I think it's pretty obvious Alex Toth loved drawing stories about aviation. After all, that was the hook of his best-known Batman tale, "Death Flies the Haunted Skies" (Detective Comics #442) and also of his Bravo for Adventure series-- which needs a reprinting, somebody, anywhere! For someone as important to the development of American comic book art as Toth, examples of his work can be frustratingly difficult to find.

That's why I'm eternally thankful to Image for publishing Zorro, Dark Horse for doing those Creepy and Eerie archive books and Fantagraphics for their gorgeous Blazing Combat volume. While the Zorro book is a bargain-- roughly 248 pages of prime Toth for under 15 bucks at Amazon-- culling his stories from hardcover artsy books means collecting Toth can be financially draining but spiritually uplifting, if you're that into the finest in sequential illustration. Which I am.

While there are a few books about Toth due out this year, I want big, fat trade paperback black and white reprints of everything he did in his career all in one place, or two or three. What I'm saying is... DC definitely needs to do a Toth book or two with all the western, romance, superhero, science fiction and horror stories he did for them. And we need more of his Gold Key work, mostly movie or TV adaptations like Darby O'Gill and the Little People, The Land Unknown, 77 Sunset Strip, The Wings of Eagles and... The Danny Thomas Show.

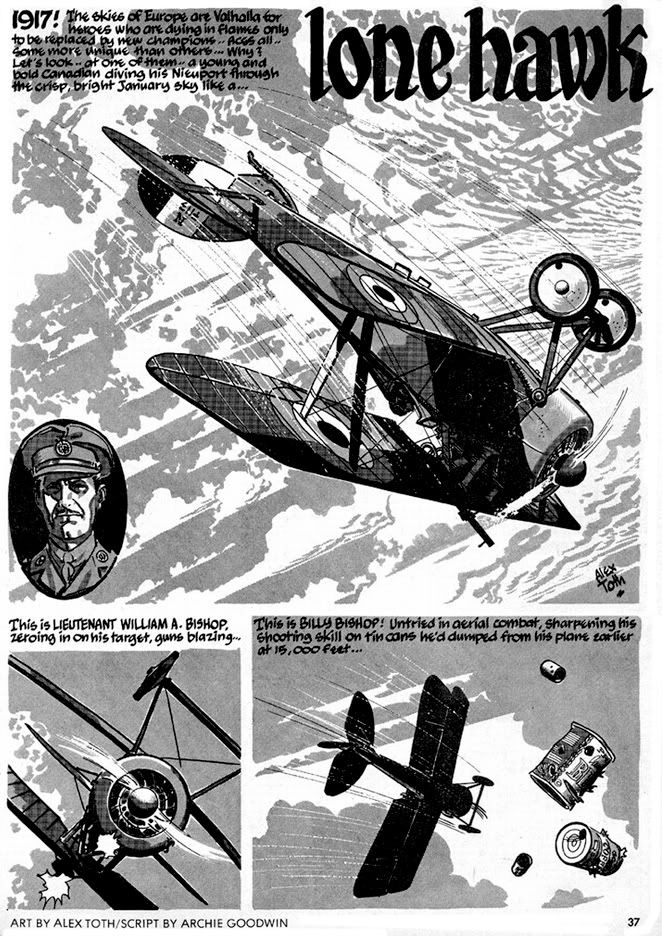

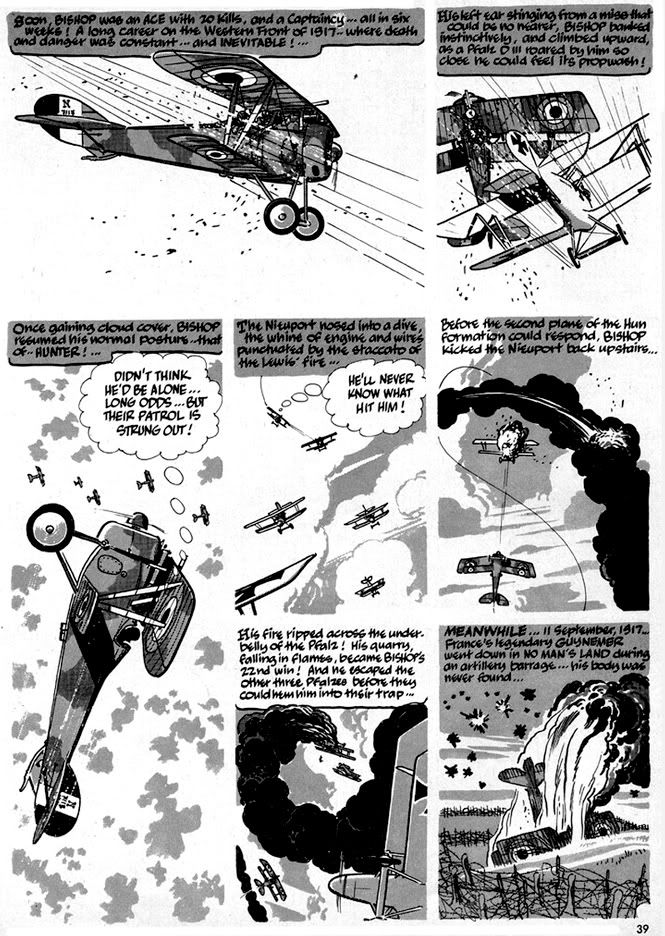

Anyway, airplanes. Toth and airplanes. That's what we're here to talk about today. Here's Toth drawing WWI flying action from Warren's Blazing Combat #2. It's "Lone Hawk," the non-fiction story of top Canadian ace Billy Bishop. Bishop downed 72 enemy aircraft (planes and balloons), making him the Allies' third highest scorer. Archie Goodwin's script plays to Toth's love affair with all things winged and powered by starting in the sky and staying there for the most part. Toth gets to draw all kinds of primitive fighters/scouts while Goodwin contrasts Bishop's victories with the deaths of other top aces such as France's Georges Guynemer and Germany's Manfred von Richthofen.

It's a powerful script showing that the price of martial glory is usually horrific death. Prose and art come together to hammer home this point in a singularly effective panel where Goodwin's caption introduces us to American Raoul Lufbery (French-American, actually) as he leaps without a parachute from his burning plane. That's how terrified even these ostensibly fearless men were of burning to death. Toth's art depicts the plane as a streaking fireball and Lufbery as a tiny, fragile figure falling away from it to his doom.

For this story, Toth uses what appears to be Craftint doubletone paper for his grays rather than washes. These planes flew and fought at relatively low altitudes, so there are masses of clouds made up of a single tone framing them and the panels themselves-- Toth eschews panel outlines. The mechanical look of the Craftint halftones gives the work a kind of antiqued, etching-like quality. All this with just two values of gray, plus black and white. And, of course, the visual storytelling is superb. Each action is clearly delineated and the aerial sequences are dramatic and dynamic but easy to follow and understand. Toth is in his element.

