Now’s the Time

Mark Evanier, in the closing essay for

Volume 3 of the Kirby’s Fourth World Omnibus, points out the critical reaction

to Kirby’s treatment of Deadman. Kirby, said this critic (I paraphrase),

clearly did not get the Neal Adams Memo. Graceful lines, art school realism,

and noir subtlety “were” the way of “now.” Kirby represented “the past.” Adams

and company represented the future. This is a point of view I would have

heartily, and stupidly, embraced at the time.

“The future” is not a fixed point, however. And even the present is a

bit slippery. My “now” is different from

your “now.” There’s a joke that says, “The golden age of music is 12.” My

golden age of Kirby is 45. This is my “now.”

But Then Was Not

After around a year, the wheels came off

the bus (or super cycle) of the Fourth World. Sales dipped, and books were

canceled. The remarkable achievements that were “The Pact” (New Gods #7) and

“Himon” (Mister Miracle #9) and “The Death Wish of Terrible Turpin” (New Gods

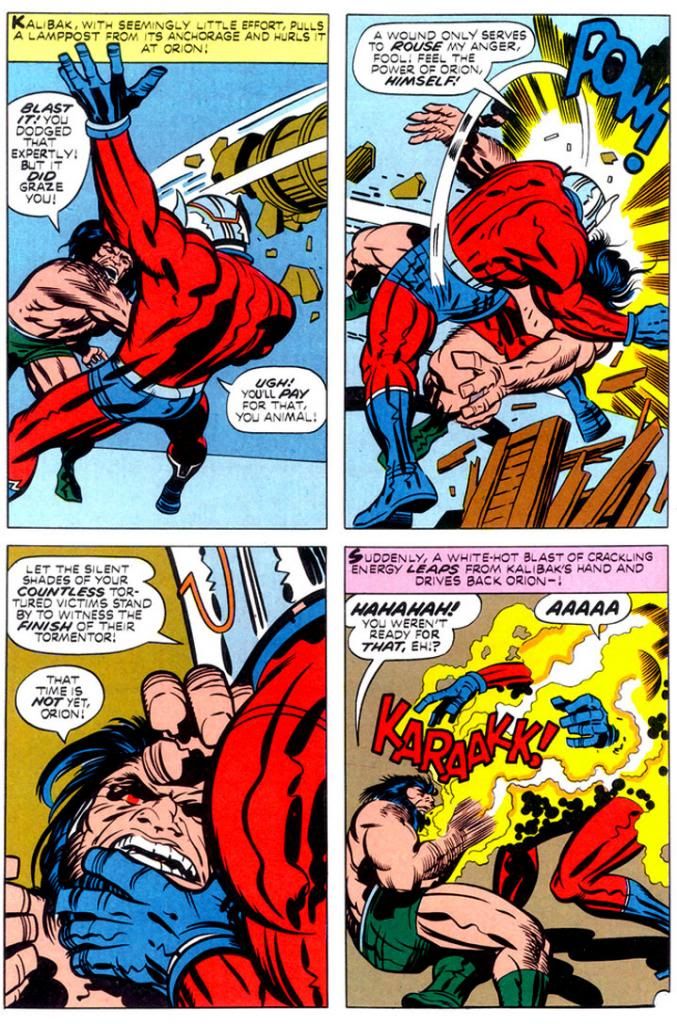

#8) were not seen as masterpieces at the time. The combat between Orion and Kalibak in the

Turpin story will remind you what sort of glory can be found in a slugfest.

