X-Men #94 (August 1975) was the first X-comic I owned. A friend's mother worked for a regional magazine distributor and he got the leftovers. This kid had piles of comics in his room, but he kept the X-Men issues in a cabinet in the living room for whatever reason. Probably anti-mutant bigotry on his part. After all these years I can't remember why he decided to sell some comics to me that day, nor can I remember why I wanted to buy them. I liked comics, knew the difference between Jack Kirby and Alex Toth, loved Joe Kubert's art and had already discovered Al Williamson. I just don't remember being comics crazy, but I was a junior high sequential art connoisseur of sorts because I loved drawing.

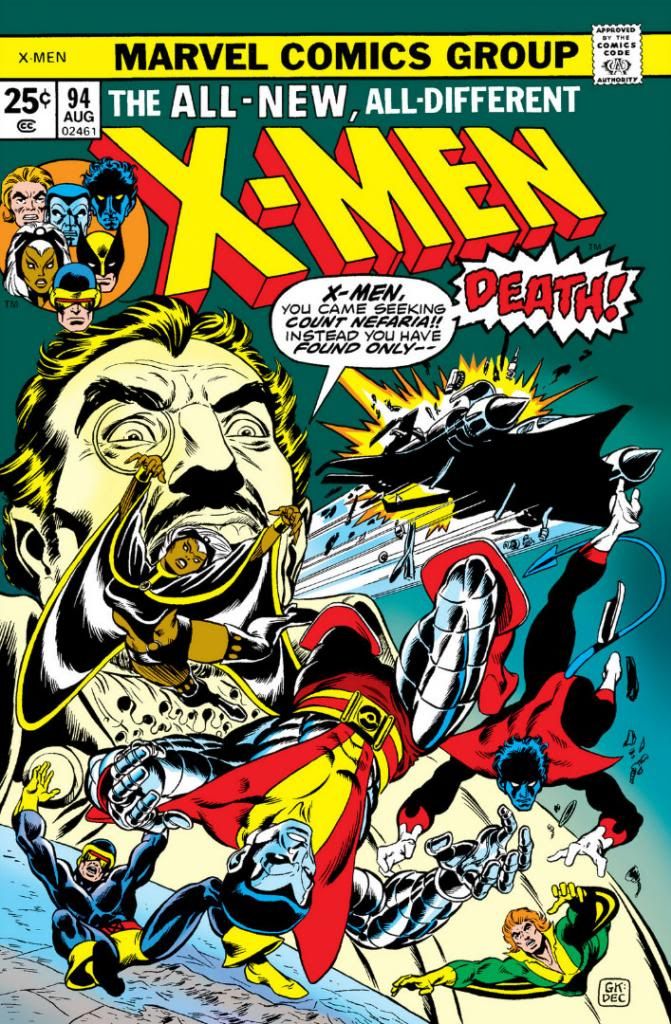

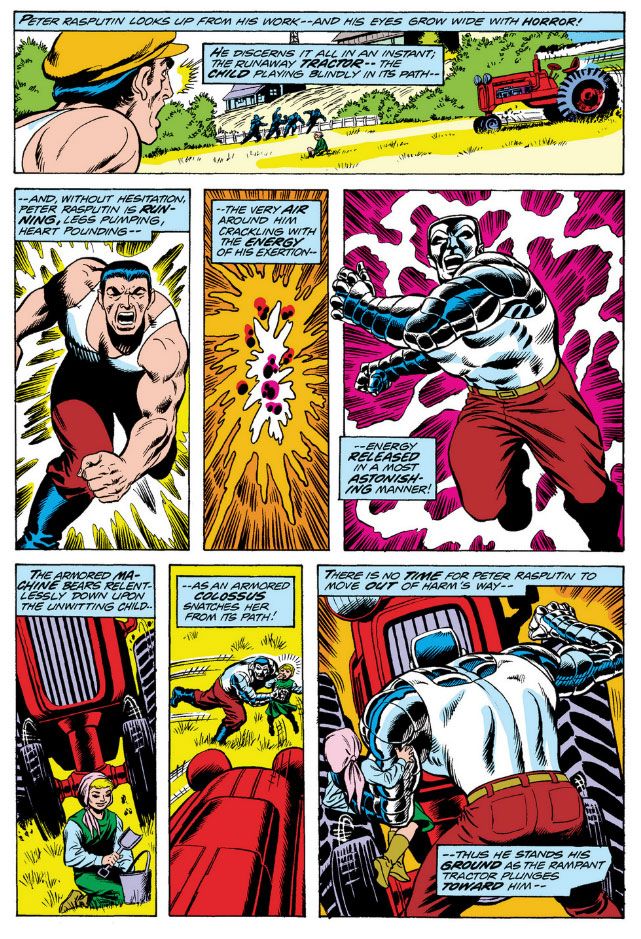

So years later, I'm going to claim it was the Gil Kane/Dave Cockrum cover that caught my fancy. Even now, this cover impresses with its high (literally) drama and contorted heroes hurtling earthward to their deaths. Well, except for Banshee, who seems to be flying to the rescue. Poor Storm has completely forgotten she knows how to ride the winds-- and note Wolverine and Thunderbird don't even rate appearances! Even without those two adding to the excitement, it looks kind of like Count Nefaria (the guy with the giant white head) is barfing mutants. That characteristic Kane up-the-spout shot of Nefaria's face influenced the heck out of me for the next few years and I drew noses from that angle blacked in so I wouldn't have to work out the difficult low-angled perspective of the various nasal planes. It seemed an elegantly simple solution to a drawing problem that had me stumped. And you absolutely cannot beat the energy of Colossus in the foreground, boldly sporting primary colors of red and yellow. Barfed or falling, that figure practically bursts from the picture plane and lands in your lap. I probably bought the comics because I wanted to draw this particular cover. I still do. Good gravy, I love me some Gil Kane!

My friend and I worked out a little deal where I paid him all the money I had in my pocket with a promise for more. I think the original deal was supposed to be twenty bucks for a stack of books that, amazingly (or uncannily, if you will) included the first five or six issues of the "All-New, All-Different" X-Men. In the end, I forked over a grand total of fourteen dollars and the use of my left-handed baseball glove in P.E. a couple of weeks later. By the time my pal and I completed the transaction on that long-ago spring day, I was in completely in goo-goo-ga-ga love with comic books in general and X-Men in particular.

Enough biography. Let's read!

"The Doomsmith Scenario" introduces us to a man who has access to a matter transporter (maybe he invented it; the story never says where it comes from) and has also used some kind of genetic technology to mutate humans into anthropomorphic animal weirdos (which, admittedly, is a process that has fewer immediately-apparent practical applications). Rather than launch a second Industrial Revolution by transforming the travel, transportation and medical industries and reaping billions, if not trillions, in ongoing profits, all he can think to do with this technology is invade a military base to hold the world hostage for a one-time payoff. Granted, that involves each nation paying as much as it's capable, but it's still taking a huge risk versus a guarantee of unprecedented wealth if he just patents his tech and sells, sells, sells.

