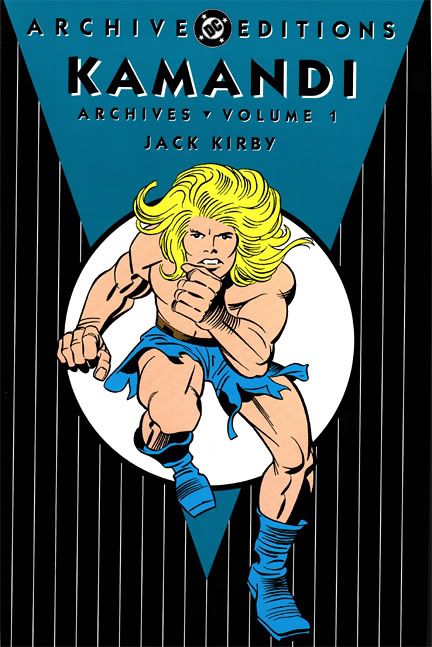

What do you get when you’re DC publisher Carmine Infantino and you float the idea that Jack Kirby should rip off Planet of the Apes? Not a Planet of the Apes rip-off, that’s for sure. If Infantino expected Kirby to content himself with mere talking simians, he was sorely mistaken. And yet that’s pretty much how it happened, and how approximately 65 million years later, we lucky fools ended up with this slick and weighty DC Archives edition of Kamandi.

What do you get when you’re DC publisher Carmine Infantino and you float the idea that Jack Kirby should rip off Planet of the Apes? Not a Planet of the Apes rip-off, that’s for sure. If Infantino expected Kirby to content himself with mere talking simians, he was sorely mistaken. And yet that’s pretty much how it happened, and how approximately 65 million years later, we lucky fools ended up with this slick and weighty DC Archives edition of Kamandi.Or, as I like to call it, Kamandi: The Last Boy on Earth, because that’s the series’ title and I’m clever that way.

Chapter One: The Last Boy on Earth!

Kamandi is a futuristic, roughneck young hippie in a time where barbers have gone extinct, but cut-off denim and motorcycle boots are all the fashion rage. He’s the Charlton Heston surrogate for this madhouse world where not only do gorillas talk and ride horses, but lions and tigers tool around on three-wheelers and radioactive scientists float overhead in helium balloons.

Because it’s Kirby, Kamandi can scarcely contain itself. While he was always possessed of a febrile creativity, as soon as Kirby hit DC, his imagination went into some sort of turbocharged overdrive. His Fourth World stories are over stuffed with incident and new characters, and Kamandi features a similar breathlessly paced narrative. Reading a DC-era Kirby comic like reading ten stories in one.

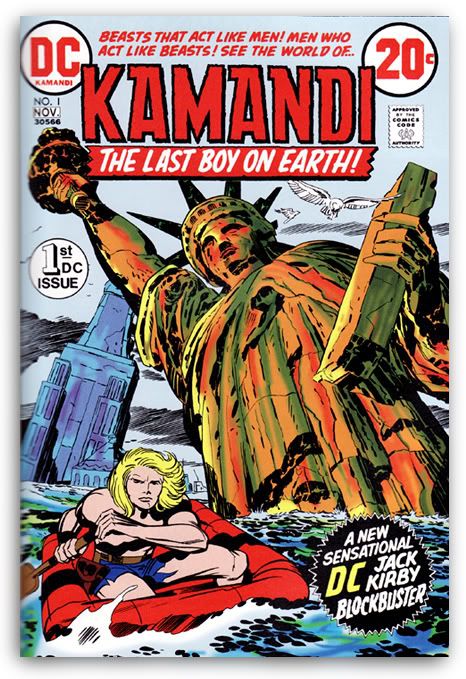

Kirby himself was busy then, too. I believe he was simultaneously producing Jimmy Olsen, Orion, Mr. Miracle and Forever People, spackling his living room wall in preparation for repainting it and mediating the Paris Peace Talks between the United States and the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRVN). And just as he saved our world in reality, Kirby destroys it in the pages of Kamandi. It's the post-apocalypse with a new status quo of underground bunker-dwelling and scavenging for food. Kirby destroys that almost as soon as he introduces it, too. When we first meet Kamandi, he's rafting through a flooded New York with a Statue of Liberty as majestically ruined as the one in the Apes film series, its obvious antecedent. Kirby leads with a splash page followed by a double-page spread no less!

DC... next time you destroy

the Statue of Liberty in a story,

do it the Kirby way.

