Coraline

CoralinePublisher: Harper Collins

Adapted and illustrated by P. Craig Russell

Colors: Lovern Kindzierski

Capsule review: P. Craig Russell adapts a Neil Gaiman children's book into a delight for readers of any age. And... it's a hardcover comic published by an actual book publisher! Why aren't there more of these? And more specifically, what do we have to do to get more of these?

When childhood dies, its corpses are called adults and they enter society, one of the politer names of hell.-- Brian Aldiss.

P. Craig Russell visually references Miyazaki Hayao’s masterpiece Tonari no Totoro (That's My Neighbor Totoro to you and me, Russ) in one panel, and Coraline's story is certain reminiscent of that particular animated film. The move to a wondrous new house, nature all wild yet strangely inviting and close at hand, fantastical elements creeping into the sunlight of the banal. But it’s much closer in particulars to Miyazaki’s other great film, Sen to Chihiro no Kamikakushi. And that's Spirited Away to you and me, Russ.

Russ... Russ... your feet...

Like Miyazaki’s Chihiro, Coraline is a girl beset by uncertain circumstances, uneasy with the changes in her life. A new house, a new school, parents who are seemingly becoming self-absorbed as they begin to rely on her growing abilities to look after herself. Parents snatched away to a parallel reality, a distorted version of our own and ruled harshly by a sinister female power, leaving the young protagonist to puzzle it out on her own and save her family.

And the story has all the conventions of all those beloved literary magical children's adventures from Wonderland to Narnia to Terabithia, neatly in place with a few modern flourishes. A plucky lass on the verge of puberty, just brave enough to get herself into trouble and—hopefully—more than clever enough to get herself out. A dangerous well in the overgrown, neglected garden, a bricked-up door to nowhere. Weird, confusing neighbors to mystify and offend our protagonist—is that an echo of T.H White in the crazy old man’s “All the songs I written for the mice to play go oompah oompah. But the white mice will only play toodle oodle, like that?” A hint of Stan Lee in the cat's assertion, "Now, you people have names because you don't know who you are. We know who we are, so we don't need names?"

After all, as the Impossible Man declares to the Fantastic Four, “We Poppupians have no names! We know who we are!”

Once in Other Mother’s power, Coraline has to choose between her former, banal life (with bad cooking and boredom and seldom being the center of attention) or a new life as Other Mother’s beloved and obedient daughter (with delicious food, all the crazy costumes she could ever hope to wear and freaky black rats to play with). Other Mother’s offer comes with a price; first, Coraline must give up her eyes in favor of shiny black buttons and second, Other Mother’s love leads to a living death over time. Our real families can appear neglectful at times, especially to the self-centeredness of youth; that kind of love is frequently dull but seldom fatal.

Eventually, Coraline competes with Other Mother in a game to free herself, her parents and the lost souls of Other Mother's previous child-victims. It involves the strange logic of dreams and certain loopholes Coraline must overcome with smarts and growing wisdom. And such is Coraline's metaphorical take on the process of growing up.

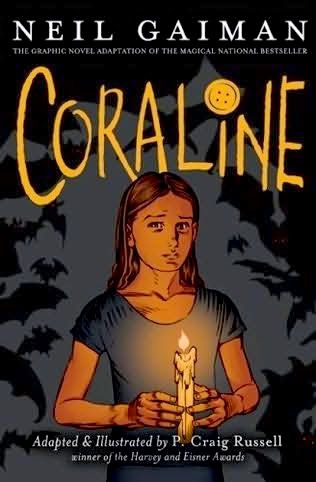

I have no idea how faithfully Russell has adapted the original novel, because I haven’t read it. To be honest, I’ve hardly read anything of Neil Gaiman’s. But I am a Miyazaki fan, and the little hint of his influence here, along with Russell’s art—of which I’m an avid collector—and the hardcover book format attracted me to Coraline. I’m sure the publicity surrounding the animated film version didn’t hurt, either. And it’s a beautiful effort, from the choice of hardcover in a kind of schoolbook finish, to the mysterious cover (Coraline with candle, surrounded by bats, evoking a Halloween mood)

Which brings me to one other point. If there's anything that bothers me about Coraline, it’s that imaginative works like this rely on just that—the reader’s imagination. Things described in prose can reveal themselves in amorphous yet clear-enough form in the mind’s eye. The film adaptation goes for a creepy, Tim Burton-esque aesthetic, all stylized weirdness and cartoony figures with giant heads and pointy noses. That, to me, matches the abstraction of personal imagination and complements it, rather than replaces it.

Russell’s art, however, makes the strangeness a bit too concrete, a bit too literal. Other Mother also has a disconcerting resemblance to Tea Leoni. Despite her button eyes, evil smirk and blood-red claws, she really doesn’t come across as either attractive enough to temp Coraline, or repulsively dangerous enough to really darken the book’s delicate sensibilities or become a truly menacing presence to the girl until nearly the very end.

Either your sensibilities and Russell's visual specificities jibe or not, but once you see his versions of the characters, settings and some of the magical events, they're apt to replace yours. So be prepared.

Still, Coraline is a lovely book to look at and read. The finely-balanced prose finds its match in Russell's ornate lines, and Lovern Kindzierski's rich coloring (gorgeous use of neutrals, nothing garish or over-modeled). Russell can seemingly draw anything, from nearly photo-realistic characters (I wonder how much he relies on photo-reference or if he just makes this stuff up all out of his head... I imagine it's a combination of both) to lush, overgrown gardens to fabulous dreamscapes tinged with mist and mystery.

I really wish comics in general would move towards this format, and more publishers would take chances on literary, self-contained works like Coraline. Between this and the very different Skim, we're starting to see the growing potential of Western sequentials freed from serialization and genre limitations.

No comments:

Post a Comment