His name is Count Nefaria, and he is one of the most visually boring antagonists I’ve ever seen. I believe these days he's some kind of immortal energy being, but when this book hit the spinner racks, Nefaria was just a goateed twerp in a suit with a ruffled shirt and evening cloak, a second-rate Bela Lugosi impersonator. Off-the-rack, ready-to-wear, one-size-fits-all villainy. His name essentially means Count Bad Guy, just to further illustrate how little effort went into his creation. We can argue that dumb names are a hallmark of ol' Marvel. I certainly will... Doctor Doom. But to look at the magnificent Doom is to understand Nefaria's generic quality. The Avengers dealt with the Count in #13 (February 1965) of their own book-- the synopsis of which makes the story seem completely interchangeable with just about any found in other Marvel team titles of the era-- and the unfortunate X-Men get stuck with him in the first regular issue of their revamped title.

Our kid Nefaria and his Ani-Men invade Valhalla Mountain, home of NORAD’s super-sensitive defense center. Despite looking like refugees from a line of He-Man knock-off toys, the Ani-Morphs or Ani-Men (one of whom is female, by the way) quickly subdue thousands of armed soldiers and military police who don’t simply shoot them on sight.

The Ani-Men have the advantage of surprise for a few minutes, plus they're fast and strong. That's more than enough to defeat the first bunch of uniformed slackers. After that the entire base is on alert, yet the troops commit themselves piecemeal and not one soldier or airman gets off a shot despite being armed to the hilt. They don't even try to shoot. They must have been trained to use their rifles as clubs, and badly at that. After this inexplicably incompetent response by our armed forces, Nefaria gasses everyone else to sleep. It's just that easy for our tuxedo-wearing criminal genius. I understand that in 1975, our armed forces were doing some serious soul-searching as the country emerged from the prolonged humiliation of the Vietnam War, but even the Mayaguez incident had a more satisfying military conclusion than this Nefaria deal.

Of course, if we closed this plot hole we'd have a five page story where the X-Men watch a news report about a strange incident where Nefaria and the Ani-Men died in a hail of gunfire, and the rest of the comic would consist of pre-Thor Journey Into Mystery reprints. That would never do, so the men and women guarding the United States' most important and secure military installation allow themselves to get their asses handed to them and, with the Avengers conveniently shelved, it’s up to our new X-Men to fly in and try to save the world.