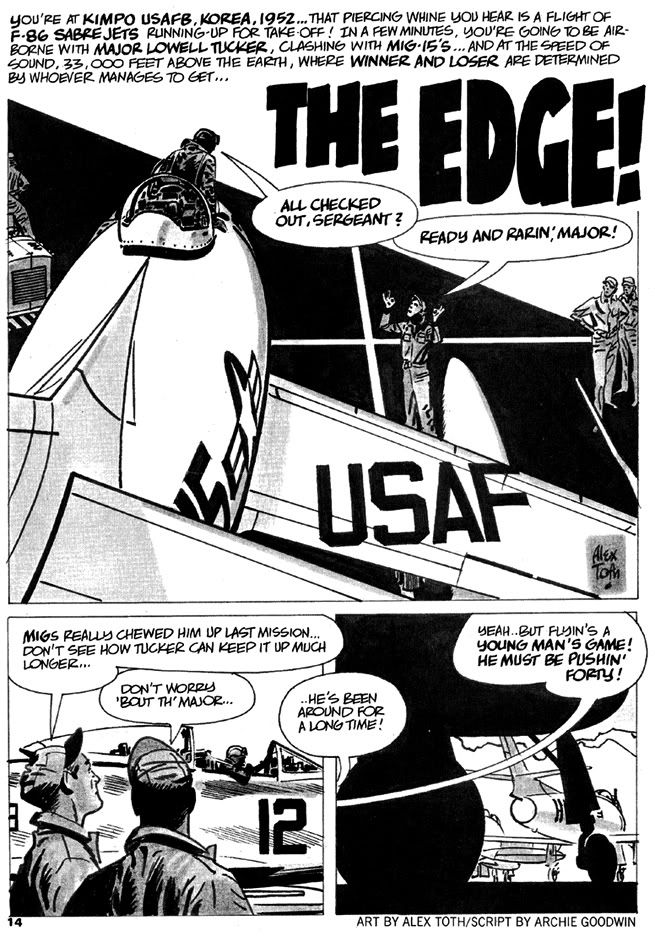

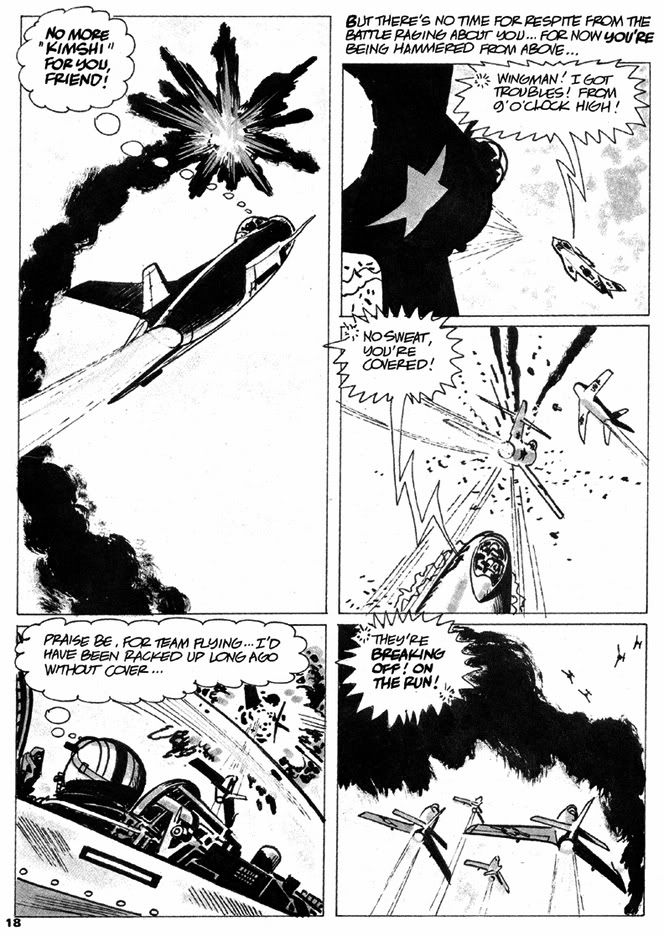

Flash forward a couple of generations and these creaking box-kite fighters have been replaced by streaking metal jets. This time Goodwin and Toth take us to the skies over the Korean peninsula. Planes now swirl around in deadly spirals in a cloudless, high altitude realm of startlingly bright sunlight, so Toth uses ruling lines to separate panels. But within these his work becomes almost abstract. F-86 Sabers and MiG-15s don't offer as much surface detail as the Sopwith Camels and Fokker Triplanes of the Great War. The fighter jet is like a steel knife in the sky, sleek and speedy with simpler lines. A quick stab and it's all over for you, as this North Korean fighter jock soon learns:

"No more 'kimshi' for you, friend!"? Hey, how do you even know that guy liked kimchi, you stereotyping jerk? Maybe he was allergic. No more kimchi for you, my friend, or taco salad or cheeseburgers for that matter! No more anything because BLAM!

Billy Bishop's primitive acrobatics over mud have evolved into the cold precision of high-tech, near-supersonic murder so Toth adjusts his art accordingly with a more contemporary approach borrowing elements from fine art. He reduces the planes and their cockpits to geometry, silhouettes surrounded by speedlines and stark white backdrops. Even the few landscapes seem abstracted to mere designs. The effect is thoroughly modern, plastic and alloy rather than wood and canvas and bereft of any lingering sense of romance. The human element, so stunningly depicted in the burning plane panel of "Lone Hawks" is almost completely absent here. We don't even see a frontal view of a face until the final panel.

I have to wonder if Toth's approach here doesn't also evince a distaste for this era. Goodwin could easily have written into his script this de-emphasis on the human element. Visually, both "Lone Hawks" and "The Edge" focus on the machines of war. I'm not about to count it up, but both more than likely feature the same number of panels devoted to