Six pages in and Kamandi’s guardian/mentor is dead (he barely gets any dialogue), Kamandi’s battling a talking wolf who foolishly beckons, “Here! Give me that gun! --- Come on ---! I won’t hurt’cha!” and then Jolly Jack decides he needs to do something to pick up the pace before reader ennui sets in.

The second sees Kamandi’s new-found radioactive buddy Ben reminding him “Don’t forget Ben Boxer, boy! I’m not like the other humans you’ve seen!” As if Kamandi or the readers could forget- Ben Boxer is a man who has to wear an astronaut suit in order not to kill everyone around him with deadly radiation. Oh, and he turns into steel then deals out ass-whuppin’s. Just like the X-Men's Colossus, only not Russian. And a couple of years earlier.

Then we get yet another double page spread, this time of anthropomorphic rats looting the wreckage of the George Washington Bridge.

Kirby's gorillas are cooler than

the ones from 20th Century Fox.

Just keep Timothy Burton away

from them.

the ones from 20th Century Fox.

Just keep Timothy Burton away

from them.

It’s not until #3 that the Planet of the Apes similarities fully emerge as roughneck gorillas (are there any other kind?) in green hunting caps and purple jumpsuits capture Kamandi. The cover blurbs come backing more hyperbolic bombast than a decade’s worth of today’s comics:

Welcome to a buried Las Vegas! Once a playground for men – now, a sinister hunting ground for gorillas!

So the apocalypse didn’t change much. And then this:

Complete in this issue! “The Thing That Grew on the Moon!”

A thing! And it grew… on the moon! As if the loincloth-sporting gorilla on the cover wasn’t enticement enough. Comics today could use more of this kind of cover copy-- at once hucksterish and tongue-in-cheek, and instantly appealing.

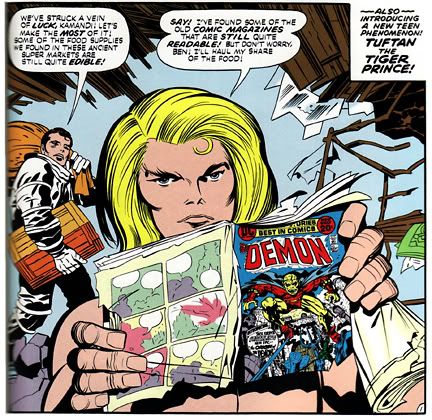

Who says this isn't the Age of

Kirby Self-Promotion? Kirby

works in a little plug for another

of his comics. "Quite readable,"

Kamandi? Quite readable indeed!

I think Kirby may have had bigger plans for Tuftan, the Tiger Prince. He comes on the scene in #4, heralded by a splash page text box labeling him a “new teen phenomenon.” I’m not sure if Kirby means Tuftan is a teenager (and more to the point, a tiger), or that he hopes Tuftan catches on with 70s teens the way David Cassidy and his half-brother Sean did, or Kristy McNichol, or skateboarding, or discotheques or feathered hair. After all, the kids loved Tiger Beat magazine; how could they not love Tiger Prince?

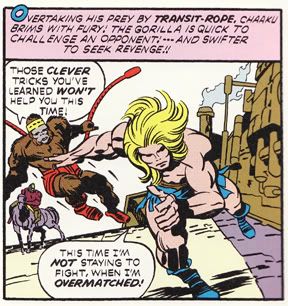

In the post-apocalyptic future,

half-naked neo-hippies will frolic

with headband and loincloth wearing

gorillas on transit ropes!

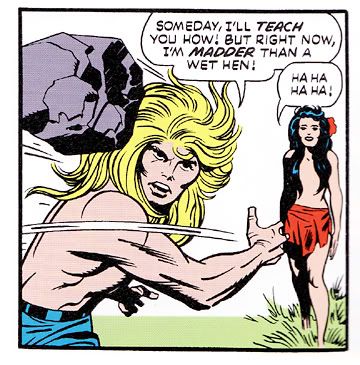

Kamandi and Tuftan get caught between the warring tiger and gorilla armies, and Kamandi gains a talking human girlfriend named Flower… who shamelessly goes around shirtless! Which is only fair, since Kamandi also flaunts bare-chestedness. Flower’s hair gives her some Lady Godiva-style modesty but Kirby’s notion of upper-body nudity is amazingly egalitarian.

In Kirby's future anyone may go

topless without shame! Viva la difference!

topless without shame! Viva la difference!