So years later, I'm going to claim it was the Gil Kane/Dave Cockrum cover that caught my fancy. Even now, this cover impresses with its high (literally) drama and contorted heroes hurtling earthward to their deaths. Well, except for Banshee, who seems to be flying to the rescue. Poor Storm has completely forgotten she knows how to ride the winds-- and note Wolverine and Thunderbird don't even rate appearances! Even without those two adding to the excitement, it looks kind of like Count Nefaria (the guy with the giant white head) is barfing mutants. That characteristic Kane up-the-spout shot of Nefaria's face influenced the heck out of me for the next few years and I drew noses from that angle blacked in so I wouldn't have to work out the difficult low-angled perspective of the various nasal planes. It seemed an elegantly simple solution to a drawing problem that had me stumped. And you absolutely cannot beat the energy of Colossus in the foreground, boldly sporting primary colors of red and yellow. Barfed or falling, that figure practically bursts from the picture plane and lands in your lap. I probably bought the comics because I wanted to draw this particular cover. I still do. Good gravy, I love me some Gil Kane!

My friend and I worked out a little deal where I paid him all the money I had in my pocket with a promise for more. I think the original deal was supposed to be twenty bucks for a stack of books that, amazingly (or uncannily, if you will) included the first five or six issues of the "All-New, All-Different" X-Men. In the end, I forked over a grand total of fourteen dollars and the use of my left-handed baseball glove in P.E. a couple of weeks later. By the time my pal and I completed the transaction on that long-ago spring day, I was in completely in goo-goo-ga-ga love with comic books in general and X-Men in particular.

"The Doomsmith Scenario" introduces us to a man who has access to a matter transporter (maybe he invented it; the story never says where it comes from) and has also used some kind of genetic technology to mutate humans into anthropomorphic animal weirdos (which, admittedly, is a process that has fewer immediately-apparent practical applications). Rather than launch a second Industrial Revolution by transforming the travel, transportation and medical industries and reaping billions, if not trillions, in ongoing profits, all he can think to do with this technology is invade a military base to hold the world hostage for a one-time payoff. Granted, that involves each nation paying as much as it's capable, but it's still taking a huge risk versus a guarantee of unprecedented wealth if he just patents his tech and sells, sells, sells.

His name is Count Nefaria, and he is one of the most visually boring antagonists I’ve ever seen. I believe these days he's some kind of immortal energy being, but when this book hit the spinner racks, Nefaria was just a goateed twerp in a suit with a ruffled shirt and evening cloak, a second-rate Bela Lugosi impersonator. Off-the-rack, ready-to-wear, one-size-fits-all villainy. His name essentially means Count Bad Guy, just to further illustrate how little effort went into his creation. We can argue that dumb names are a hallmark of ol' Marvel. I certainly will... Doctor Doom. But to look at the magnificent Doom is to understand Nefaria's generic quality. The Avengers dealt with the Count in #13 (February 1965) of their own book-- the synopsis of which makes the story seem completely interchangeable with just about any found in other Marvel team titles of the era-- and the unfortunate X-Men get stuck with him in the first regular issue of their revamped title.

Our kid Nefaria and his Ani-Men invade Valhalla Mountain, home of NORAD’s super-sensitive defense center. Despite looking like refugees from a line of He-Man knock-off toys, the Ani-Morphs or Ani-Men (one of whom is female, by the way) quickly subdue thousands of armed soldiers and military police who don’t simply shoot them on sight.

The Ani-Men have the advantage of surprise for a few minutes, plus they're fast and strong. That's more than enough to defeat the first bunch of uniformed slackers. After that the entire base is on alert, yet the troops commit themselves piecemeal and not one soldier or airman gets off a shot despite being armed to the hilt. They don't even try to shoot. They must have been trained to use their rifles as clubs, and badly at that. After this inexplicably incompetent response by our armed forces, Nefaria gasses everyone else to sleep. It's just that easy for our tuxedo-wearing criminal genius. I understand that in 1975, our armed forces were doing some serious soul-searching as the country emerged from the prolonged humiliation of the Vietnam War, but even the Mayaguez incident had a more satisfying military conclusion than this Nefaria deal.

Of course, if we closed this plot hole we'd have a five page story where the X-Men watch a news report about a strange incident where Nefaria and the Ani-Men died in a hail of gunfire, and the rest of the comic would consist of pre-Thor Journey Into Mystery reprints. That would never do, so the men and women guarding the United States' most important and secure military installation allow themselves to get their asses handed to them and, with the Avengers conveniently shelved, it’s up to our new X-Men to fly in and try to save the world.

Which they eventually do, but not before Cyclops spends an entire night roaming the halls of the mansion and bellowing his despair to the world, the original X-Men say a tear-filled farewell and a training montage where Thunderbird injures himself and Cyclops plays drill sergeant. Since Chris Claremont takes a little time in his dialogue and thought-balloons to give both men clear motivations for what they do and how they act (Thunderbird is insecure, Cyclops is seasoned professional who has seen too many deaths and injuries in his time), the conflict between them works better than the seemingly random arguments that plagued Giant Size X-Men #1, where characters sniped at each other on practically every page and with no good reason. It also pays major dividends in X-Men #95, but that’s a story for another day.