airplanes. But Goodwin in the former repeatedly personalizes the various aces' deaths even if Toth doesn't draw the men all that often. The latter draws you in with that second person narration, but Toth's art keeps you effectively outside with its sleekness and finally presents you with a face that so obviously isn't your own.

I feel the WWI aerial combat and its purer contesting of man against man plus all that "knights of the air" chivalric stuff would appeal to Toth's sensibilities more so than the push-button nature of the Korean War version. Perhaps it's just Toth taking into account the differing eras, but while I admire the technical aspects of "The Edge" in a dispassionate way, I'm moved by "Lone Hawk."

There's a tension between words and pictures in "The Edge," though, that I can't leave alone. Perhaps it's also the result of an ambivalence on Archie Goodwin's part, as well. Goodwin's second-person narration isn't exactly pro-war, but it is more in the "our boys are the good guys doing a dirty but necessary job" mode rather than the more empathetic "death takes us all indiscriminately" feel of "Lone Hawk." Addressed as "you," the reader gets to be the protagonist, seemingly admired by both the writer and the ground crew characters for his prowess and hard-won expertise. Yet we know little of the enemy other than they're part of the collective horde of Communist aggressors and therefore less than human. Lessons learned fighting the Nazis must be applied against this new threat as well. Goodwin seems to suggest with this comparison while we might deplore having to kill, sometimes we must to thwart greater evils.

Or something like that. The American pilot is little more than a cipher himself. What personal details we learn about him are completely in service to the story's final gag. It's kind of an odd note to strike in the context of Blazing Combat (given its reputation) and seems a better fit as back-up in one of DC's slightly more jingoistic war books. Our Army at War, maybe.

Two creators taking on two different wars.

No comments:

Post a Comment