But then it ended. The last issue of the

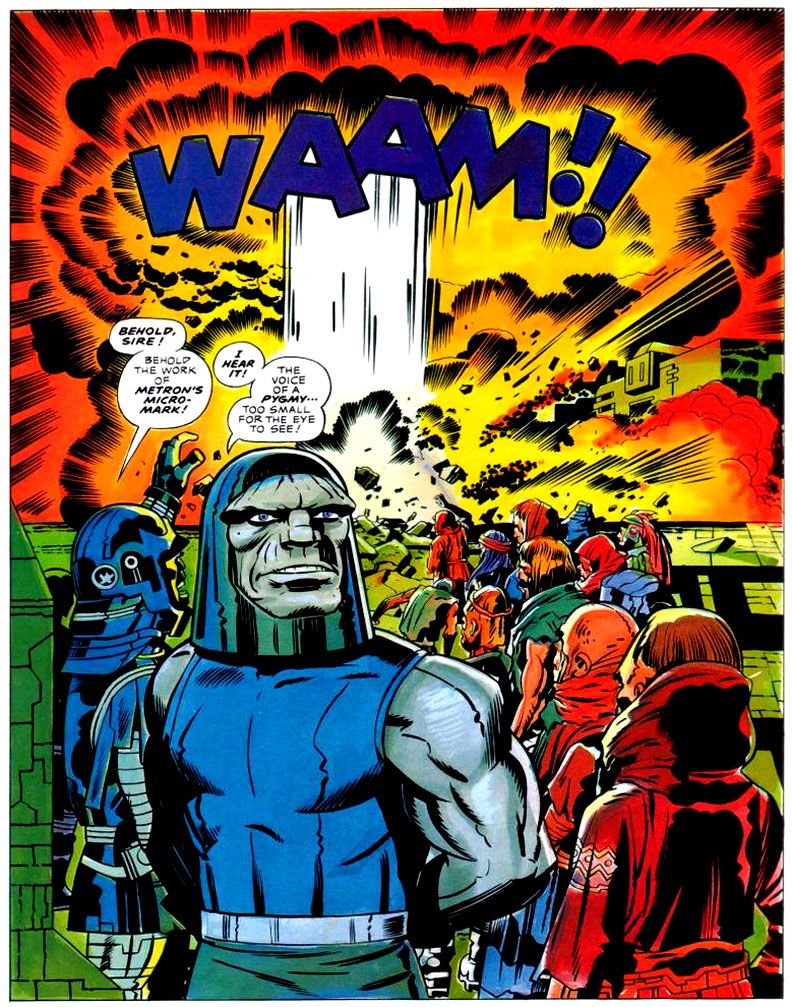

New Gods (“Darkseid and Sons,” #11) was, in fact, brilliant (the run from #7

through the end is worth everyone’s time). The story didn’t end as Kirby wanted

it to, but it was a very effective stopping point with a lot of “What?? What

just happened???” moments. It was very satisfying. The end of the Forever

People was much more of a mess, possibly because their action was always

peripheral to the New Genesis/Apokolips story being told in NG and Miracle. “The Kids” end up stranded on a paradise

planet in a faraway dimension when the Pursuer’s lance blows up, “destroying”

the Infinity Man. While it technically makes sense, the pretext is as weak as

it sounds. |

| New Gods #7, March 1972 (Jack Kirby with inks by Mike Royer) |

Mister Miracle lasts a bit longer than the

other two, but when the Big Story falls away, it becomes a series of one-off

monster stories. This didn’t have to be a problem. Kirby spent the ‘50s being

the master of one-off monster stories.

According to Evanier’s essay, though, Kirby

was feeling demoralized and his heart wasn’t quite in it. You only have to

notice that one of the stories begins with Miracle and Barda stumbling on a “haunted” house while walking in the woods near their house. Yeah, time for a

new direction (which took him to the Demon, Kamandi, et many al., so one can’t

entirely complain). |

| New Gods #8, May 1972 (Jack Kirby with inks by Mike Royer) |

The Problem with Endings

Kirby’s vision from the beginning of the

Fourth World was an enclosed story that reached through a number of books and

ended in a Fourth World Ragnarok, closing the book on these characters for

good. I don’t know how he ever thought that was going to happen.

|

| New Gods #11, November 1972 (Kirby with inks by Mike Royer) |

It seems almost quaint, looking back from

the other side of the graphic novel naissance, but in 1972, DC Comics was not

going to let Kirby develop amazing properties – which is what he was brought in

for – and then have them succumb to irrevocable destruction.

This may have been the one place where

Kirby – a man preternaturally in synch with comic book aesthetic – may have had

an ambition for something that can never exist in the superhero-comic book

medium: an ending. This wasn’t a function of the times Kirby was writing in,

but a function of the medium. Just consider the New Gods. We’ve had The Hunger

Dogs, Kirby’s own imperfect – but beautiful! – attempt at an ending. We’ve had

Death of the New Gods. We’ve had Final Crisis, where Darkseid is “finally”

killed.

Wait, who was that who was featured in the

new Justice League 23.1?

To butcher Fitzgerald, “There are no last

acts in comic book superhero lives.” Even characters who are never brought

back, are constantly being brought up (e.g., Jor-El, Gwen Stacy). I wouldn’t be

the first to suggest that while Crisis of This, That, and the Other Thing had

all the hallmarks of a Ragnarok, they lacked the one key element: the end of the world. They weren’t resetting

the DC universe, they were resetting the DC stylebook.

I think Kirby really wanted the end of the

world for his characters. He had the Wagnerian urge. But like so many great

creators he was an inventor, not a destroyer. He began things. He began great

things. And not a single one of them – not Cap, not the FF, not the New Gods –

has ended. And even if they fall into a space where they seem to have ended –

books get cancelled – there is always a new issue coming down the line. |

| DC Graphic Novel #4: The Hunger Dogs, January 1985 (Kirby with inks by D. Bruce Berry) |

But this is not the problem with endings.

The problem with endings is that our experience of the work is shaped by “how

things turn out.” Forget how things turned out. These are astonishingly rich

stories, executed to a ridiculously high degree; the creation of a visual

aesthetic that’s analogous to Tolkien’s linguistic aesthetic. This will always

be true, no matter how things turn out. Kirby could not achieve his operatic

ambition, but that’s irrelevant. I love these books.

Gary Chapin usually blogs about French accordion music over at www.accordeonaire.blogspot.com.

No comments:

Post a Comment