Piotr Nikolaievitch was born on the Ust-Ordynski collective farm in Siberia. At some point in his early teens he manifested an unusual power-- he could transmute his flesh to living metal, increasing his strength to that of one hundred Stakhanovites. Soon the young man began producing several times his daily quota, which benefited his comrades and the state greatly. And it was there in the beautiful wheat fields of his motherland Piotr Nikolaievitch attracted the attention of noted capitalist psychic Professor Charles Xavier, who, as leader of a team of superheroes and despite his counter-revolutionary upbringing, had become something of a champion of collectivism (albeit allowing his charges to sport outlandish, individualistic garb). The Professor appealed to young Piotr's desire to learn to harness his powers in the interest of the workers of the world. And so it was the strapping lad left the farm and dared the decadent West.

The state began collectivizing agriculture with the First Five-Year Plan, which called for the organization of 20 percent of arable land into collectives. The Central Committee decided in 1930 to extend this to most of the country's grain-producing areas. Stalin took a hand with his Urals-Siberian Method, which essentially forced the farming people of those regions to surrender their grain to the state. Stalin's civil servants also seized farm equipment and livestock, their slogan being "Eliminate the kulaks as a class!" The peasantry resisted. A kind of civil war erupted, with peasants killing livestock rather than surrender it, but forty years later in Giant Size X-Men #1 (May 1975), written by Len Wein and illustrated by Dave Cockrum, readers find the Rasputins living a Spartan yet idyllic existence. By then Nikita Khruschev had denounced Stalin himself in his famous 1954 "Secret Speech" to the Communist Party's Twentieth Congress, the Cuban Missile Crisis had come and gone, also Czechoslovakia, the Vietnam War and the world relaxed a little bit during the thaw era under presidents Richard M. Nixon and Gerald Ford. The time was right for a nice boy like Piotr to leave the collective and make his mark in American superhero funnybooks.