Penciller Dave Cockrum already had experience with group books, having worked on stories featuring the Legion of Superheroes in Superboy over at DC, and he co-created Nightcrawler, Storm and Colossus for this book. Oh, and he drew the aforementioned Giant Size. You'd imagine drawing a living island would tax a guy's creative faculties. Not Cockrum's. And here? Wow, the man just absolutely cuts loose. He must have wrecked his drawing hand filling panels with detailed backgrounds-- his Valhalla features a gargantuan situation room with elevated walkways between digital maps that must be hundreds of feet high to judge by the teensy-tiny antlike figures teeming all over.

I remember being especially impressed by the training sequence and a collage-like one-page panel centered around Cyclops’s giant shouting head. I copied that head line-for-line on notebook paper dozens of times over the next few years, always hoping to glean those Cockrum art secrets. With the fine-lined inking of Bob McLeod giving the figures a bit of roundness and generally introducing a little bit of a Neal Adams-vibe, Cockrum's dynamic art dazzles. It's pretty. I mean, X-Men #94 has some of the prettiest art of its era. I look at it and I feel joy.

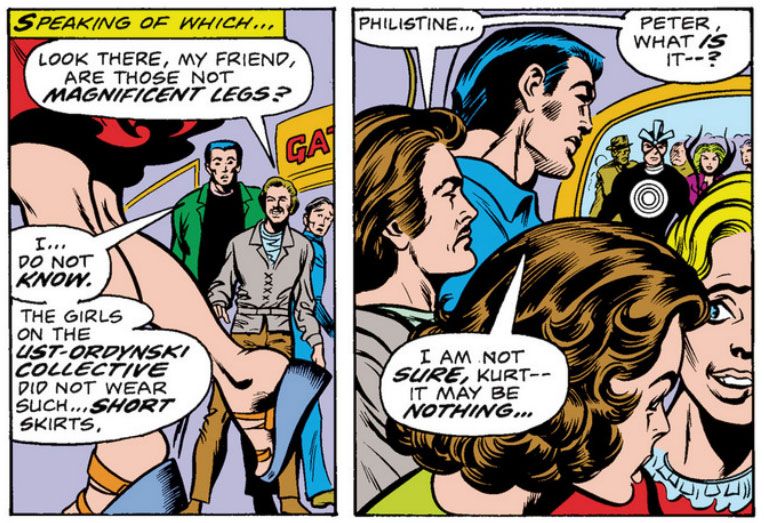

Part of that joy comes from the absurdity of it all. The first half of this book tends towards the talky, which leads to what I think of as a very fun kind of dissonance, like having a company of acrobats in spangled costumes perform Arthur Miller. At one point, angry Japanese hero Sunfire scolds Professor X starting in the X-Mansion living room, but concludes his rant thousands of feet in the air above it. All alone. Well, the Professor is a telepath, so he probably read Sunfire's thoughts or something. When Dave Cockrum provides the acrobats at least you’re getting a primo Cirque du Soleil version of Death of a Salesman. Come to think of it, I’d pay good money to see that.

Since these are by far the best and most entertaining parts of the book, I kind of get the idea Chris Claremont would have been content to have his characters actually hang out around the mansion and watch Nefaria die a pathetic death on television while carrying on various conversations about their feelings and why they're sticking with Professor X. Cyclops may look a little ridiculous expressing his essential dilemma, but at least Claremont gives him one. All these years later, it's easy (and fun!) to parody Chris Claremont's more precious elements (many have, including this blogger) which would eventually overwhelm the book, but the man knew how to invest his audience in the characters and their dilemmas in a way that obsessed readers as never before. When I was 14 years old, I was more emotionally involved in Kitty Pryde and Dani Moonstar than I was in the flesh-and-blood kids of the same age surrounding me at school, and Claremont made it good to feel that way.

But oh yeah-- superheroics! Let's get back to Count Nekot Wafer. After the tearful goodbyes and character-building, the X-Men finally get the call to action. With almost all the pages already used up, the story ends on a cliffhanger, the X-Men falling to their apparent deaths as the result of a “sonic disrupter” Count Nefaria finds in Valhalla’s arsenal. A sonic disrupter is a magical death ray that can disintegrate a supersonic aircraft but leave its passengers intact. Pretty selective! And yet we had to settle for a tie in Southeast Asia.

You can’t tell me any country that can produce a weapon like that and surround it with thousands of armed troops is going to tumble its nuclear warfare nerve center to a ragtag group even Dr. Moreau would discard as failures. Then again, what is Marvel paying all its mutants for? We’ve got the colorful suits, we’ve got Colossus and Storm and Wolverine. Might as well use ‘em!