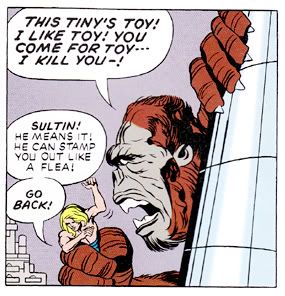

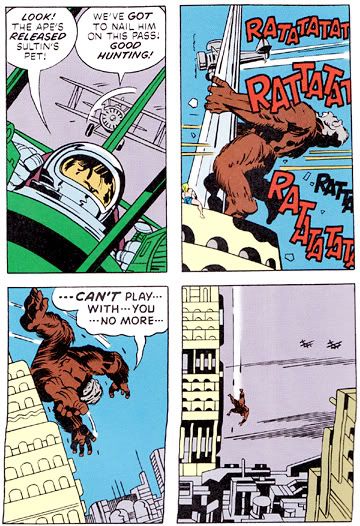

Almost as soon as Kirby establishes the romance between Kamandi and Flower and hints at the eventual reestablishment of some sort of humancentric society, tragedy strikes our young lovers. Kirby examines its aftermath in Kamandi #7, with a chapter intriguingly titled “The United States of Lions." Surprisingly, it has little if anything to do with unions, states and only tangentially features lions. Beginning with a funeral and ending with a skyscraper battle, it's actually Kirby’s parody of King Kong, substituting a massive gorilla; Kong’s equal in stature but superior in conversational skill.

And that’s just a quick overview of the first seven issues! I’m too exhausted to tell you all the details about the last three in this book, in which we visit “Tracking Site,” battle the savage flying bats and the freakish, sinister homunculus who dwells there, intent on unleashing a world-ending bacterium for some obscure reason Kirby can barely take time to explain to us in the breathless rush of his futuristic narrative.

Chapter Two: The Waiting Secret!!

If you haven't guessed by now, Kirby goes pretty far afield, given the series’ original mandate. And while Kirby wasn’t above rehashing classic movie plots he never failed to add twists the original wouldn’t dare. Imagine how insane Beneath the Planet of the Apes would’ve been if, instead of skinless mutants, the gorilla army had encountered talking lions on three-wheelers.

While suffering from an over-reliance on capture, escape and evasion plotting (it becomes repetitive), Kamandi is a sterling example of Kirby’s off-the-wall and unrestrained storytelling, honed over decades of professional work. While he may not have been as interested in the book as he was in his New Gods, the fact remains the man just could not half-ass things even if he tried.

Who else would engineer an entire future Earth, populate it with talking animals of nearly every species, continually hint at a central mystery that unravels intermittently throughout the adventures and introduce brand new characters practically on a page-by-page basis?

From reading these, I can’t help but see Kirby as a mostly intuitive storyteller. Certainly the man was a sponge, soaking in bits of science, legend and myth, and good old Hollywood movies; all of this he'd combine and alter to suit his story needs. Mike Evanier's recollections give me the impression Kirby would frequently come up with a particular direction for a story... then produce something almost totally counter to his original intent. Creating on the fly, always bubbling over with ideas. With that in mind, I don’t see an overall plan here, just incidents piled on incidents.

Groovy incidents. With the intent to entertain the bejeezus out of anyone who buys Kamandi.

And while Kirby may never have written the Great American Novel, it’s probably no accident Kamandi’s adventures take place in the western regions of the former United States. As soon as he departs his underground bunker near New York, Kamandi becomes the classic American pilgrim, sojourning in locales near Las Vegas, Yellowstone Park, even ranging as far as South America in a tip of the hat to Butch Cassidy and his partner in crime, the Sundance Kid.

From James Fenimore Cooper to Mark Twain and Brett Hart, to the relatively more recent Jack Kerouac and Thomas Berger plus many others, American novels frequently explore western migration as related to rugged individualism, which Kamandi certainly personifies. In fact, this is probably the most important defining traits of what we characterize as American literature, at least in the 19th century, and much of the 20th.

The west is the quintessential setting for American literature, with Kamandi the descendant of Huckleberry Finn by way of Col. George Taylor. And like Huck, and Berger’s Jack Crabb, Kamandi rebels against unjust societal expectations, cannot tolerate a life in either literal or figurative captivity. He must remain in motion, forever restless, the personification of our nation in its youth. Unable to relate to most surviving humans, Kamandi remains apart from each culture he encounters. Kirby reinforces this by repeatedly separating Kamandi from Ben Boxer's scientists and having Kamandi assert his human identity and equality to his animal overlords who insist on treating him condescendingly as either a pet, a mascot or an enemy.