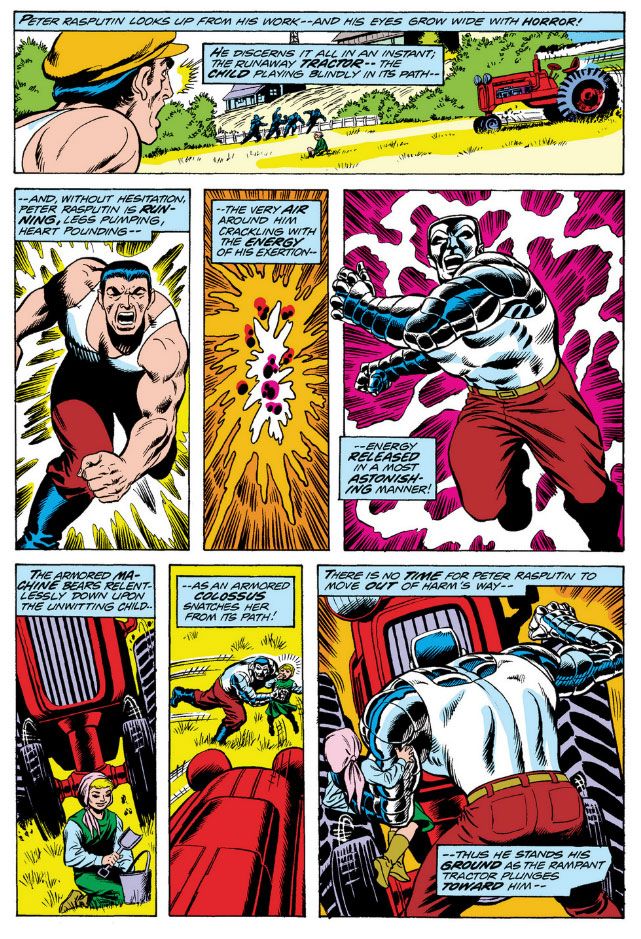

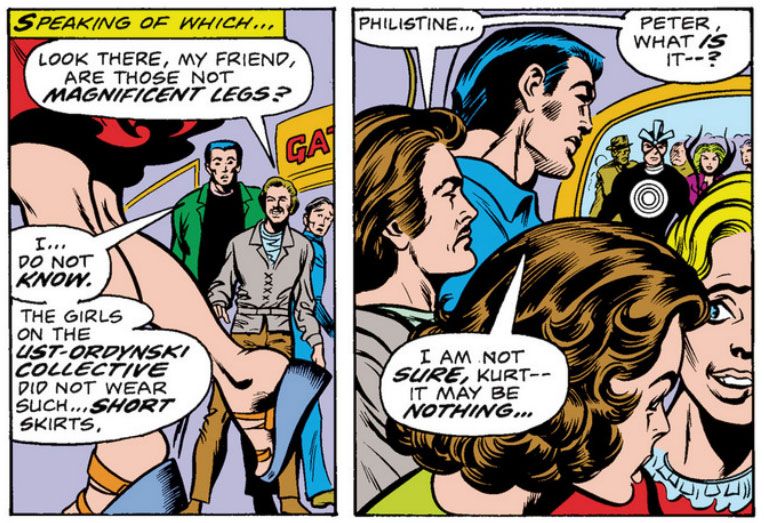

Compared to previous comic book portrayals of communist countries as Orwellian nightmare realms, this new view startles in its National Geographic picturesqueness. Whether in the west or inside the communist sphere, farming remains a dangerous business, however, and Wein presents a convenient tractor accident by way of demonstrating Colossus' powers. The raw, farmboy version of Colossus comes across as kind of a Soviet Li'l Abner in his first appearance and again in X-Men 97 (February 1976) where he and his pal Nightcrawler-- who at this point in his character history uses an "image inducer" to disguise his natural blue-furred appearance-- engage in a little girl-watching. Chris Claremont provides a little fish-out-of-water humor, which artist Cockrum emphasizes with a perfectly chosen "camera" angle.

It's more a cultural moment rather than a political one. Claremont doesn't have Colossus denounce western immorality. Rather, Claremont has the lad make it more personal level, as a young man who has lived a very sheltered sort of existence-- not much different than some guy from a ranch in Montana, for example-- encountering a flash of skin for the first time. Colossus isn't sure of it, but he's learning.

Colossus' home country lasted just over a quarter century more before its economic and political systems could no longer sustain themselves. At that point, the USSR collapsed and divided itself into independent nations. The Cold War had ended, leaving the world with ever-more complex and confusing struggles, but these vintage X-Men comics capture a moment in geopolitical history when two vast powers with ostensibly opposite philosophies faced off through diplomacy and proxy wars across the globe, but the comic book creators from the English-speaking one were willing to humanize the foe and add nuance to their portrayals of our differences.

A few years before Piotr Nikolaievitch would more than likely have been a member of some commie bunch of X-Men counterparts the home team would fight to prevent some kind of moon shot sabotage or balance-of-power altering assassination. Star Trek's Pavel Chekov prefigures Colossus' positive portrayal (even as the show's Klingons exploited the old commie/Cossack/Mongol horde tropes), but during the Seventies and before the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and the "Evil Empire" rhetoric of the Ronald Reagan administration, Wein and Claremont present their metal-skinned hero as a decent kid. Chris Claremont would later reveal Colossus as a talented painter in his own right, a nice contrast to the character's hulking appearance and job as team muscle, fully rounding-out Marvel's favorite Red. His question to Professor X about whether or not his powers should belong to the state shows Colossus is very much a product of his system, but he's basically good-hearted and kind. Sort of like the submarine crewmembers from Norman Jewison's 1966 comedy The Russians Are Coming, the Russians Are Coming!

Once the regular series starts, Colossus doesn't spend a lot of time trying vainly to re-educate his teammates with Leninist dialectics. Or any at all, if I remember correctly. The only time his politics really come to the forefront is in The Uncanny X-Men #123 and 124 (July and August 1979). During a battle with Arcade a mind-controlled Colossus turns into exactly the kind of stereotype Wein and Claremont so carefully avoided-- the Proletarian. It's a powerful switch, and with it Claremont gives us a satirical taste of the stuff Marvel printed in the 1950s, when Captain America wasn't frozen in ice but actively combating the International Communist Conspiracy and possibly flouridation of water, as well.

Since superhero comic book characters age very slowly (if at all), and because I've long since given up following current continuity, I'm not sure how Marvel handled the Soviet Union's dissolution. The most recent X-Men story I've read-- the Joss Whedon run-- didn't address it at all. Colossus was just there, as apolitical as he'd always been. It seems unlikely a guy like Colossus, who was in his late teens when he first appeared and must only be in his twenties or early thirties now, could possibly have grown up under communist rule on a collective farm. Maybe he's just a simple Siberian farm boy without the political ramifications. Maybe he always was.

No comments:

Post a Comment