printing process. So characteristically Kirby is it, he'd return to it again and again-- most memorably in "The Death Wish of Terrible Turpin" from New Gods #8 (April 1972), but also as a running subtext to the entirety of his run on Kamandi the Last Boy on Earth.

Together, Lee and Kirby develop this theme over the course of #26, where we see Richards attempting to come off his sickbed to help the Thing and the Human Torch flying back into the fray despite being decked out in asbestos bandages from the beating he took in the previous issue. Captain America shows a lot of the heroic stuff Kirby-style as he uses judo he learned in the Army against the Hulk, even though he knows he's involved in a massive weight-class mismatch. So Captain America proves himself as an Avenger, but it's the Thing's example that inspires him and provides the story's beating heart.

It's a fairly funny story as well, and I don't mean just inadvertently (for example, when the Hulk calls his weaker alter-ego "Bob" Banner for some reason-- we'll cut him some slack; he has a lot on his mind what with needing to file for unemployment and all that). At one point the Thing threatens to use his powers of pathos against the Hulk. My favorite sequence has the Hulk hijack a subway train and drive it to the Avengers' mansion. Kirby treats us to a sweet shot of a mopey Hulk at the controls which reminds me a lot of that Shaquille O'Neal commercial where he's too large for a sporty convertible. I'm pretty sure Lee and Kirby got a huge kick out of tossing in this particular scene.

It's a fairly funny story as well, and I don't mean just inadvertently (for example, when the Hulk calls his weaker alter-ego "Bob" Banner for some reason-- we'll cut him some slack; he has a lot on his mind what with needing to file for unemployment and all that). At one point the Thing threatens to use his powers of pathos against the Hulk. My favorite sequence has the Hulk hijack a subway train and drive it to the Avengers' mansion. Kirby treats us to a sweet shot of a mopey Hulk at the controls which reminds me a lot of that Shaquille O'Neal commercial where he's too large for a sporty convertible. I'm pretty sure Lee and Kirby got a huge kick out of tossing in this particular scene.Speaking of the Avengers, they finally make the scene and flub their fight against the Hulk because there are just too many costumed clowns running around. It gets worse when the fully recovered Fantastic Four pitch in, and then the two teams start a jurisdictional squabble. Reed Richards suggest the Thing decide whether or not the two teams join forces since he's the one who's been doing most of the fighting and carrying the story on his rocky shoulders.

The Hulk and the Thing come together atop an under-construction building and trade blows. Teenager Rick Jones pulls a Sue Storm and saves the day by tossing a gamma pill into the Hulk's mouth. The Hulk falls into the river, but it's Bruce Banner its currents sweep away.

The Hulk and the Thing come together atop an under-construction building and trade blows. Teenager Rick Jones pulls a Sue Storm and saves the day by tossing a gamma pill into the Hulk's mouth. The Hulk falls into the river, but it's Bruce Banner its currents sweep away.Two complete issues probably seemed overblown in 1964, but in our current era of drawn-out, marketing-driven storytelling I'm amazed how economically Lee and Kirby run through this plot. Today's version would require an editor's meeting of a dozen or more thinkers to plan it (they'd spread it over an entire summer's or even a year's worth of titles priced at $2.99 or $3.99 each, interrupting whatever storylines the various writers have going), feature some supposedly-beloved secondary character like Rick Jones having his arms ripped off on-panel (the blog-o-sphere goes wild!) and climax in an over-sized special edition. Entertainment Weekly would give it a B+ and declare it "the superhero epic of the season" while praising it for the repeated flashbacks to Bruce Banner's abusive childhood. They'd also go nuts over the photo-realistic art, consisting mainly of pages of wide panels stacked broken by frequent full-body portraits of various involved characters, all of which would quickly show up in online auctions with hefty price-tags.

Lee and Kirby neatly pack it all into two standard-sized issues, minus any hint of gore but with plenty of action and characterization. It also lacks today's trendy Joss Whedon-style dialogue where every character is a quip-making machine, but apologizes by having the Thing call Thor a "lantern-jawed, long-haired lummox."

And yes, Sue, no one was injured. Except the Thing and your brother, Johnny (twice!). And probably Iron Man when the Hulk head-butted him right in the chest.

Labels:

Dick Ayers,

Fantastic Four,

George Bell,

good art,

good comics,

Hulk,

Jack Kirby,

Marvel,

Stan Lee,

Thing,

vintage comics

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)