As science fiction, technological themes abound in Kamandi, but these are traditionally conflated with western ones in more mainstream American literature as well. While Cooper might bog down the narrative of his 1823 novel The Pioneers to describe a stove in almost Luciferian terms, Kirby, the once and future king of his four-color milieu, creates bizarre flying vehicles and war machines with a gestural whim, yet never slackens the story's pace.

The series has a strange dichotomy-- for humans, advanced technology is of the past, and there’s a nostalgia for what humanity has lost, but along with it, an implied criticism of the queasy, mindless consumerism and complacency that led to this outcome in Kirby’s use of imagery featuring the detritus of a lost civilization: familiar shopping mall signage and weathered sculptures of American presidents (even significantly including one of Richard M. Nixon, never a Kirby favorite) whose identities have been lost to history.

Still, in order to reclaim mastery over the world, which Kamandi sees as a human birthright, he must solve these archaeological mysteries. To this end, Ben Boxer and his scientific comrades are forever seeking the lost “Apollo Project” in an effort to understand this disordered reality.

And while technology is used to destroy (being a Kirby action-fest, violence and weapons-based imagery predominate), there’s also a hopeful quality. If one can defeat the barbarian bat-creatures and the horrific human-created bacterium that can kill all life… one might at the very least, as in "The United States of Lions," find a peaceful place where one might belong.

If, that is, Kamandi can overcome his temper and tendency towards violence. Then again, to Kirby these were also human qualities. To create and destroy, our recurring pattern, even among animals with anthropomorphic qualities. Kamandi lives in a world ruled by violence, both casual and institutionalized- rowdy fistfights, warfare and gladitorial games coexist. Kirby might remind us these, too, are human inventions.

Kirby does Kong. Get Peter

Jackson on the phone! We need

an epic Kamandi movie!

Franklin Schaffner never thought

to put his apes in biplanes, but it

would've been cool if he did. These

are actually lions. Lions in biplanes,

attacking a giant, talking ape who

calls himself Tiny. God, we need

another Jack Kirby.

Chapter Three: The Monster Fetish!

We’re lucky enough of the art exists for DC to gather it all into this hefty and cleanly-designed hardcover. We can enjoy its prime Kirbyness, where his stylistic flourishes, unhindered by the slick ink work from Joe Sinnott at Marvel and the scratchy, unfinished line of Vince Colletta at DC, erupt. Kirby's use of splashes backed by innovative gutter-crossing double spreads on pages 2 and 3 gives the stories a wide-screen feel, opening up the scope and dazzling the reader with Cineramic imagery like a ruined Nevada town, preserved for animal archaeologists by the dry desert air, an Ozymandian image at once humorous and melancholy.

Sic semper Tiny! "Can't play---

with --- you --- no more." He's not

even angry at the lions who killed him.

Isn't that the saddest comic panel ever?

In the Kamandi Archives reprint, the blacks are crisp, the colors smooth. The reconstruction is akin to looking at a restored print of a Cecil B. DeMille epic. These stories were originally printed on grey-toned newsprint which almost immediately began to yellow. And they featured line screens that were practically planet-sized compared to today’s. Now we can see the art on glossy white, with screens so fine they allow the color fields to appear as smooth, flat areas. While this takes away some of the immediacy and ephemeral quality of the originals, it allows us to study the line work unobscured by cheap paper and indifferent printing.

This is especially educational because Mike Royer’s inks always bring out the Kirbyness of Jack Kirby’s pencils. From interviews I’ve read with Royer in the Jack Kirby Collector (a product of the wonderfully nice people at TwoMorrows), it seems his intent was always to preserve the pencils as much as possible. I love this approach, because the attraction of a Kirby comic is its uniqueness. He’s oft-imitated, but no one has ever fully captured the intangibles of the true Kirby.

The most others can do is provide the bombast and overkill, without the humane qualities. Kirby strikes me as having a genuine love for people, be they the shirtless, blonde hippie kid type or the kind hidden in an animal’s fur and sinew.

4 comments:

Have a quick read of "The Last Enemy" from 1957 and any mention of Planet of the Apes in relation to Kamandi becomes superfluous.

(That one picture looks so familiar, though. Where have I seen that before...?)

Great link! Hmm... I think I know the picture you're thinking of, too. But I'm pretty sure I'd remember it if I'd seen it before.

Kamandi is one of those fertile works that soooo transcended the original brief. You're right, Kirby could never do 'half-arsed'.

I'm amazed that we a haven't seen a Kamandi film or TV show. In a time where Hollywood is desperate for ideas, Kamandi is a real treasure trove.

Exactly! So many ideas! Kamandi demands the big-screen treatment.

Post a Comment